Questões de Concurso Público BANESE 2012 para Técnico Bancário, Informática - Suporte

Foram encontradas 70 questões

Use It Better: The Smart Ways to Pick Passwords

Four strategies for keeping your information safe

By David Pogue, September 7, 2011

If you want to be absolutely secure, you should make up a different password for every single Web site you visit. Each password should have at least 16 characters, and it should contain a scramble of letters, numbers, and punctuation; it should contain no recognizable words. You should change all of these passwords every couple of weeks. And you should not write any of them down anywhere.

That, at least, is what security experts advise. Unfortunately, they leave out the part about the 15 minutes you’d have to spend with flash cards before bed each night, trying to remember all those utterly impractical passwords.

There are, fortunately, more sensible ways to incorporate passwords into your life. You won’t be as secure as the security experts would like, but you’ll find a much better balance between protection and convenience.

♦ The “security through brevity” technique. My teenage son’s smartphone password is only a single character. It’s fast and easy to type. But a random evildoer picking up his phone doesn’t know that; he just sees “Enter password” and gives up − so, in its way, it’s just as secure as a long password. (Of course, I may have just blown it by publishing his little secret.)

♦ Password keepers. The world is full of utility programs for your Mac, PC or app phone that memorize all your Web passwords for you. They’re called things like RoboForm, Account Logon, and (for the Mac) 1Password. Each asks you for a master password that unlocks all the others; after that, you get to surf the Web freely, admiring how the software not only remembers your passwords and contact information, but fills in the Web forms for you automatically.

♦ The “disguised English word” technique. Having your passwords guessed by ne’er-do-wells online doesn’t happen often, but you do hear about such cases. The bad guys start by using “dictionary attacks” − software that tries every word in the dictionary, just in case you were dumb enough to make your password something like “password” or your first name. (These special dictionaries also contain common names, places, number combinations and phrases such as “ilovemycat.”)

That’s why conventional wisdom suggests disguising your password by changing a letter or two into numbers or symbols. Instead of “supergirl,” choose “supergir!” or “supergir1,” for example. That way, you’ve thwarted the dictionary attacks without decreasing the memorizability.

♦ The multi-word approach. Another good password technique is to run words together, like “picklenose” or “toothygrin.” Pretty easy to remember, but tough for a dictionary attack to guess.

(Adapted from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=pogue-use-it-better-smart-ways-pick-passwords)

Use It Better: The Smart Ways to Pick Passwords

Four strategies for keeping your information safe

By David Pogue, September 7, 2011

If you want to be absolutely secure, you should make up a different password for every single Web site you visit. Each password should have at least 16 characters, and it should contain a scramble of letters, numbers, and punctuation; it should contain no recognizable words. You should change all of these passwords every couple of weeks. And you should not write any of them down anywhere.

That, at least, is what security experts advise. Unfortunately, they leave out the part about the 15 minutes you’d have to spend with flash cards before bed each night, trying to remember all those utterly impractical passwords.

There are, fortunately, more sensible ways to incorporate passwords into your life. You won’t be as secure as the security experts would like, but you’ll find a much better balance between protection and convenience.

♦ The “security through brevity” technique. My teenage son’s smartphone password is only a single character. It’s fast and easy to type. But a random evildoer picking up his phone doesn’t know that; he just sees “Enter password” and gives up − so, in its way, it’s just as secure as a long password. (Of course, I may have just blown it by publishing his little secret.)

♦ Password keepers. The world is full of utility programs for your Mac, PC or app phone that memorize all your Web passwords for you. They’re called things like RoboForm, Account Logon, and (for the Mac) 1Password. Each asks you for a master password that unlocks all the others; after that, you get to surf the Web freely, admiring how the software not only remembers your passwords and contact information, but fills in the Web forms for you automatically.

♦ The “disguised English word” technique. Having your passwords guessed by ne’er-do-wells online doesn’t happen often, but you do hear about such cases. The bad guys start by using “dictionary attacks” − software that tries every word in the dictionary, just in case you were dumb enough to make your password something like “password” or your first name. (These special dictionaries also contain common names, places, number combinations and phrases such as “ilovemycat.”)

That’s why conventional wisdom suggests disguising your password by changing a letter or two into numbers or symbols. Instead of “supergirl,” choose “supergir!” or “supergir1,” for example. That way, you’ve thwarted the dictionary attacks without decreasing the memorizability.

