Questões de Concurso

Sobre uso dos adjetivos | use of adjectives em inglês

Foram encontradas 97 questões

Milly: “I'm from East Grinstead in West Sussex - probably about 50 minutes south of London. | guess it's kind of a country town, so a lot different from the busy capital. My hometown is quite green and nice. | like it. You go down the high street and everyone tends to know one another. It's homely and safe.”

Adapted from htips://www.bbc.com/Aleamingenglish

All adjectives below were used by Milly to describe her hometown, EXCEPT for:

TEXT 2

WHAT IS THE COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH?

In the Communicative Approach, real communication and interaction is not only the objective in learning, but also the means through which it takes place. This approach started in the 70s and became prominent as it proposed an alternative to the then ubiquitous systems-oriented approaches, such as the Audiolingual method. That means that, instead of focusing on the acquisition of grammar and vocabulary (grammatical/linguistic competence), the Communicative Approach aimed at developing the learner’s competence to communicate in the target language (communicative competence), with an enhanced focus on real-life situations.

Excerpt extracted and adapted from: https://www.whatiselt.com/single-post/2018/08/23/what-is-thecommunicative-approach

Answer the question based on the following text.

(Available at: https://www.onlygoodnewsdaily.com/post/woven-city-toyota-s-real-world-test-bed-for-futuretech – text specially adapted for this test).

Read the lyrics carefully and answer the following questions:

Like a Rolling Stone (Bob Dylan)

Read the lyrics carefully and answer the following questions:

The Times They Are A-Changin' (Bob Dylan)

O texto seguinte servirá de base para responder à questão.

India's luxury airline Vistara flies into the sunset

Indian full-service carrier Vistara will operate its last flight on Monday, after nine years in existence.

A joint venture between Singapore Airlines and the Tata Sons, Vistara will merge with Tata-owned Air India to form a single entity with an expanded network and broader fleet.

This means that all Vistara operations will be transferred to and managed by Air India, including helpdesk kiosks and ticketing offices. The process of migrating passengers with existing Vistara bookings and loyalty programmes to Air India has been under way over the past few months.

"As part of the merger process, meals, service ware and other soft elements have been upgraded and incorporates aspects of both Vistara and Air India," an Air India spokesperson said in an email response.

Amid concerns that the merger could impact service standards, the Tatas have assured that Vistara's in-flight experience will remain unchanged.

Known for its high ratings in food, service, and cabin quality, Vistara has built a loyal customer base and the decision to retire the Vistara brand has been criticised by fans, branding experts, and aviation analysts.

The consolidation was effectively done to clean up Vistara's books and wipe out its losses, said Mark Martin, an aviation analyst.

Air India has essentially been "suckered into taking a loss-making airline" in a desperate move, he added.

"Mergers are meant to make airlines powerful. Never to wipe out losses or cover them."

To be sure, both Air India and Vistara's annual losses have reduced by more than half over the past year, and other operating metrics have improved too. But the merger process so far has been turbulent.

The exercise has been riddled with problems − from pilot shortages that have led to massive flight cancellations, to Vistara crew going on mass sick leave over plans to align their salary structures with Air India.

There have also been repeated complaints about poor service standards on Air India, including viral videos of broken seats and non-functioning inflight entertainment systems.

The Tatas have announced a $400m (£308m) programme to upgrade and retrofit the interiors of its older aircraft and also a brand-new livery. They've also placed orders for hundreds of new Airbus and Boeing planes worth billions of dollars to augment their offering.

But this "turnaround" is still incomplete and riddled with problems, according to Mr Martin. A merger only complicates matters.

Experts say that the merger strikes a dissonant chord from a branding perspective too.

Harish Bijoor, a brand strategy specialist, told the BBC he was feeling "emotional" that a superior product offering like Vistara which had developed a "gold standard for Indian aviation" was ceasing operations.

"It is a big loss for the industry," said Mr Bijoor, adding it will be a monumental task for the mother brand Air India to simply "copy, paste and exceed" the high standards set by Vistara, given that it's a much smaller airline that's being gobbled up by a much larger one.

Mr Bijoor suggests a better strategy would have been to operate Air India separately for five years, focusing on improving service standards, while maintaining Vistara as a distinct brand with Air India prefixed to it.

"This would have given Air India the time and chance to rectify the mother brand and bring it up to the Vistara level, while maintaining its uniqueness," he adds.

Beyond branding, the merged entity will face a slew of operational challenges.

"Communication will be a major challenge in the early days, with customers arriving at the airport expecting Vistara flights, only to find Air India branding," says Ajay Awtaney, editor of Live From A Lounge, an aviation portal. "Air India will need to maintain clear communication for weeks."

Another key challenge, he notes, is cultural: Vistara's agile employees may struggle to adjust to Air India's complex bureaucracy and systems.

But the biggest task for the merged carrier would be offering customers a uniform flying experience.

These are "two airlines with very different service formats are being integrated into one airline. It is going to be a hotchpotch of service formats, cabin formats, branding, and customer experience. It will involve learning and unlearning, and such a process has rarely worked with airlines and is seldom effective," said Mr Martin.

Still, many believe Vistara had to go − now or some years later.

A legacy brand like Air India, with strong global recognition and 'India' imprinted in its identity, wouldn't have allowed a smaller, more premium subsidiary to overshadow its revival process.

Financially too, it makes little sense for the Tatas to have two loss-making entities compete with one another.

