Questões de Concurso Público Prefeitura de Lavras - MG 2022 para Professor Médio Língua Inglesa

Foram encontradas 10 questões

Why can group work be a challenge in monolingual classes?

[1] Firstly, and most obviously, the lack of a need to communicate in English means that any communication between learners in that language will seem artificial and arguably even unnecessary. Secondly, the fact that all the learners in the class share a common culture (and are often all from the same age group) will mean that there will often be a lack of curiosity about what other class members do or think, thus making questionnaire-based activities superfluous. Thirdly, there is the paradox that the more interesting and motivating the activity is (and particularly if it involves a competitive element of some sort), the more likely the learners are to use their mother tongue in order to complete the task successfully or to finish first. Finally, the very fact that more effort is involved to communicate in a foreign language when the same task may be performed with much less effort in the mother tongue will also tend to ensure that very little English is used.

Is group work worth the effort?

[2] Taken as a whole, these factors will probably convince many teachers that it is simply not worth bothering with pair and group work in monolingual classes. This, however, would be to exclude from one’s teaching a whole range of potentially motivating and useful activities and to deny learners the opportunity to communicate in English in class time with anyone but the teacher.

[3] Simple mathematics will tell us that in a one-hour lesson with 20 learners, each learner will speak for just 90 seconds if the teacher speaks for half the lesson. In order to encourage learners in a monolingual class to participate in pair and group work, it might be worth asking them whether they regard speaking for just three per cent of the lesson to be good value and point out that they can increase that percentage substantially if they try to use English in group activities.

[4] At first, learners may find it strange to use English when communicating with their peers but this is, first and foremost, a question of habit and it is a gradual process. For the teacher to insist that English is used may well be counter-productive and may provoke active resistance. If the task is in English, on the other hand, and learners have to communicate with each other about the task, some English will inevitably be used. It may be very little at first but, as with any habit, it should increase noticeably as time goes by. Indeed, it is not unusual to hear more motivated learners in a monolingual situation communicating with each other in English outside the classroom.

Conclusion

[5] If the benefits of using English to perform purposeful communicative tasks are clearly explained to the class and if the teacher is not excessively authoritarian in insisting that English must be used, a modest and increasing success rate can be achieved. It is far too much to expect that all learners will immediately begin using English to communicate with their peers all the time. But, if at least some of the class use English some of the time, that should be regarded as a significant step on the road to promoting greater use of English in pair and group work in the monolingual classroom.

Available at: https://www.onestopenglish.com/methodologytips-for-teachers/classroom-management-pair-and-group-workin-efl/esol/146454.article. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

Why can group work be a challenge in monolingual classes?

[1] Firstly, and most obviously, the lack of a need to communicate in English means that any communication between learners in that language will seem artificial and arguably even unnecessary. Secondly, the fact that all the learners in the class share a common culture (and are often all from the same age group) will mean that there will often be a lack of curiosity about what other class members do or think, thus making questionnaire-based activities superfluous. Thirdly, there is the paradox that the more interesting and motivating the activity is (and particularly if it involves a competitive element of some sort), the more likely the learners are to use their mother tongue in order to complete the task successfully or to finish first. Finally, the very fact that more effort is involved to communicate in a foreign language when the same task may be performed with much less effort in the mother tongue will also tend to ensure that very little English is used.

Is group work worth the effort?

[2] Taken as a whole, these factors will probably convince many teachers that it is simply not worth bothering with pair and group work in monolingual classes. This, however, would be to exclude from one’s teaching a whole range of potentially motivating and useful activities and to deny learners the opportunity to communicate in English in class time with anyone but the teacher.

[3] Simple mathematics will tell us that in a one-hour lesson with 20 learners, each learner will speak for just 90 seconds if the teacher speaks for half the lesson. In order to encourage learners in a monolingual class to participate in pair and group work, it might be worth asking them whether they regard speaking for just three per cent of the lesson to be good value and point out that they can increase that percentage substantially if they try to use English in group activities.

[4] At first, learners may find it strange to use English when communicating with their peers but this is, first and foremost, a question of habit and it is a gradual process. For the teacher to insist that English is used may well be counter-productive and may provoke active resistance. If the task is in English, on the other hand, and learners have to communicate with each other about the task, some English will inevitably be used. It may be very little at first but, as with any habit, it should increase noticeably as time goes by. Indeed, it is not unusual to hear more motivated learners in a monolingual situation communicating with each other in English outside the classroom.

Conclusion

[5] If the benefits of using English to perform purposeful communicative tasks are clearly explained to the class and if the teacher is not excessively authoritarian in insisting that English must be used, a modest and increasing success rate can be achieved. It is far too much to expect that all learners will immediately begin using English to communicate with their peers all the time. But, if at least some of the class use English some of the time, that should be regarded as a significant step on the road to promoting greater use of English in pair and group work in the monolingual classroom.

Available at: https://www.onestopenglish.com/methodologytips-for-teachers/classroom-management-pair-and-group-workin-efl/esol/146454.article. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

Why can group work be a challenge in monolingual classes?

[1] Firstly, and most obviously, the lack of a need to communicate in English means that any communication between learners in that language will seem artificial and arguably even unnecessary. Secondly, the fact that all the learners in the class share a common culture (and are often all from the same age group) will mean that there will often be a lack of curiosity about what other class members do or think, thus making questionnaire-based activities superfluous. Thirdly, there is the paradox that the more interesting and motivating the activity is (and particularly if it involves a competitive element of some sort), the more likely the learners are to use their mother tongue in order to complete the task successfully or to finish first. Finally, the very fact that more effort is involved to communicate in a foreign language when the same task may be performed with much less effort in the mother tongue will also tend to ensure that very little English is used.

Is group work worth the effort?

[2] Taken as a whole, these factors will probably convince many teachers that it is simply not worth bothering with pair and group work in monolingual classes. This, however, would be to exclude from one’s teaching a whole range of potentially motivating and useful activities and to deny learners the opportunity to communicate in English in class time with anyone but the teacher.

[3] Simple mathematics will tell us that in a one-hour lesson with 20 learners, each learner will speak for just 90 seconds if the teacher speaks for half the lesson. In order to encourage learners in a monolingual class to participate in pair and group work, it might be worth asking them whether they regard speaking for just three per cent of the lesson to be good value and point out that they can increase that percentage substantially if they try to use English in group activities.

[4] At first, learners may find it strange to use English when communicating with their peers but this is, first and foremost, a question of habit and it is a gradual process. For the teacher to insist that English is used may well be counter-productive and may provoke active resistance. If the task is in English, on the other hand, and learners have to communicate with each other about the task, some English will inevitably be used. It may be very little at first but, as with any habit, it should increase noticeably as time goes by. Indeed, it is not unusual to hear more motivated learners in a monolingual situation communicating with each other in English outside the classroom.

Conclusion

[5] If the benefits of using English to perform purposeful communicative tasks are clearly explained to the class and if the teacher is not excessively authoritarian in insisting that English must be used, a modest and increasing success rate can be achieved. It is far too much to expect that all learners will immediately begin using English to communicate with their peers all the time. But, if at least some of the class use English some of the time, that should be regarded as a significant step on the road to promoting greater use of English in pair and group work in the monolingual classroom.

Available at: https://www.onestopenglish.com/methodologytips-for-teachers/classroom-management-pair-and-group-workin-efl/esol/146454.article. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

Why can group work be a challenge in monolingual classes?

[1] Firstly, and most obviously, the lack of a need to communicate in English means that any communication between learners in that language will seem artificial and arguably even unnecessary. Secondly, the fact that all the learners in the class share a common culture (and are often all from the same age group) will mean that there will often be a lack of curiosity about what other class members do or think, thus making questionnaire-based activities superfluous. Thirdly, there is the paradox that the more interesting and motivating the activity is (and particularly if it involves a competitive element of some sort), the more likely the learners are to use their mother tongue in order to complete the task successfully or to finish first. Finally, the very fact that more effort is involved to communicate in a foreign language when the same task may be performed with much less effort in the mother tongue will also tend to ensure that very little English is used.

Is group work worth the effort?

[2] Taken as a whole, these factors will probably convince many teachers that it is simply not worth bothering with pair and group work in monolingual classes. This, however, would be to exclude from one’s teaching a whole range of potentially motivating and useful activities and to deny learners the opportunity to communicate in English in class time with anyone but the teacher.

[3] Simple mathematics will tell us that in a one-hour lesson with 20 learners, each learner will speak for just 90 seconds if the teacher speaks for half the lesson. In order to encourage learners in a monolingual class to participate in pair and group work, it might be worth asking them whether they regard speaking for just three per cent of the lesson to be good value and point out that they can increase that percentage substantially if they try to use English in group activities.

[4] At first, learners may find it strange to use English when communicating with their peers but this is, first and foremost, a question of habit and it is a gradual process. For the teacher to insist that English is used may well be counter-productive and may provoke active resistance. If the task is in English, on the other hand, and learners have to communicate with each other about the task, some English will inevitably be used. It may be very little at first but, as with any habit, it should increase noticeably as time goes by. Indeed, it is not unusual to hear more motivated learners in a monolingual situation communicating with each other in English outside the classroom.

Conclusion

[5] If the benefits of using English to perform purposeful communicative tasks are clearly explained to the class and if the teacher is not excessively authoritarian in insisting that English must be used, a modest and increasing success rate can be achieved. It is far too much to expect that all learners will immediately begin using English to communicate with their peers all the time. But, if at least some of the class use English some of the time, that should be regarded as a significant step on the road to promoting greater use of English in pair and group work in the monolingual classroom.

Available at: https://www.onestopenglish.com/methodologytips-for-teachers/classroom-management-pair-and-group-workin-efl/esol/146454.article. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

By Clare Lavery

Keeping students’ attention and stopping them from getting distracted is a big challenge. Here are some reasons why students’ attention may wander and ways to keep your classes on track.

• Keep in control. Anticipation is the best form of teacher defence so keep scanning the room, making eye contact with all students. You will catch those who are starting to fidget, look out of window or chat to their mates. Then you can react accordingly before the noise level has distracted everyone and created a situation.

• Keep in tune with the class. Don’t just glide along with the best. If one student answers your questions this is not proof that all the others are following what is being discussed. Aim for responses from as wide a sample as possible. Don’t just accept answers from the 3 or 4 class leaders or you will leave the rest behind.

• Keep checking understanding. Try not to use questions like “Do you understand?” or “Has everyone got that?” Students are notoriously wary of admitting they haven’t understood, especially if their peers are feigning comprehension! Use further questions to see if they have understood the concepts.

• Keep demonstrating. Attention wanders when they don’t know what to do and are too afraid to admit it. Keep your instructions to a minimum and demonstrate what to do rather than giving lengthy or detailed explanations. If nearly half of them are clearly unsure and starting to flounder or chat in their mother tongue, take action. Call on the pairs who are doing the task successfully to demonstrate their work as an example for others then try again.

Changing the pace

Here are some tried and tested techniques for changing the pace of the lesson to keep students awake.

• Chant. Select a weekly chant which rouses students. Students stand or sit, clap along or snap their fingers and repeat the rap you have devised. This can be a quotation for higher levels or a sentence construction covered by lower levels. Make it short, snappy and fun.

• Drill. Use some quick-fire questioning around the class and involve as many as possible. Then get the students to do the questions as well as supplying answers. Use visuals as prompts for this questioning.

• Play a game. Do a 10-minute revision game involving everyone pooling ideas, words or questions. Even a spelling game for beginners does the trick. Word association or memory games work well!

• Give a dictation. They do have to concentrate here! It might be just a short piece of text or a list of words. It could be some lines from a song in the charts.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/

strategies-keeping-attention. Accessed on: April 26, 2022

By Clare Lavery

Keeping students’ attention and stopping them from getting distracted is a big challenge. Here are some reasons why students’ attention may wander and ways to keep your classes on track.

• Keep in control. Anticipation is the best form of teacher defence so keep scanning the room, making eye contact with all students. You will catch those who are starting to fidget, look out of window or chat to their mates. Then you can react accordingly before the noise level has distracted everyone and created a situation.

• Keep in tune with the class. Don’t just glide along with the best. If one student answers your questions this is not proof that all the others are following what is being discussed. Aim for responses from as wide a sample as possible. Don’t just accept answers from the 3 or 4 class leaders or you will leave the rest behind.

• Keep checking understanding. Try not to use questions like “Do you understand?” or “Has everyone got that?” Students are notoriously wary of admitting they haven’t understood, especially if their peers are feigning comprehension! Use further questions to see if they have understood the concepts.

• Keep demonstrating. Attention wanders when they don’t know what to do and are too afraid to admit it. Keep your instructions to a minimum and demonstrate what to do rather than giving lengthy or detailed explanations. If nearly half of them are clearly unsure and starting to flounder or chat in their mother tongue, take action. Call on the pairs who are doing the task successfully to demonstrate their work as an example for others then try again.

Changing the pace

Here are some tried and tested techniques for changing the pace of the lesson to keep students awake.

• Chant. Select a weekly chant which rouses students. Students stand or sit, clap along or snap their fingers and repeat the rap you have devised. This can be a quotation for higher levels or a sentence construction covered by lower levels. Make it short, snappy and fun.

• Drill. Use some quick-fire questioning around the class and involve as many as possible. Then get the students to do the questions as well as supplying answers. Use visuals as prompts for this questioning.

• Play a game. Do a 10-minute revision game involving everyone pooling ideas, words or questions. Even a spelling game for beginners does the trick. Word association or memory games work well!

• Give a dictation. They do have to concentrate here! It might be just a short piece of text or a list of words. It could be some lines from a song in the charts.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/

strategies-keeping-attention. Accessed on: April 26, 2022

By Clare Lavery

Keeping students’ attention and stopping them from getting distracted is a big challenge. Here are some reasons why students’ attention may wander and ways to keep your classes on track.

• Keep in control. Anticipation is the best form of teacher defence so keep scanning the room, making eye contact with all students. You will catch those who are starting to fidget, look out of window or chat to their mates. Then you can react accordingly before the noise level has distracted everyone and created a situation.

• Keep in tune with the class. Don’t just glide along with the best. If one student answers your questions this is not proof that all the others are following what is being discussed. Aim for responses from as wide a sample as possible. Don’t just accept answers from the 3 or 4 class leaders or you will leave the rest behind.

• Keep checking understanding. Try not to use questions like “Do you understand?” or “Has everyone got that?” Students are notoriously wary of admitting they haven’t understood, especially if their peers are feigning comprehension! Use further questions to see if they have understood the concepts.

• Keep demonstrating. Attention wanders when they don’t know what to do and are too afraid to admit it. Keep your instructions to a minimum and demonstrate what to do rather than giving lengthy or detailed explanations. If nearly half of them are clearly unsure and starting to flounder or chat in their mother tongue, take action. Call on the pairs who are doing the task successfully to demonstrate their work as an example for others then try again.

Changing the pace

Here are some tried and tested techniques for changing the pace of the lesson to keep students awake.

• Chant. Select a weekly chant which rouses students. Students stand or sit, clap along or snap their fingers and repeat the rap you have devised. This can be a quotation for higher levels or a sentence construction covered by lower levels. Make it short, snappy and fun.

• Drill. Use some quick-fire questioning around the class and involve as many as possible. Then get the students to do the questions as well as supplying answers. Use visuals as prompts for this questioning.

• Play a game. Do a 10-minute revision game involving everyone pooling ideas, words or questions. Even a spelling game for beginners does the trick. Word association or memory games work well!

