Questões de Concurso Público TRT - 9ª REGIÃO (PR) 2013 para Analista Judiciário - Tecnologia da Informação

Foram encontradas 60 questões

I. Simplificam a implantação registrando certificados de usuários e computadores sem a intervenção do usuário.

II. Aumentam a segurança de acesso com melhor segurança do que as soluções de nome de usuário e senha, e a capacidade de verificar a validade de certificados usando o Protocolo de Status de Certificados Online (OCSP).

III. Simplificam o gerenciamento de certificados e cartões inteligentes por meio da integração com o Forefront Identity Manager.

As descrições acima são referentes ao

- por meio do comprometimento do servidor de DNS do provedor que você utiliza;

- pela ação de códigos maliciosos projetados para alterar o comportamento do serviço de DNS do seu computador;

- pela ação direta de um invasor, que venha a ter acesso às configurações do serviço de DNS do seu computador ou modem de banda larga.

Este tipo de fraude é chamado de

I. Visa governar os investimentos em gerenciamento de serviços através da empresa e gerenciá-los para que adicionem valor ao negócio. Este processo estabelece que há duas categorias de serviço: os serviços de negócio (definidos pelo próprio negócio) e os serviços de TI (fornecidos pela TI ao negócio, mas que este não reconhece como dentro de seus domínios).

II. Visa manter e melhorar a qualidade dos serviços de TI através de um ciclo contínuo de atividades, envolvendo planejamento, coordenação, elaboração, estabelecimento de acordo de metas de desempenho e responsabilidade mútuas, monitoramento e divulgação de níveis de serviço (em relação aos clientes), de níveis operacionais (em relação a fornecedores internos) e de contratos de apoio com fornecedores de serviços externos.

III. Abrange o gerenciamento do tratamento de um conjunto de mudanças em um serviço de TI, devidamente autorizadas (incluindo atividades de planejamento, desenho, construção, configuração e teste dos itens de software e hardware), visando criar um conjunto de componentes finais e implantá-los em bloco em um ambiente de produção, de forma a adicionar valor ao cliente, em conformidade com os requisitos estabelecidos na estratégia e no desenho do serviço.

A relação correta entre a descrição do processo e o nome do processo e da publicação que o contém é

Algumas das práticas e características desses modelos de processo são descritas a seguir:

I. Programação em pares, ou seja, a implementação do código é feita em dupla.

II. Desenvolvimento dividido em ciclos iterativos de até 30 dias chamados de sprints.

III. Faz uso do teste de unidades como sua tática de testes primária.

IV. A atividade de levantamento de requisitos conduz à criação de um conjunto de histórias de usuários.

V. O ciclo de vida é baseado em três fases: pre-game phase, game-phase, post-game phase.

VI. Tem como único artefato de projeto os cartões CRC.

VII. Realiza reuniões diárias de acompanhamento de aproximadamente 15 minutos.

VIII. Define seis marcos durante o projeto e a implementação de uma funcionalidade: walkthroughs do projeto, projeto, inspeção do projeto, codificação, inspeção de código e progressão para construção.

IX. Os requisitos são descritos em um documento chamado backlog e são ordenados por prioridade.

A relação correta entre o modelo de processo ágil e a prática/característica é:

Para uma empresa atingir o nível de maturidade 2 (Gerenciado) é preciso desenvolver áreas de alguns processos, dentre eles,

Exemplo 1: for (int indice=0; indice<clientes.size();indice++) { Cliente cli = (Cliente) clientes.get(indice); out.println(cli.getNomCli()); }

Exemplo 2:

Iterator it = clientes.iterator();

while (it.hasNext()) {

Cliente cli = (Cliente) it.next();

out.println(cli.getNomCli());

}

Exemplo 3:

for (Object objeto_cliente:clientes) {

Cliente cli = (Cliente) objeto_cliente;

out.println(cli.getNomCli());

}

É correto afirmar que:

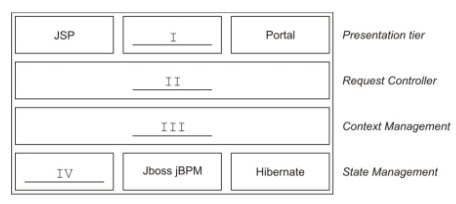

As lacunas I, II, III e IV são preenchidas, correta e, respectivamente, por

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">

<title>Teste</title>

<style type="text/css">

table.formato_tabela tr td:not(:last-child) {background: #0f0;}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<table class="formato_tabela" border="1">

<tr>

<td>Célula 1.1</td>

<td>Célula 1.2</td>

<td>Célula 1.3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Célula 2.1</td>

<td>Célula 2.2</td>

<td>Célula 2.3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Célula 3.1</td>

<td>Célula 3.2</td>

<td>Célula 3.3</td>

</tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>

A instrução CSS no interior da tag

If It’s for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man’s

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

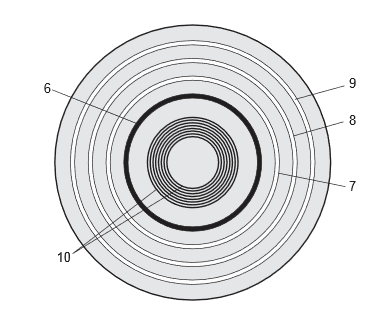

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I’m going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale,” Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn’t know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: ‘Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.’ ”

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later,” Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle.”

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

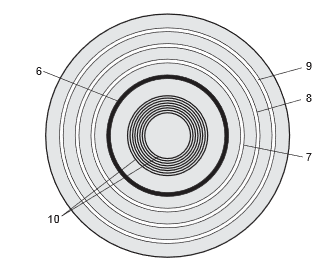

But that method − a variegated bull’s-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland’s considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-joseph-woodland-inventor-of-the-bar-code-dies-at-91.html?nl=todaysheadlines

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

O pronome “It”, no início do texto, refere-se a

If It’s for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man’s

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I’m going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale,” Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn’t know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: ‘Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.’ ”

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later,” Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle.”

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull’s-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland’s considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-joseph-woodland-inventor-of-the-bar-code-dies-at-91.html?nl=todaysheadlines

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

A ideia de Woodland e Silver foi patenteada em

If It's for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man's

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I'm going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale," Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn't know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: 'Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.' "

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later," Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle."

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull's-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland's considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-josep...

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

Infere-se do texto que

If It’s for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man’s

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I’m going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale,” Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn’t know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: ‘Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.’ ”

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later,” Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle.”

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull’s-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland’s considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-joseph-woodland-inventor-of-the-bar-code-dies-at-91.html?nl=todaysheadlines

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

Dentro do contexto, a tradução correta para o significado de “it languished for years” é

If It's for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man's

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I'm going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale," Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn't know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: 'Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.' "

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later," Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle."

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull's-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland's considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-josep...

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

De acordo com o texto,