Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para professor - inglês

Foram encontradas 12.753 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Faz alguns anos que um grupo de amigos se reúne comigo para ler poesia. Numa dessas reuniões nos deparamos com esta afirmação de Gandhi: “Eu nunca acreditei que a sobrevivência fosse um valor último. A vida, para ser bela, deve estar cercada de vontade, de bondade e de liberdade. Essas são coisas pelas quais vale a pena morrer”. Essas palavras provocaram um silêncio meditativo, até que um dos membros do grupo, que se chama Canoeiros, sugeriu que fizéssemos um exercício espiritual. Um joguinho de “faz de conta”. “Vamos fazer de conta que sabemos que temos apenas um ano a mais de vida. Como é que viveremos sabendo que o tempo é curto?”

A consciência da morte nos dá uma maravilhosa lucidez. D. Juan, o bruxo do livro de Carlos Castañeda, Viagem a Ixtlan, advertia seu discípulo: “Essa bem pode ser a sua última batalha sobre a terra”. Sim, bem pode ser. Somente os tolos pensam de outra forma. E se ela pode ser a última batalha, que seja uma batalha que valha a pena. E, com isso, nos libertamos de uma infinidade de coisas ptolas e mesquinhas que permitimos se aninhem em nossos pensamentos e coração. Resta então a pergunta: “O que é o essencial?”. Um conhecido meu, ao saber que tinha um câncer no cérebro e que lhe restavam não mais que seis meses de vida, começou uma vida nova. As etiquetas sociais não mais faziam sentido. Passou a receber somente as pessoas que desejava receber, os amigos, com quem podia compartilhar seus sentimentos. Eliot se refere a um tempo em que ficamos livres da compulsão prática – fazer, fazer, fazer. Não havia mais nada a fazer. Era hora de se entregar inteiramente ao deleite da vida: ver os cenários que ele amava, ouvir as músicas que lhe davam prazer, ler os textos antigos que o haviam alimentado.

O fato é que, sem que o saibamos, todos nós estamos enfermos de morte e é preciso viver a vida com sabedoria para que ela, a vida, não seja estragada pela loucura que nos cerca.

(Rubem Alves. Variações sobre o prazer: Santo Agostinho, Nietzsche, Marx e Babette. São Paulo, Editora Planeta do Brasil, 2011. Adaptado)

Faz alguns anos que um grupo de amigos se reúne comigo para ler poesia. Numa dessas reuniões nos deparamos com esta afirmação de Gandhi: “Eu nunca acreditei que a sobrevivência fosse um valor último. A vida, para ser bela, deve estar cercada de vontade, de bondade e de liberdade. Essas são coisas pelas quais vale a pena morrer”. Essas palavras provocaram um silêncio meditativo, até que um dos membros do grupo, que se chama Canoeiros, sugeriu que fizéssemos um exercício espiritual. Um joguinho de “faz de conta”. “Vamos fazer de conta que sabemos que temos apenas um ano a mais de vida. Como é que viveremos sabendo que o tempo é curto?”

A consciência da morte nos dá uma maravilhosa lucidez. D. Juan, o bruxo do livro de Carlos Castañeda, Viagem a Ixtlan, advertia seu discípulo: “Essa bem pode ser a sua última batalha sobre a terra”. Sim, bem pode ser. Somente os tolos pensam de outra forma. E se ela pode ser a última batalha, que seja uma batalha que valha a pena. E, com isso, nos libertamos de uma infinidade de coisas ptolas e mesquinhas que permitimos se aninhem em nossos pensamentos e coração. Resta então a pergunta: “O que é o essencial?”. Um conhecido meu, ao saber que tinha um câncer no cérebro e que lhe restavam não mais que seis meses de vida, começou uma vida nova. As etiquetas sociais não mais faziam sentido. Passou a receber somente as pessoas que desejava receber, os amigos, com quem podia compartilhar seus sentimentos. Eliot se refere a um tempo em que ficamos livres da compulsão prática – fazer, fazer, fazer. Não havia mais nada a fazer. Era hora de se entregar inteiramente ao deleite da vida: ver os cenários que ele amava, ouvir as músicas que lhe davam prazer, ler os textos antigos que o haviam alimentado.

O fato é que, sem que o saibamos, todos nós estamos enfermos de morte e é preciso viver a vida com sabedoria para que ela, a vida, não seja estragada pela loucura que nos cerca.

(Rubem Alves. Variações sobre o prazer: Santo Agostinho, Nietzsche, Marx e Babette. São Paulo, Editora Planeta do Brasil, 2011. Adaptado)

Faz alguns anos que um grupo de amigos se reúne comigo para ler poesia. Numa dessas reuniões nos deparamos com esta afirmação de Gandhi: “Eu nunca acreditei que a sobrevivência fosse um valor último. A vida, para ser bela, deve estar cercada de vontade, de bondade e de liberdade. Essas são coisas pelas quais vale a pena morrer”. Essas palavras provocaram um silêncio meditativo, até que um dos membros do grupo, que se chama Canoeiros, sugeriu que fizéssemos um exercício espiritual. Um joguinho de “faz de conta”. “Vamos fazer de conta que sabemos que temos apenas um ano a mais de vida. Como é que viveremos sabendo que o tempo é curto?”

