Questões de Concurso

Comentadas sobre aspectos linguísticos | linguistic aspects em inglês

Foram encontradas 616 questões

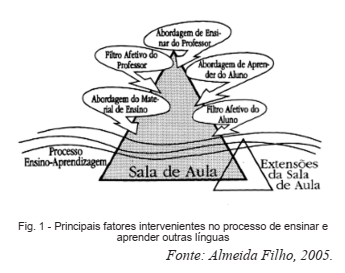

Almeida Filho (2005) illustrates in figure 1:

Read the excerpt from TOMLINSON (2011) “Ideally language learners should have strong and consistent motivation and they should also have positive feelings towards the target language, their teachers, their fellow learners and the materials they are using. But, of course, ideal learners do not exist and even if they did exist one day, they would no longer be ideal learners the next day. Each class of learners using the same materials will differ from each other in terms of long- and short-term motivation and of feelings and attitudes about the language, their teachers, their fellow learners and their learning materials, and of attitudes towards the language, the teacher and the materials. Obviously no materials developer can cater for all these affective variables, but it is important for anybody who is writing learning materials to be aware of the inevitable attitudinal differences of the users of the materials.”

What can be concluded from the text about

materials to teach languages is that their developers

should take into account that:

“Language techniques are designed to engage learners in the pragmatic, authentic, functional use of language for meaningful purposes. Organizational language forms are not the central focus, but rather aspects of language that enable the learner to accomplish these purposes.” (BROWN, 2007).

The previous statement is a reference to:

TEXT I

Critical Literacy, EFL and Citizenship

We believe that a sense of active citizenship needs to be developed and schools have an important role in the process. If we agree that language is discourse, and that it is in discourse that we construct our meanings, then we may perceive the foreign language classrooms in our schools as an ideal space for discussing the procedures for ascribing meanings to the world. In a foreign language we learn different interpretive procedures, different ways to understand the world. If our foreign language teaching happens in a critical literacy perspective, then we also learn that such different ways to interpret reality are legitimized and valued according to socially and historically constructed criteria that can be collectively reproduced and accepted or questioned and changed. Hence our view of the EFL classroom, at least in Brazil, as an ideal space for the development of citizenship: the EFL classrooms can adopt a critical discursive view of reality that helps students see claims to truth as arbitrary, and power as a transitory force which, although being always present, is also in permanent change, in a movement that constantly allows for radical transformation. The EFL classroom can thus raise students’ perception of their role in the transformation of society, once it might provide them with a space where they are able to challenge their own views, to question where different perspectives (including those allegedly present in the texts) come from and where they lead to. By questioning their assumptions and those perceived in the texts, and in doing so also broadening their views, we claim students will be able to see themselves as critical subjects, capable of acting upon the world.

[…]

We believe that there is nothing wrong with using the mother tongue in the foreign language classroom, since strictly speaking, the mother tongue is also foreign - it’s not “mine”, but “my mother’s”: it was therefore foreign as I first learned it and while I was learning to use its interpretive procedures. When using critical literacy in the teaching of foreign languages we assume that a great part of the discussions proposed in the FL class may happen in the mother tongue. Such discussions will bring meaning to the classroom, moving away from the notion that only simple ideas can be dealt with in the FL lesson because of the students’ lack of proficiency to produce deeper meanings and thoughts in the FL. Since the stress involved in trying to understand a foreign language is eased, students will be able to bring their “real” world to their English lessons and, by so doing, discussions in the mother tongue will help students learn English as a social practice of meaning-making.

(Source: Adapted from JORDÃO, C. M. & FOGAÇA, F. C. Critical Literacy in

The English Language Classroom. DELTA, vol. 28, no 1, São Paulo, p. 69-84,

2012. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/delta/v28n1a04.pdf).

TEXT I

Critical Literacy, EFL and Citizenship

We believe that a sense of active citizenship needs to be developed and schools have an important role in the process. If we agree that language is discourse, and that it is in discourse that we construct our meanings, then we may perceive the foreign language classrooms in our schools as an ideal space for discussing the procedures for ascribing meanings to the world. In a foreign language we learn different interpretive procedures, different ways to understand the world. If our foreign language teaching happens in a critical literacy perspective, then we also learn that such different ways to interpret reality are legitimized and valued according to socially and historically constructed criteria that can be collectively reproduced and accepted or questioned and changed. Hence our view of the EFL classroom, at least in Brazil, as an ideal space for the development of citizenship: the EFL classrooms can adopt a critical discursive view of reality that helps students see claims to truth as arbitrary, and power as a transitory force which, although being always present, is also in permanent change, in a movement that constantly allows for radical transformation. The EFL classroom can thus raise students’ perception of their role in the transformation of society, once it might provide them with a space where they are able to challenge their own views, to question where different perspectives (including those allegedly present in the texts) come from and where they lead to. By questioning their assumptions and those perceived in the texts, and in doing so also broadening their views, we claim students will be able to see themselves as critical subjects, capable of acting upon the world.

[…]

We believe that there is nothing wrong with using the mother tongue in the foreign language classroom, since strictly speaking, the mother tongue is also foreign - it’s not “mine”, but “my mother’s”: it was therefore foreign as I first learned it and while I was learning to use its interpretive procedures. When using critical literacy in the teaching of foreign languages we assume that a great part of the discussions proposed in the FL class may happen in the mother tongue. Such discussions will bring meaning to the classroom, moving away from the notion that only simple ideas can be dealt with in the FL lesson because of the students’ lack of proficiency to produce deeper meanings and thoughts in the FL. Since the stress involved in trying to understand a foreign language is eased, students will be able to bring their “real” world to their English lessons and, by so doing, discussions in the mother tongue will help students learn English as a social practice of meaning-making.

(Source: Adapted from JORDÃO, C. M. & FOGAÇA, F. C. Critical Literacy in

The English Language Classroom. DELTA, vol. 28, no 1, São Paulo, p. 69-84,

2012. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/delta/v28n1a04.pdf).

Based on the text, judge the following items.

The final “s” in “ideas” (line 2) and “brains” (line 8) is pronounced in the same way.

Based on the text, judge the following items.

Based on the text, judge the following item.

Based on the text, judge the following item.

The “ed” ending in “produced” (line 2) is pronounced differently from the “ed” ending in “performed” (line 6).

Based on the text, judge the following item.

Based on the text, judge the following item.

The use of the hyphen in “well‐documented” (line 5) is optional.

Based on the text, judge the following item.

The word though can be used instead of “even though” (line 2) without affecting the meaning of the sentence.

Still in practical terms, focusing on lexical terms may be a challenge for the teacher and the student. Penny Ur (2012, p. 69) alerts teachers to the importance of revising vocabulary instead of testing students on it so as to “consolidate and deepen students’ basic knowledge”. It’s important to focus the revision on single-items as well as items in context, using a wide range of exercises, which means, for example:

I conducting dictations.

II having students brainstorm in groups.

III doing a quick bingo.

IV composing stories together.

V finding collocations on websites or dictionaries.

The alternative that best matches the exercises

suggested above with their target language is: