Questões de Concurso Público Prefeitura de Jacaraú - PB 2020 para Professor de Inglês

Foram encontradas 15 questões

TEXT I-

ENEM and the Language Policy forEnglish in the Brazilian Context

Andrea Barros Carvalho de Oliveira

1.INTRODUCTION

In the present article, I report the results of a doctoral research that focused on the language policy for English in Brazil, considering specifically the role of Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (hereinafter ENEM) in this policy. Thus, taking into account the sociopolitical aspects of the teaching processes, learning, and use of English as a foreign language, we sought to identify the possible impact of ENEM on the status of English language as a school subject.

ENEM was initially conceived as a final exam to evaluate students at the end of basic education. However, it has been modified over the last few years to work as an entrance examination for public and private universities. In addition, the use of this exam in several governmental programs aimed at higher education access was preponderant to make it a high stakes exam in the educational scenario.

According to the literature on language examination exams, especially those considered to be high stakes, are seen as an intrinsically political activity (ALDERSON; BANERJEE, 2001). These exams can be used as educational policy tools as well as to promote a specific language related to local language policy objectives.

The theoretical conception of Language Policy (hereinafter LP) adopted in this investigation refers to Shohamy (2006). This author postulates that, although there is an official LP established in legislation and official documents, it is also necessary to consider the existence of a “real” LP, or “de facto” LP, which is put into practice through mechanisms, resources such as traffic signs, rules and laws related to official bodies, language exams, among others. Besides mechanisms, the beliefs or representations about the language that are shared in the community ought to be considered as well. The importance of mechanisms is that they reveal the true aims of LPas established by the government for a specific language, which are not always explicit in Brazilian law.

The research, the results of which are presented in this article, covered the three components of Shohamy’s theoretical model, namely: legislation, mechanisms (in this case, an exam, ENEM), and representations or beliefs about language. To obtain a sample of representations about English language, interviews were conducted with the students from an ENEM preparatory course for university entrance, with two teachers of English and two coordinators from public schools.

In the present article, I begin with a review of the expanded conception of LPelaborated by Shohamy, as it is the theoretical basis of this research. Second, I analyze some documents and laws regarding English teaching in Brazil. In addition to these documents, the English questions of ENEM (2016) were taken in consideration. Finally, I present an overview of the representations about English language that emerged from the interviews which constituted the empirical data of my doctoral thesis.

ALDERSON, J. C; BANERJEE, J. Language Testing and Assessment. Language Testing, [S.l.], n. 34, 2001, p. 213-236.

SHOHAMY, E. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. (Adapted from: OLIVEIRA, A.B.C. ENEM and the Language Policy for English in the Brazilian Context. In.: Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. vol.19 no.2 th Belo Horizonte Apr./June 2019 Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-63982019000200361 Accessed on October 20 , 2019)

TEXT I-

ENEM and the Language Policy forEnglish in the Brazilian Context

Andrea Barros Carvalho de Oliveira

1.INTRODUCTION

In the present article, I report the results of a doctoral research that focused on the language policy for English in Brazil, considering specifically the role of Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (hereinafter ENEM) in this policy. Thus, taking into account the sociopolitical aspects of the teaching processes, learning, and use of English as a foreign language, we sought to identify the possible impact of ENEM on the status of English language as a school subject.

ENEM was initially conceived as a final exam to evaluate students at the end of basic education. However, it has been modified over the last few years to work as an entrance examination for public and private universities. In addition, the use of this exam in several governmental programs aimed at higher education access was preponderant to make it a high stakes exam in the educational scenario.

According to the literature on language examination exams, especially those considered to be high stakes, are seen as an intrinsically political activity (ALDERSON; BANERJEE, 2001). These exams can be used as educational policy tools as well as to promote a specific language related to local language policy objectives.

The theoretical conception of Language Policy (hereinafter LP) adopted in this investigation refers to Shohamy (2006). This author postulates that, although there is an official LP established in legislation and official documents, it is also necessary to consider the existence of a “real” LP, or “de facto” LP, which is put into practice through mechanisms, resources such as traffic signs, rules and laws related to official bodies, language exams, among others. Besides mechanisms, the beliefs or representations about the language that are shared in the community ought to be considered as well. The importance of mechanisms is that they reveal the true aims of LPas established by the government for a specific language, which are not always explicit in Brazilian law.

The research, the results of which are presented in this article, covered the three components of Shohamy’s theoretical model, namely: legislation, mechanisms (in this case, an exam, ENEM), and representations or beliefs about language. To obtain a sample of representations about English language, interviews were conducted with the students from an ENEM preparatory course for university entrance, with two teachers of English and two coordinators from public schools.

In the present article, I begin with a review of the expanded conception of LPelaborated by Shohamy, as it is the theoretical basis of this research. Second, I analyze some documents and laws regarding English teaching in Brazil. In addition to these documents, the English questions of ENEM (2016) were taken in consideration. Finally, I present an overview of the representations about English language that emerged from the interviews which constituted the empirical data of my doctoral thesis.

ALDERSON, J. C; BANERJEE, J. Language Testing and Assessment. Language Testing, [S.l.], n. 34, 2001, p. 213-236.

SHOHAMY, E. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. (Adapted from: OLIVEIRA, A.B.C. ENEM and the Language Policy for English in the Brazilian Context. In.: Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. vol.19 no.2 th Belo Horizonte Apr./June 2019 Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-63982019000200361 Accessed on October 20 , 2019)

TEXT I-

ENEM and the Language Policy forEnglish in the Brazilian Context

Andrea Barros Carvalho de Oliveira

1.INTRODUCTION

In the present article, I report the results of a doctoral research that focused on the language policy for English in Brazil, considering specifically the role of Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (hereinafter ENEM) in this policy. Thus, taking into account the sociopolitical aspects of the teaching processes, learning, and use of English as a foreign language, we sought to identify the possible impact of ENEM on the status of English language as a school subject.

ENEM was initially conceived as a final exam to evaluate students at the end of basic education. However, it has been modified over the last few years to work as an entrance examination for public and private universities. In addition, the use of this exam in several governmental programs aimed at higher education access was preponderant to make it a high stakes exam in the educational scenario.

According to the literature on language examination exams, especially those considered to be high stakes, are seen as an intrinsically political activity (ALDERSON; BANERJEE, 2001). These exams can be used as educational policy tools as well as to promote a specific language related to local language policy objectives.

The theoretical conception of Language Policy (hereinafter LP) adopted in this investigation refers to Shohamy (2006). This author postulates that, although there is an official LP established in legislation and official documents, it is also necessary to consider the existence of a “real” LP, or “de facto” LP, which is put into practice through mechanisms, resources such as traffic signs, rules and laws related to official bodies, language exams, among others. Besides mechanisms, the beliefs or representations about the language that are shared in the community ought to be considered as well. The importance of mechanisms is that they reveal the true aims of LPas established by the government for a specific language, which are not always explicit in Brazilian law.

The research, the results of which are presented in this article, covered the three components of Shohamy’s theoretical model, namely: legislation, mechanisms (in this case, an exam, ENEM), and representations or beliefs about language. To obtain a sample of representations about English language, interviews were conducted with the students from an ENEM preparatory course for university entrance, with two teachers of English and two coordinators from public schools.

In the present article, I begin with a review of the expanded conception of LPelaborated by Shohamy, as it is the theoretical basis of this research. Second, I analyze some documents and laws regarding English teaching in Brazil. In addition to these documents, the English questions of ENEM (2016) were taken in consideration. Finally, I present an overview of the representations about English language that emerged from the interviews which constituted the empirical data of my doctoral thesis.

ALDERSON, J. C; BANERJEE, J. Language Testing and Assessment. Language Testing, [S.l.], n. 34, 2001, p. 213-236.

SHOHAMY, E. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. (Adapted from: OLIVEIRA, A.B.C. ENEM and the Language Policy for English in the Brazilian Context. In.: Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. vol.19 no.2 th Belo Horizonte Apr./June 2019 Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-63982019000200361 Accessed on October 20 , 2019)

TEXT I-

ENEM and the Language Policy forEnglish in the Brazilian Context

Andrea Barros Carvalho de Oliveira

1.INTRODUCTION

In the present article, I report the results of a doctoral research that focused on the language policy for English in Brazil, considering specifically the role of Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (hereinafter ENEM) in this policy. Thus, taking into account the sociopolitical aspects of the teaching processes, learning, and use of English as a foreign language, we sought to identify the possible impact of ENEM on the status of English language as a school subject.

ENEM was initially conceived as a final exam to evaluate students at the end of basic education. However, it has been modified over the last few years to work as an entrance examination for public and private universities. In addition, the use of this exam in several governmental programs aimed at higher education access was preponderant to make it a high stakes exam in the educational scenario.

According to the literature on language examination exams, especially those considered to be high stakes, are seen as an intrinsically political activity (ALDERSON; BANERJEE, 2001). These exams can be used as educational policy tools as well as to promote a specific language related to local language policy objectives.

