Questões de Concurso Público COBRA Tecnologia S/A (BB) 2014 para Analista de Operações - Negócios

Foram encontradas 60 questões

do ano na Internet

O artista de rua britânico Banksy foi eleito personalidade do ano na Internet durante os Webby Awards, que premiam todos os anos pioneiros da rede.

O artista, que nunca foi formalmente identificado e vive recluso, foi recompensado por uma exposição organizada em outubro sobre as ruas de Nova York.

Banksy não foi receber o prêmio. A cantora Patti Smith, que entregaria o troféu a ele, ironizou: "Tenho uma confissão a fazer, eu sou Banksy".

A recompensa foi entregue ao apresentador dos Webby Awards, o comediante Patton Oswalt, que leu um discurso do artista, brincando: "Alguém pintou sobre ele".

Com sua exposição "Better Out Than In", Banksy cativou um grande público, a quem oferecia a cada dia uma nova obra de arte nas ruas, que eram fotografadas e divulgadas em seu site www.banksyny.com e em sua conta do Instagram.

Algumas de suas obras foram duramente criticadas pelos proprietários das casas onde foram pintadas, assim como pelo prefeito nova-iorquino da época, Michael Bloomberg.

A cerimônia também comemorou o 25° aniversário da World Wide Web. Seu inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, referiu- se ao debate sobre a neutralidade da Internet. "A Internet deve ser gratuita, aberta e neutra. Depende de nós", declarou sob uma salva de palmas.

Os Webby Awards premiam a excelência na Internet. Criados em 1996, neste ano receberam 12.000 candidaturas provenientes de cerca de 60 países.

(info. abril. com. br/noticias)

do ano na Internet

O artista de rua britânico Banksy foi eleito personalidade do ano na Internet durante os Webby Awards, que premiam todos os anos pioneiros da rede.

O artista, que nunca foi formalmente identificado e vive recluso, foi recompensado por uma exposição organizada em outubro sobre as ruas de Nova York.

Banksy não foi receber o prêmio. A cantora Patti Smith, que entregaria o troféu a ele, ironizou: "Tenho uma confissão a fazer, eu sou Banksy".

A recompensa foi entregue ao apresentador dos Webby Awards, o comediante Patton Oswalt, que leu um discurso do artista, brincando: "Alguém pintou sobre ele".

Com sua exposição "Better Out Than In", Banksy cativou um grande público, a quem oferecia a cada dia uma nova obra de arte nas ruas, que eram fotografadas e divulgadas em seu site www.banksyny.com e em sua conta do Instagram.

Algumas de suas obras foram duramente criticadas pelos proprietários das casas onde foram pintadas, assim como pelo prefeito nova-iorquino da época, Michael Bloomberg.

A cerimônia também comemorou o 25° aniversário da World Wide Web. Seu inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, referiu- se ao debate sobre a neutralidade da Internet. "A Internet deve ser gratuita, aberta e neutra. Depende de nós", declarou sob uma salva de palmas.

Os Webby Awards premiam a excelência na Internet. Criados em 1996, neste ano receberam 12.000 candidaturas provenientes de cerca de 60 países.

(info. abril. com. br/noticias)

I. ...que premiam todos os anos pioneiros da rede. (Oração subordinada adjetiva).

II. O artista foi recompensado por uma exposição organizada em outubro sobre as ruas de Nova York. (Oração subordinada adverbial causai).

III. Banksy não foi receber o prêmio. (Oração absoluta).

IV. Os Webby Awards premiam a excelência na Internet. (Oração coordenada assindética).

Considerando os períodos acima dentro do texto, pode-se afirmar que:

do ano na Internet

O artista de rua britânico Banksy foi eleito personalidade do ano na Internet durante os Webby Awards, que premiam todos os anos pioneiros da rede.

O artista, que nunca foi formalmente identificado e vive recluso, foi recompensado por uma exposição organizada em outubro sobre as ruas de Nova York.

Banksy não foi receber o prêmio. A cantora Patti Smith, que entregaria o troféu a ele, ironizou: "Tenho uma confissão a fazer, eu sou Banksy".

A recompensa foi entregue ao apresentador dos Webby Awards, o comediante Patton Oswalt, que leu um discurso do artista, brincando: "Alguém pintou sobre ele".

Com sua exposição "Better Out Than In", Banksy cativou um grande público, a quem oferecia a cada dia uma nova obra de arte nas ruas, que eram fotografadas e divulgadas em seu site www.banksyny.com e em sua conta do Instagram.

Algumas de suas obras foram duramente criticadas pelos proprietários das casas onde foram pintadas, assim como pelo prefeito nova-iorquino da época, Michael Bloomberg.

A cerimônia também comemorou o 25° aniversário da World Wide Web. Seu inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, referiu- se ao debate sobre a neutralidade da Internet. "A Internet deve ser gratuita, aberta e neutra. Depende de nós", declarou sob uma salva de palmas.

Os Webby Awards premiam a excelência na Internet. Criados em 1996, neste ano receberam 12.000 candidaturas provenientes de cerca de 60 países.

(info. abril. com. br/noticias)

Sobre a palavra "enorme", no texto da tira, pode-se afirmar que:

?

?I. A linguagem é, exclusivamente, verbal.

II. Temos, exclusivamente, a função metalinguística.

III. O humor se constrói apenas na linguagem não verbal.

Pode-se concluir que:

?

? ?

?

Sobre essa função, é possível afirmar que:

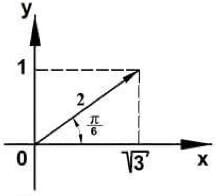

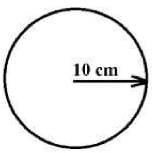

Assinale a alternativa que contém o valor do argumento desse número complexo.

Informatics education:

Europe cannot afford to miss the boat

Principies for an effective informatics curriculum

The committee performed a comprehensive review of the considerabie existing material on building informatics curricula, including among many others the (UK) Royal Society report, the CSPrinciples site, the Computing at Schools Initiative, and the work of the CSTA. Two major conclusions follow from that review.

The first is the sheer number of existing experiences demonstrating that it is indeed possible to teach informatics successfully in primary and secondary education. The second conclusion is in the form of two core principies for such curricula. Existing experiences use a wide variety of approaches; there is no standard curriculum yet, and it was not part of the Committee's mission to define such a standard informatics curriculum for the whole of Europe. The committee has found, however, that while views diverge on the details, a remarkable consensus exists among experts on the basics of what a school informatics curriculum should (and should not) include. On the basis of that existing work, the Committee has identified two principies: leverage students' creativity, emphasize quality.

Leverage student creativity

A powerful aid for informatics teaching is the topic's potential for stimulating students; creativity. The barriers to innovation are often lower than in other disciplines; the technical equipment (computers) is ubiquitous and considerably less expensive. Opportunities exist even for a beginner: with proper guidance, a Creative student can quickly start writing a program or a Web Service, see the results right away, and make them available to numerous other people. Informatics education should draw on this phenomenon and channel the creativity into useful directions, while warning students away from nefarious directions such as destructive "hacking". The example of HFOSS (Humanitarian Free and Open Software Systems)

shows the way towards constructive societal contributions based on informatics.

Informatics education must not just dwell on imparting information to students. It must draw attention to aspects of informatics that immediately appeal to young students, to encourage interaction, to bring abstract concepts to life through visualization and animation; a typical application of this idea is the careful use of (non- violent) games.

Foster quality

Curious students are always going to learn some IT and in particular some programming outside of informatics education through games scripting, Web site development, or adding software components to social networks. Informatics education must emphasize quality, in particular software quality, including the need for correctness (proper functioning of software), for good user interfaces, for taking the needs of users into consideration including psychological and social concerns. The role of informatics education here is:

• To convey the distinction between mere "coding" and software development as a constructive activity based on scientific and engineering principies.

• To dispel the wrong image of programming as an activity for "nerds" and emphasize its human, user-centered aspects, a focus that helps attract students of both genders.

Breaking the teacher availability deadlock

An obstacle to generalizing informatics education is the lack of teachers. It follows from a chicken-and-egg problem: as long as informatics is not in the curriculum, there is Iittle incentive to educate teachers in the subject; as long as there are no teachers, there is Iittle incentive to introduce the subject.

To bring informatics education to the levei that their schools deserve, European countries will have to take both long-term and short-term initiatives:

• Universities, in particular through their informatics departments, must put in place comprehensive programs to train informatics teachers, able to teach digital literacy and informatics under the same intellectual standards as in mathematics, physics and other Sciences.

• The current chicken-and-egg situation is not an excuse for deferring the start of urgently needed efforts. Existing experiences conclusively show that it is possible to break the deadlock. For example, a recent New York Times article explains how IT companies such as Microsoft and Google, conscious of the need to improve the state of education, allow some of their most committed engineers and researchers in the US to pair up with high school teachers to teach computational thinking. In Russia, it is common for academics who graduated from the best high schools to go back to these schools, also on a volunteer basis, and help teachers introduce the concepts of modern informatics. Ali these efforts respect the principie that outsiders must always be paired with current high-school teachers.

(Excerpt of ' Report ofthe joint Informatics Europe & ACM Europe Working Group on Informatics Education April 2013')

Informatics education:

Europe cannot afford to miss the boat

Principies for an effective informatics curriculum

The committee performed a comprehensive review of the considerabie existing material on building informatics curricula, including among many others the (UK) Royal Society report, the CSPrinciples site, the Computing at Schools Initiative, and the work of the CSTA. Two major conclusions follow from that review.

The first is the sheer number of existing experiences demonstrating that it is indeed possible to teach informatics successfully in primary and secondary education. The second conclusion is in the form of two core principies for such curricula. Existing experiences use a wide variety of approaches; there is no standard curriculum yet, and it was not part of the Committee's mission to define such a standard informatics curriculum for the whole of Europe. The committee has found, however, that while views diverge on the details, a remarkable consensus exists among experts on the basics of what a school informatics curriculum should (and should not) include. On the basis of that existing work, the Committee has identified two principies: leverage students' creativity, emphasize quality.

Leverage student creativity

A powerful aid for informatics teaching is the topic's potential for stimulating students; creativity. The barriers to innovation are often lower than in other disciplines; the technical equipment (computers) is ubiquitous and considerably less expensive. Opportunities exist even for a beginner: with proper guidance, a Creative student can quickly start writing a program or a Web Service, see the results right away, and make them available to numerous other people. Informatics education should draw on this phenomenon and channel the creativity into useful directions, while warning students away from nefarious directions such as destructive "hacking". The example of HFOSS (Humanitarian Free and Open Software Systems)

shows the way towards constructive societal contributions based on informatics.

Informatics education must not just dwell on imparting information to students. It must draw attention to aspects of informatics that immediately appeal to young students, to encourage interaction, to bring abstract concepts to life through visualization and animation; a typical application of this idea is the careful use of (non- violent) games.

Foster quality

Curious students are always going to learn some IT and in particular some programming outside of informatics education through games scripting, Web site development, or adding software components to social networks. Informatics education must emphasize quality, in particular software quality, including the need for correctness (proper functioning of software), for good user interfaces, for taking the needs of users into consideration including psychological and social concerns. The role of informatics education here is:

• To convey the distinction between mere "coding" and software development as a constructive activity based on scientific and engineering principies.

• To dispel the wrong image of programming as an activity for "nerds" and emphasize its human, user-centered aspects, a focus that helps attract students of both genders.

Breaking the teacher availability deadlock

An obstacle to generalizing informatics education is the lack of teachers. It follows from a chicken-and-egg problem: as long as informatics is not in the curriculum, there is Iittle incentive to educate teachers in the subject; as long as there are no teachers, there is Iittle incentive to introduce the subject.

To bring informatics education to the levei that their schools deserve, European countries will have to take both long-term and short-term initiatives:

• Universities, in particular through their informatics departments, must put in place comprehensive programs to train informatics teachers, able to teach digital literacy and informatics under the same intellectual standards as in mathematics, physics and other Sciences.

• The current chicken-and-egg situation is not an excuse for deferring the start of urgently needed efforts. Existing experiences conclusively show that it is possible to break the deadlock. For example, a recent New York Times article explains how IT companies such as Microsoft and Google, conscious of the need to improve the state of education, allow some of their most committed engineers and researchers in the US to pair up with high school teachers to teach computational thinking. In Russia, it is common for academics who graduated from the best high schools to go back to these schools, also on a volunteer basis, and help teachers introduce the concepts of modern informatics. Ali these efforts respect the principie that outsiders must always be paired with current high-school teachers.

(Excerpt of ' Report ofthe joint Informatics Europe & ACM Europe Working Group on Informatics Education April 2013')

Informatics education:

Europe cannot afford to miss the boat

Principies for an effective informatics curriculum

The committee performed a comprehensive review of the considerabie existing material on building informatics curricula, including among many others the (UK) Royal Society report, the CSPrinciples site, the Computing at Schools Initiative, and the work of the CSTA. Two major conclusions follow from that review.

The first is the sheer number of existing experiences demonstrating that it is indeed possible to teach informatics successfully in primary and secondary education. The second conclusion is in the form of two core principies for such curricula. Existing experiences use a wide variety of approaches; there is no standard curriculum yet, and it was not part of the Committee's mission to define such a standard informatics curriculum for the whole of Europe. The committee has found, however, that while views diverge on the details, a remarkable consensus exists among experts on the basics of what a school informatics curriculum should (and should not) include. On the basis of that existing work, the Committee has identified two principies: leverage students' creativity, emphasize quality.

Leverage student creativity

A powerful aid for informatics teaching is the topic's potential for stimulating students; creativity. The barriers to innovation are often lower than in other disciplines; the technical equipment (computers) is ubiquitous and considerably less expensive. Opportunities exist even for a beginner: with proper guidance, a Creative student can quickly start writing a program or a Web Service, see the results right away, and make them available to numerous other people. Informatics education should draw on this phenomenon and channel the creativity into useful directions, while warning students away from nefarious directions such as destructive "hacking". The example of HFOSS (Humanitarian Free and Open Software Systems)

shows the way towards constructive societal contributions based on informatics.

Informatics education must not just dwell on imparting information to students. It must draw attention to aspects of informatics that immediately appeal to young students, to encourage interaction, to bring abstract concepts to life through visualization and animation; a typical application of this idea is the careful use of (non- violent) games.

Foster quality

Curious students are always going to learn some IT and in particular some programming outside of informatics education through games scripting, Web site development, or adding software components to social networks. Informatics education must emphasize quality, in particular software quality, including the need for correctness (proper functioning of software), for good user interfaces, for taking the needs of users into consideration including psychological and social concerns. The role of informatics education here is:

• To convey the distinction between mere "coding" and software development as a constructive activity based on scientific and engineering principies.

• To dispel the wrong image of programming as an activity for "nerds" and emphasize its human, user-centered aspects, a focus that helps attract students of both genders.

Breaking the teacher availability deadlock

An obstacle to generalizing informatics education is the lack of teachers. It follows from a chicken-and-egg problem: as long as informatics is not in the curriculum, there is Iittle incentive to educate teachers in the subject; as long as there are no teachers, there is Iittle incentive to introduce the subject.

To bring informatics education to the levei that their schools deserve, European countries will have to take both long-term and short-term initiatives:

• Universities, in particular through their informatics departments, must put in place comprehensive programs to train informatics teachers, able to teach digital literacy and informatics under the same intellectual standards as in mathematics, physics and other Sciences.

• The current chicken-and-egg situation is not an excuse for deferring the start of urgently needed efforts. Existing experiences conclusively show that it is possible to break the deadlock. For example, a recent New York Times article explains how IT companies such as Microsoft and Google, conscious of the need to improve the state of education, allow some of their most committed engineers and researchers in the US to pair up with high school teachers to teach computational thinking. In Russia, it is common for academics who graduated from the best high schools to go back to these schools, also on a volunteer basis, and help teachers introduce the concepts of modern informatics. Ali these efforts respect the principie that outsiders must always be paired with current high-school teachers.

(Excerpt of ' Report ofthe joint Informatics Europe & ACM Europe Working Group on Informatics Education April 2013')

Informatics education:

Europe cannot afford to miss the boat

Principies for an effective informatics curriculum

The committee performed a comprehensive review of the considerabie existing material on building informatics curricula, including among many others the (UK) Royal Society report, the CSPrinciples site, the Computing at Schools Initiative, and the work of the CSTA. Two major conclusions follow from that review.

The first is the sheer number of existing experiences demonstrating that it is indeed possible to teach informatics successfully in primary and secondary education. The second conclusion is in the form of two core principies for such curricula. Existing experiences use a wide variety of approaches; there is no standard curriculum yet, and it was not part of the Committee's mission to define such a standard informatics curriculum for the whole of Europe. The committee has found, however, that while views diverge on the details, a remarkable consensus exists among experts on the basics of what a school informatics curriculum should (and should not) include. On the basis of that existing work, the Committee has identified two principies: leverage students' creativity, emphasize quality.

Leverage student creativity

A powerful aid for informatics teaching is the topic's potential for stimulating students; creativity. The barriers to innovation are often lower than in other disciplines; the technical equipment (computers) is ubiquitous and considerably less expensive. Opportunities exist even for a beginner: with proper guidance, a Creative student can quickly start writing a program or a Web Service, see the results right away, and make them available to numerous other people. Informatics education should draw on this phenomenon and channel the creativity into useful directions, while warning students away from nefarious directions such as destructive "hacking". The example of HFOSS (Humanitarian Free and Open Software Systems)

shows the way towards constructive societal contributions based on informatics.

Informatics education must not just dwell on imparting information to students. It must draw attention to aspects of informatics that immediately appeal to young students, to encourage interaction, to bring abstract concepts to life through visualization and animation; a typical application of this idea is the careful use of (non- violent) games.

Foster quality

Curious students are always going to learn some IT and in particular some programming outside of informatics education through games scripting, Web site development, or adding software components to social networks. Informatics education must emphasize quality, in particular software quality, including the need for correctness (proper functioning of software), for good user interfaces, for taking the needs of users into consideration including psychological and social concerns. The role of informatics education here is:

• To convey the distinction between mere "coding" and software development as a constructive activity based on scientific and engineering principies.

• To dispel the wrong image of programming as an activity for "nerds" and emphasize its human, user-centered aspects, a focus that helps attract students of both genders.

Breaking the teacher availability deadlock

An obstacle to generalizing informatics education is the lack of teachers. It follows from a chicken-and-egg problem: as long as informatics is not in the curriculum, there is Iittle incentive to educate teachers in the subject; as long as there are no teachers, there is Iittle incentive to introduce the subject.

To bring informatics education to the levei that their schools deserve, European countries will have to take both long-term and short-term initiatives:

• Universities, in particular through their informatics departments, must put in place comprehensive programs to train informatics teachers, able to teach digital literacy and informatics under the same intellectual standards as in mathematics, physics and other Sciences.

• The current chicken-and-egg situation is not an excuse for deferring the start of urgently needed efforts. Existing experiences conclusively show that it is possible to break the deadlock. For example, a recent New York Times article explains how IT companies such as Microsoft and Google, conscious of the need to improve the state of education, allow some of their most committed engineers and researchers in the US to pair up with high school teachers to teach computational thinking. In Russia, it is common for academics who graduated from the best high schools to go back to these schools, also on a volunteer basis, and help teachers introduce the concepts of modern informatics. Ali these efforts respect the principie that outsiders must always be paired with current high-school teachers.

(Excerpt of ' Report ofthe joint Informatics Europe & ACM Europe Working Group on Informatics Education April 2013')

Informatics education:

Europe cannot afford to miss the boat

Principies for an effective informatics curriculum

The committee performed a comprehensive review of the considerabie existing material on building informatics curricula, including among many others the (UK) Royal Society report, the CSPrinciples site, the Computing at Schools Initiative, and the work of the CSTA. Two major conclusions follow from that review.

The first is the sheer number of existing experiences demonstrating that it is indeed possible to teach informatics successfully in primary and secondary education. The second conclusion is in the form of two core principies for such curricula. Existing experiences use a wide variety of approaches; there is no standard curriculum yet, and it was not part of the Committee's mission to define such a standard informatics curriculum for the whole of Europe. The committee has found, however, that while views diverge on the details, a remarkable consensus exists among experts on the basics of what a school informatics curriculum should (and should not) include. On the basis of that existing work, the Committee has identified two principies: leverage students' creativity, emphasize quality.

Leverage student creativity

A powerful aid for informatics teaching is the topic's potential for stimulating students; creativity. The barriers to innovation are often lower than in other disciplines; the technical equipment (computers) is ubiquitous and considerably less expensive. Opportunities exist even for a beginner: with proper guidance, a Creative student can quickly start writing a program or a Web Service, see the results right away, and make them available to numerous other people. Informatics education should draw on this phenomenon and channel the creativity into useful directions, while warning students away from nefarious directions such as destructive "hacking". The example of HFOSS (Humanitarian Free and Open Software Systems)

shows the way towards constructive societal contributions based on informatics.

Informatics education must not just dwell on imparting information to students. It must draw attention to aspects of informatics that immediately appeal to young students, to encourage interaction, to bring abstract concepts to life through visualization and animation; a typical application of this idea is the careful use of (non- violent) games.

Foster quality

Curious students are always going to learn some IT and in particular some programming outside of informatics education through games scripting, Web site development, or adding software components to social networks. Informatics education must emphasize quality, in particular software quality, including the need for correctness (proper functioning of software), for good user interfaces, for taking the needs of users into consideration including psychological and social concerns. The role of informatics education here is:

• To convey the distinction between mere "coding" and software development as a constructive activity based on scientific and engineering principies.

• To dispel the wrong image of programming as an activity for "nerds" and emphasize its human, user-centered aspects, a focus that helps attract students of both genders.

Breaking the teacher availability deadlock

An obstacle to generalizing informatics education is the lack of teachers. It follows from a chicken-and-egg problem: as long as informatics is not in the curriculum, there is Iittle incentive to educate teachers in the subject; as long as there are no teachers, there is Iittle incentive to introduce the subject.

To bring informatics education to the levei that their schools deserve, European countries will have to take both long-term and short-term initiatives:

• Universities, in particular through their informatics departments, must put in place comprehensive programs to train informatics teachers, able to teach digital literacy and informatics under the same intellectual standards as in mathematics, physics and other Sciences.

• The current chicken-and-egg situation is not an excuse for deferring the start of urgently needed efforts. Existing experiences conclusively show that it is possible to break the deadlock. For example, a recent New York Times article explains how IT companies such as Microsoft and Google, conscious of the need to improve the state of education, allow some of their most committed engineers and researchers in the US to pair up with high school teachers to teach computational thinking. In Russia, it is common for academics who graduated from the best high schools to go back to these schools, also on a volunteer basis, and help teachers introduce the concepts of modern informatics. Ali these efforts respect the principie that outsiders must always be paired with current high-school teachers.

(Excerpt of ' Report ofthe joint Informatics Europe & ACM Europe Working Group on Informatics Education April 2013')