Questões de Vestibular

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 4.863 questões

Fonte: New York Times. Publicado em 10/10/2017. Disponível em: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/10/ opinion/giving-capitalism-a-social-conscience.html . Acesso em 06/11/2017. [Excerpt]

Storyline

This film recounts the history and attitudes of the opposing sides of the Vietnam War using archival news footage as well as its own film and interviews. A key theme is how attitudes of American racism and self-righteous militarism helped create and prolong this bloody conflict. The film also endeavors to give voice to the Vietnamese people themselves as to how the war has affected them and their reasons why they fight the United States and other western powers while showing the basic humanity of the people that US propaganda tried to dismiss. Written by Kenneth Chisholm

Source: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0071604/accessed on October 10, 2015

According to the storyline above, the film Hearts & Minds:

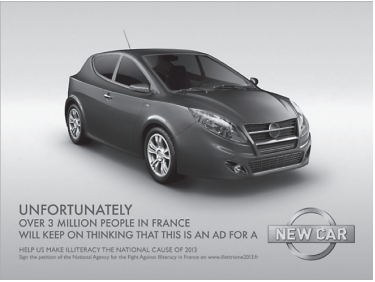

(Source: http://www.adweek.com/news-gallery/advertising-branding/ worlds-best-print-ads-2012-13-150758#gold-lion-anlci-1-of-6-42)

“The master of the house, reminding himself of the twofold necessity of sporadically engaging in sport and of getting the family some lunch, appeared resplendent in a pair of swimming trunks and resolved to follow the path traced by the chicken: in cautious leaps and bounds, he scaled the roof where the chicken, hesitant and tremulous, urgently decided on another route. The chase now intensified. From roof to roof, more than a block along the road was covered. Little accustomed to such a savage struggle for survival, the chicken had to decide for herself the paths she must follow without any assistance from her race. The man, however, was a natural hunter. And no matter how abject the prey, the cry of victory was in the air.”

According to the text, the father:

Read the following passage of “The Dinner”, by Clarice Lispector, and answer question.

“I leaned over my meal, lost. When I finally managed to confront him from the depths of my pallid face, I observed that he, too, was leaning forward, his elbows resting on the table, his head between his hands. And obviously he could bear it no longer. His bushy eyebrows were touching. His food must have lodged just below his throat under the stress of his emotion, for when he was able to continue, he made a visible effort to swallow, dabbing his forehead with his napkin. I could bear it no longer, the meat on my plate was raw… and I really could not bear it another minute. But he – he was eating.

The waiter brought a bottle in a bucket of ice. I noted every detail without being capable of discrimination. The bottle was different, the waiter in tails, and the light haloed the robust head of Pluto which was now moving with curiosity, greedy and attentive. For a second the waiter obliterated my view of the elderly gentleman and I could only see his black coattails hovering over the table as he poured red wine into the glass and waited with ardent eyes – because here was a surely man who would tip generously, one of those elderly gentlemen who still command attention… and power. The elderly gentleman, who now seemed larger, confidently took a sip, lowered his glass, and sourly considered the taste in his mouth. He compressed his lips and smacked them with distaste, as if the good were also intolerable. I waited, the waiter waited, and we both leaned forward in suspense. Finally he made a grimace of approval. The waiter curved his shiny head in submission to the man’s words of thanks and went off with lowered head, while I sighed with relief.

He now mingled gulps of wine with the meat in his great mouth and his false teeth

ponderously chewed while I observed him… in vain. Nothing more happened. The

restaurant appeared to radiate with renewed intensity under the tinkling of glass and

cutlery; in the brightly lit dome of the room the whispered conversation rose and fell

in gentle waves; the woman in the large hat smiled with half closed eyes, looking

slender and beautiful as the waiter carefully poured the wine into her glass. But now

he was making another gesture.”