The theoretical conception of Language Policy (hereinafter LP) adopted in this investigation refers to Shohamy (2006). This author postulates that, although there is an official LP established in legislation and official documents, it is also necessary to consider the existence of a “real” LP, or “de facto” LP, which is put into practice through mechanisms, resources such as traffic signs, rules and laws related to official bodies, language exams, among others. Besides mechanisms, the beliefs or representations about the language that are shared in the community ought to be considered as well. The importance of mechanisms is that they reveal the true aims of LPas established by the government for a specific language, which are not always explicit in Brazilian law.

The research, the results of which are presented in this article, covered the three components of Shohamy’s theoretical model, namely: legislation, mechanisms (in this case, an exam, ENEM), and representations or beliefs about language. To obtain a sample of representations about English language, interviews were conducted with the students from an ENEM preparatory course for university entrance, with two teachers of English and two coordinators from public schools.

In the present article, I begin with a review of the expanded conception of LPelaborated by Shohamy, as it is the theoretical basis of this research. Second, I analyze some documents and laws regarding English teaching in Brazil. In addition to these documents, the English questions of ENEM (2016) were taken in consideration. Finally, I present an overview of the representations about English language that emerged from the interviews which constituted the empirical data of my doctoral thesis.

ALDERSON, J. C; BANERJEE, J. Language Testing and Assessment. Language Testing, [S.l.], n. 34, 2001, p. 213-236.

SHOHAMY, E. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. (Adapted from: OLIVEIRA, A.B.C. ENEM and the Language Policy for English in the Brazilian Context. In.: Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. vol.19 no.2 th Belo Horizonte Apr./June 2019 Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-63982019000200361 Accessed on October 20 , 2019)

TEXT II

Another Brick In The Wall (Pink Floyd)

We don't need no education

We don't need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers, leave them kids alone

Hey! Teacher! Leave them kids alone!

All in all, it's just another brick in the wall

All in all, you're just another brick in the wall

(Adapted from: https://www.letras.mus.br/pink-floyd/64541/. Accessed on October 31 , 2019).

TEXT II

Another Brick In The Wall (Pink Floyd)

We don't need no education

We don't need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers, leave them kids alone

Hey! Teacher! Leave them kids alone!

All in all, it's just another brick in the wall

All in all, you're just another brick in the wall

(Adapted from: https://www.letras.mus.br/pink-floyd/64541/. Accessed on October 31 , 2019).

TEXT II

Another Brick In The Wall (Pink Floyd)

We don't need no education

We don't need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers, leave them kids alone

Hey! Teacher! Leave them kids alone!

All in all, it's just another brick in the wall

All in all, you're just another brick in the wall

(Adapted from: https://www.letras.mus.br/pink-floyd/64541/. Accessed on October 31 , 2019).

TEXT III

(Available at: https://www.glasbergen.com/gallery-search/?tag=learning. Accessed on October 26 , 2019)

TEXT III

(Available at: https://www.glasbergen.com/gallery-search/?tag=learning. Accessed on October 26 , 2019)

TEXT III

(Available at: https://www.glasbergen.com/gallery-search/?tag=learning. Accessed on October 26 , 2019)

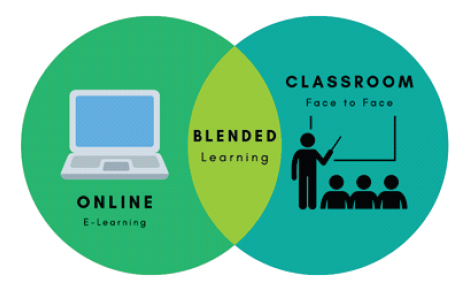

TEXT IV

(Available at: https://www.teachthought.com/learning/what-is-competency-based-learning/ Accessed on October 22 , 2019).

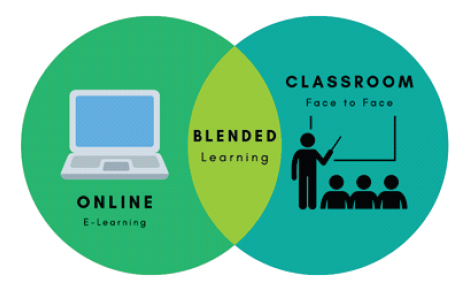

TEXT IV

(Available at: https://www.teachthought.com/learning/what-is-competency-based-learning/ Accessed on October 22 , 2019).

What is blended learning and how does it work?

What is blended learning and how does it work?

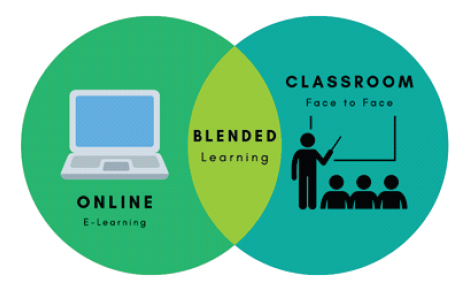

What is blended learning and how does it work?