• Give a dictation. They do have to concentrate here! It might be just a short piece of text or a list of words. It could be some lines from a song in the charts.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/

strategies-keeping-attention. Accessed on: April 26, 2022

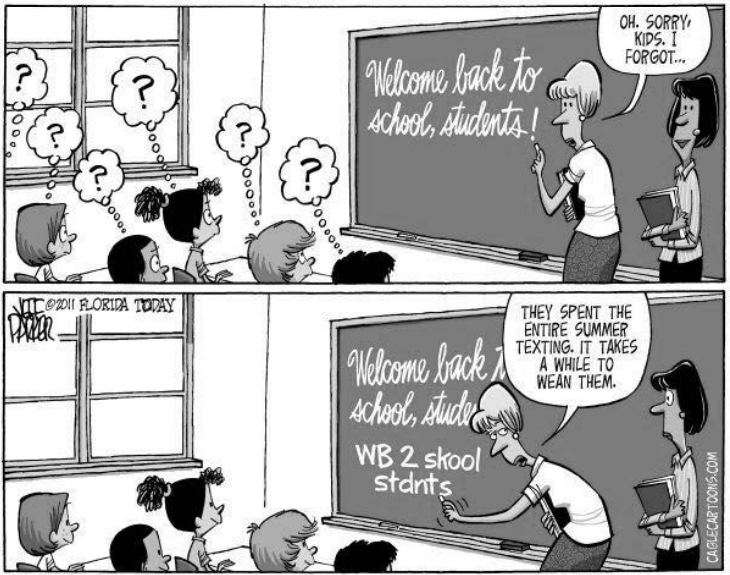

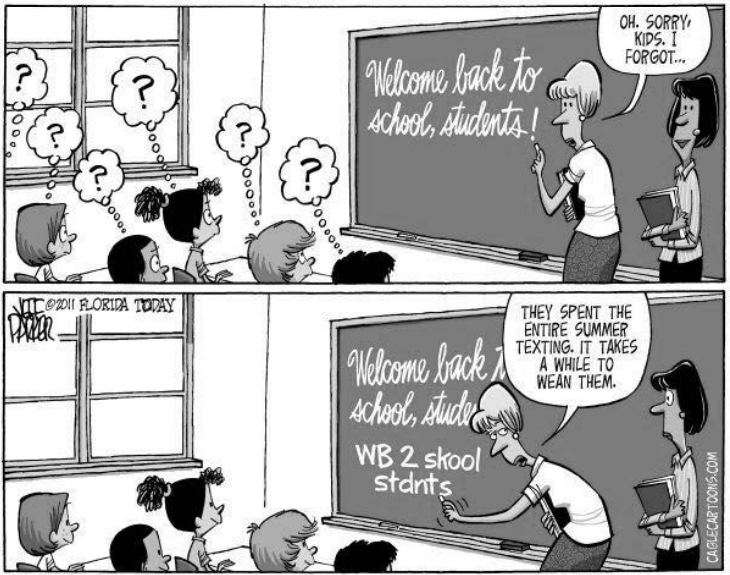

Available at: https://newh.org/news/back-to-school/. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

Available at: https://newh.org/news/back-to-school/. Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

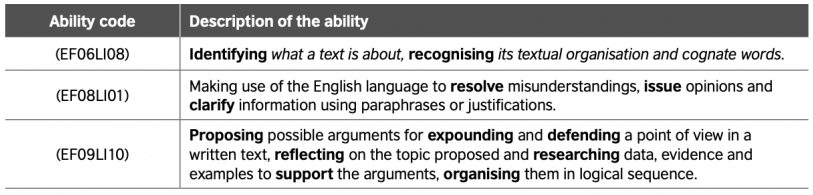

Learning goals, which are referred to in version 3 of the BNCC as abilities, are intended to list the basic knowledge to be acquired by students, and to serve as a reference for drafting and updating the regional, state and municipal curricula. […]

Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org.br/sites/default/files/leitura_critica_bncc_-_en_-_v4_final.pdf. [Fragment] Accessed on: April 26, 2022.

Cognates are words in two languages that share a similar meaning, spelling, and pronunciation. Researchers who study

first and second language acquisition have found that students benefit from cognate awareness. Cognate awareness is the

ability to use cognates in a primary language as a tool for understanding a second language. To develop the BNCC ability

EF06LI08, which includes recognizing cognate words, an English teacher, when working with a group of beginners, may