♦ The multi-word approach. Another good password technique is to run words together, like “picklenose” or “toothygrin.” Pretty easy to remember, but tough for a dictionary attack to guess.

(Adapted from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=pogue-use-it-better-smart-ways-pick-passwords)

Use It Better: The Smart Ways to Pick Passwords

Four strategies for keeping your information safe

By David Pogue, September 7, 2011

If you want to be absolutely secure, you should make up a different password for every single Web site you visit. Each password should have at least 16 characters, and it should contain a scramble of letters, numbers, and punctuation; it should contain no recognizable words. You should change all of these passwords every couple of weeks. And you should not write any of them down anywhere.

That, at least, is what security experts advise. Unfortunately, they leave out the part about the 15 minutes you’d have to spend with flash cards before bed each night, trying to remember all those utterly impractical passwords.

There are, fortunately, more sensible ways to incorporate passwords into your life. You won’t be as secure as the security experts would like, but you’ll find a much better balance between protection and convenience.

♦ The “security through brevity” technique. My teenage son’s smartphone password is only a single character. It’s fast and easy to type. But a random evildoer picking up his phone doesn’t know that; he just sees “Enter password” and gives up − so, in its way, it’s just as secure as a long password. (Of course, I may have just blown it by publishing his little secret.)

♦ Password keepers. The world is full of utility programs for your Mac, PC or app phone that memorize all your Web passwords for you. They’re called things like RoboForm, Account Logon, and (for the Mac) 1Password. Each asks you for a master password that unlocks all the others; after that, you get to surf the Web freely, admiring how the software not only remembers your passwords and contact information, but fills in the Web forms for you automatically.

♦ The “disguised English word” technique. Having your passwords guessed by ne’er-do-wells online doesn’t happen often, but you do hear about such cases. The bad guys start by using “dictionary attacks” − software that tries every word in the dictionary, just in case you were dumb enough to make your password something like “password” or your first name. (These special dictionaries also contain common names, places, number combinations and phrases such as “ilovemycat.”)

That’s why conventional wisdom suggests disguising your password by changing a letter or two into numbers or symbols. Instead of “supergirl,” choose “supergir!” or “supergir1,” for example. That way, you’ve thwarted the dictionary attacks without decreasing the memorizability.

♦ The multi-word approach. Another good password technique is to run words together, like “picklenose” or “toothygrin.” Pretty easy to remember, but tough for a dictionary attack to guess.

(Adapted from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=pogue-use-it-better-smart-ways-pick-passwords)

Considere o problema abaixo.

“Márcio escolheu um número racional e somou o dobro do seu quadrado com sua terça parte. Do resultado encontrado, subtraiu a soma de 21,08 com o quádruplo desse número. Ao final do cálculo, Márcio obteve N como resposta. Qual foi o número escolhido por Márcio?”

Para que 5,7 seja uma das possíveis respostas desse problema, o valor de N deve ser

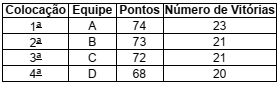

A tabela a seguir mostra a situação dos quatro primeiros colocados em um campeonato de futebol faltando uma rodada para o seu término.

Na última rodada, acontecerão os seguintes jogos:

Equipe A x Equipe B Equipe C x Equipe D

O campeão será o time que tiver conquistado o maior número de pontos no campeonato. Em caso de empate nesse critério, o campeão é aquele com o maior número de vitórias. Em cada jogo, uma equipe ganha 3 pontos em caso de vitória, 1 ponto em caso de empate e 0 ponto em caso de derrota. Em relação às chances de cada equipe sagrar-se campeã, considere as afirmativas abaixo.

I. Se a equipe A vencer ou empatar sua partida, será a campeã. Caso contrário, não leva o título.

II. Se a equipe B vencer sua partida, será a campeã. Caso contrário, não leva o título.

III. Se a equipe C vencer sua partida e as equipes A e B empatarem seu jogo, C será a campeã. Caso contrário, não leva o título.

Está correto o que se afirma em

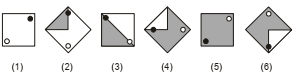

Observe a sequência de figuras.

Considerando o padrão definido pelas seis primeiras figuras da sequência, a figura (7) será