The combined strength of Vistara and Air India could also place the Tatas in a much better position to compete with market leader Indigo.

The unified Air India group (including Air India Express, which completed its merger with the former Air Asia India in October) "will be bigger and better with a fleet size of nearly 300 aircraft, an expanded network and a stronger workforce", an Air India spokesperson said.

"Getting done with the merger means that Air India grows overnight, and the two teams start cooperating instead of competing. There will never be one right day to merge. Somewhere, a line had to be drawn," said Mr Awtaney.

But for many Vistara loyalists, its demise leaves a void in India's skies for a premium, full-service carrier - marking the third such gap after the collapse of Kingfisher Airlines and Jet Airways.

It's still too early to say if Air India, which often ranks at the bottom of airline surveys, can successfully fill that void.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5ygp1w5eq7o

Running is a refreshingly uncomplicated way to get your heart pumping. You can do it nearly anywhere, and you don’t need much to make it happen (other than the motivation to go). That said, functional gear that speaks to your specific needs can enhance your experience. We’ve spent hundreds of hours researching and testing, enlisting the help of a collegiate track coach (and former podiatrist), a former Runner’s World editor, and several of the most passionate runners on our staff. Here are our recommendations for the best gear to get you up and running.

Disponível em: https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/reviews/the-best-running-gear/.

Adjectives, both common and demonstrative, serve to modify nouns, providing additional description or details. They improve the clarity and specificity of language, allowing speakers to convey precise images or ideas. Therefore, select the alternative that correctly uses common and demonstrative adjectives.

Read Text I and answer question.

Text I: The speed of sound

Some music fans now know 15-second sped up snippets of songs better than the real thing. It’s thanks to an emerging trend on social media, particularly TikTok, of creators changing the tempo of popular songs by 25-30%, to accompany short viral videos of dances or other themes. This phenomenon presents a very modern challenge – how can singers create the next hit tune when the one people actually listen to might sound so different?

Sped-up listening emerged in the early 2000s as “Nightcore”, launched by a Norwegian DJ duo of the same name, who sped up a song’s pitch and speed. This is now commonplace on social media apps, where the speed of podcasts, voice notes, movies and more can be increased so that people can consume them in less time. But what people might not know is that unofficial sped-up or slowed down tunes are different to a professional remix because they are far shorter and can be easily made by anyone, including on TikTok, Instagram Reels and other apps.

In 2023, more than a third of Spotify listeners in the US sped up podcasts and nearly two-thirds played songs at a quicker tempo. The streaming service recently confirmed to the BBC that it was testing a new and more widespread feature that could potentially allow its customers to remix the tempo of songs and share them. In addition, some popstars are embracing this phenomenon. In November 2022, for example, fan-made sped-up versions of RAYE’s single “Escapism” helped the artist to achieve her first ever number one on the UK Official Singles Chart, nearly three months after its original release. Furthermore, Billie Eilish has also released official fast and slow versions of songs and Sabrina Carpenter’s hits “Please Please Please” and “Espresso” received similar treatment.

Dr Mary Beth Ray, an author focused on digital music culture, says short-form video platforms like TikTok “constrain our ways of listening into snippets, but those constraints also let you experience a track in a new way”. She also said that “short clips provide a quicker line to that dopamine rush social media wants us to feel – so there is an addictive element which we’re pushed towards.”

BBC Radio 1 DJ Maia Beth feels it's now getting hard for established labels and musicians to ignore this trend because it can sometimes feel like if they don't release the sped up version, then someone else will. Beth, who admits she can't imagine sitting and listening to a sped-up version of a song the whole way through, believes the trend shouldn't necessarily be a major distraction for musicians though. “Sped-up versions of tracks can help artists break through or go viral, although that initial success may not last,” she added.

TikTok says it has noticed an increase in the number of sped-up and slowed down versions of catalogue tracks taken off the platform, then become officially released. These official changed-tempo releases are now grouped together with the original song in the UK Official Singles Chart, along with remixes, acoustic and live versions, helping artists to climb the ranks.

That said, not everyone is happy with the trend. The popularity of speed-altered versions can make it harder to distinguish original from remix while altering an artist's intended pacing, mood and tone. However, while some artists like them and others less so, it seems they are here to stay.

Adapted from: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cqv5x2qe8q6o Published: August 17, 2024

“It’s thanks to an emerging trend on social media, particularly TikTok, of creators changing the tempo of popular songs by 25-30%, to accompany short viral videos of dances or other themes.”

Instruction: answer the question based on the following text.

HBO posts casting call for next-generation Harry Potter TV series

By Vivian Ho

(Available at: www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/sep/10/hbo-posts-casting-call-for-nextgeneration-harry-potter-tv-series – text especially adapted for this test)

In the third sentence of the text, “supreme” is an adjective modifying the noun “perfection”.

Text II

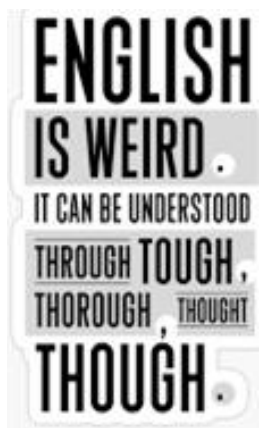

From: https://images.app.goo.gl/dCFurjmcnZzU7AHS6

Regarding the sentence

“It’s no wonder that you don’t support their ideas; after all, their lack of knowledge is utterly conspicuous”

it is CORRECT to affirm that: