Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para cesgranrio

Foram encontradas 27.571 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

FIGUEIREDO, Vânia Santos. Perspectivas de recuperação para áreas em processo de desertificação no semiárido da Paraíba – Brasil. In: Revista Electrónica de Geografia y Ciencias Sociales da Universitat de Barcelona. Disponível em: https:// revistes.ub.edu. Acesso em: 21 jan. 2021. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] Com base no texto, para além dos fatores antrópicos, o aspecto geográfico que intensifica o processo de desertificação no município da região indicada é a

Disponível em: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br. Acesso em: 29 dez. 2019. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] O texto indica que a situação de esgotamento mencionada é consequência do processo de

FREYRE, Gilberto. Casa-grande & senzala. São Paulo: Global, 2006. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] Sobre os indígenas, o texto apresentado expõe uma visão que consiste em indicar que esses nativos foram seres

Disponível em: https://acervo.oglobo.globo.com. Acesso em: 21 out. 2019.

[Questão Inédita] As medidas econômicas citadas foram implementadas com o objetivo de

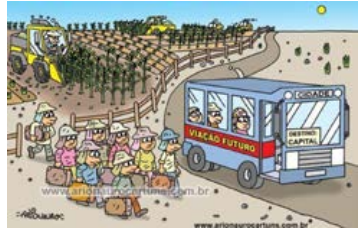

[Questão Inédita] A charge expressa um tipo de migração conhecido como

Disponível em: https://exame.abril.com.br. Acesso em: 13 set. 2019. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] De acordo com o texto, é possível perceber que a política econômica desse governo buscava

SILVA, Suely Braga da. 50 anos em 5: O Plano de Metas. FGV. Disponível em: https://cpdoc.fgv.br. Acesso em: 20 set. 2019.

[Questão Inédita] O texto indica que o programa político desenvolvimentista mencionado promoveu o(a)

GOMES, Angela Maria de Castro. A invenção do trabalhismo. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2005. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] As ações do governo brasileiro na Segunda Guerra Mundial descritas no texto colocaram o país em uma posição de

LEAL, Victor Nunes. Coronelismo, enxada e voto: o município e o regime representativo no Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia da Letras, 2012.

[Questão Inédita] O texto indica que o fenômeno social mencionado

ALMEIDA, Leones A. de et al. Melhoramento da soja para regiões de baixa latitude. In: QUEIROZ, M. A. de et al. (ed.) Recursos Genéticos e Melhoramento de Plantas para o Nordeste Brasileiro. Petrolina, PE: Embrapa Semiárido, 1999. Disponível em: http://www.cpatsa.embrapa.br. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2022. (adaptado)

[Questão Inédita] O texto indica que a aplicação de técnicas no cultivo de soja no Brasil foi necessária para

[…]

A vontade do rio de voltar Às vezes sacode de algum lugar Ele dorme até a chuva chegar Mas a tempestade vem anunciar E uma enchente lembra a população Que o que é rua antes era vazão E uma enchente lembra a população Que o que é rua antes era vazão Alô, Tietê, Água Preta, Iquiririm Minhas Iarinhas andam cantando Suas ladainhas para mim “Iarinhas”, de Luiza Lian.

Disponível em: https://www. letras.mus.br. Acesso em: 16 maio 2021.

A canção expõe a denúncia de um problema social urbano que é potencializado pela