A consciência da morte nos dá uma maravilhosa lucidez. D. Juan, o bruxo do livro de Carlos Castañeda, Viagem a Ixtlan, advertia seu discípulo: “Essa bem pode ser a sua última batalha sobre a terra”. Sim, bem pode ser. Somente os tolos pensam de outra forma. E se ela pode ser a última batalha, que seja uma batalha que valha a pena. E, com isso, nos libertamos de uma infinidade de coisas ptolas e mesquinhas que permitimos se aninhem em nossos pensamentos e coração. Resta então a pergunta: “O que é o essencial?”. Um conhecido meu, ao saber que tinha um câncer no cérebro e que lhe restavam não mais que seis meses de vida, começou uma vida nova. As etiquetas sociais não mais faziam sentido. Passou a receber somente as pessoas que desejava receber, os amigos, com quem podia compartilhar seus sentimentos. Eliot se refere a um tempo em que ficamos livres da compulsão prática – fazer, fazer, fazer. Não havia mais nada a fazer. Era hora de se entregar inteiramente ao deleite da vida: ver os cenários que ele amava, ouvir as músicas que lhe davam prazer, ler os textos antigos que o haviam alimentado.

O fato é que, sem que o saibamos, todos nós estamos enfermos de morte e é preciso viver a vida com sabedoria para que ela, a vida, não seja estragada pela loucura que nos cerca.

(Rubem Alves. Variações sobre o prazer: Santo Agostinho, Nietzsche, Marx e Babette. São Paulo, Editora Planeta do Brasil, 2011. Adaptado)

Faz alguns anos que um grupo de amigos se reúne comigo para ler poesia. Numa dessas reuniões nos deparamos com esta afirmação de Gandhi: “Eu nunca acreditei que a sobrevivência fosse um valor último. A vida, para ser bela, deve estar cercada de vontade, de bondade e de liberdade. Essas são coisas pelas quais vale a pena morrer”. Essas palavras provocaram um silêncio meditativo, até que um dos membros do grupo, que se chama Canoeiros, sugeriu que fizéssemos um exercício espiritual. Um joguinho de “faz de conta”. “Vamos fazer de conta que sabemos que temos apenas um ano a mais de vida. Como é que viveremos sabendo que o tempo é curto?”

A consciência da morte nos dá uma maravilhosa lucidez. D. Juan, o bruxo do livro de Carlos Castañeda, Viagem a Ixtlan, advertia seu discípulo: “Essa bem pode ser a sua última batalha sobre a terra”. Sim, bem pode ser. Somente os tolos pensam de outra forma. E se ela pode ser a última batalha, que seja uma batalha que valha a pena. E, com isso, nos libertamos de uma infinidade de coisas ptolas e mesquinhas que permitimos se aninhem em nossos pensamentos e coração. Resta então a pergunta: “O que é o essencial?”. Um conhecido meu, ao saber que tinha um câncer no cérebro e que lhe restavam não mais que seis meses de vida, começou uma vida nova. As etiquetas sociais não mais faziam sentido. Passou a receber somente as pessoas que desejava receber, os amigos, com quem podia compartilhar seus sentimentos. Eliot se refere a um tempo em que ficamos livres da compulsão prática – fazer, fazer, fazer. Não havia mais nada a fazer. Era hora de se entregar inteiramente ao deleite da vida: ver os cenários que ele amava, ouvir as músicas que lhe davam prazer, ler os textos antigos que o haviam alimentado.

O fato é que, sem que o saibamos, todos nós estamos enfermos de morte e é preciso viver a vida com sabedoria para que ela, a vida, não seja estragada pela loucura que nos cerca.

(Rubem Alves. Variações sobre o prazer: Santo Agostinho, Nietzsche, Marx e Babette. São Paulo, Editora Planeta do Brasil, 2011. Adaptado)

Faz alguns anos que um grupo de amigos se reúne comigo para ler poesia. Numa dessas reuniões nos deparamos com esta afirmação de Gandhi: “Eu nunca acreditei que a sobrevivência fosse um valor último. A vida, para ser bela, deve estar cercada de vontade, de bondade e de liberdade. Essas são coisas pelas quais vale a pena morrer”. Essas palavras provocaram um silêncio meditativo, até que um dos membros do grupo, que se chama Canoeiros, sugeriu que fizéssemos um exercício espiritual. Um joguinho de “faz de conta”. “Vamos fazer de conta que sabemos que temos apenas um ano a mais de vida. Como é que viveremos sabendo que o tempo é curto?”

A consciência da morte nos dá uma maravilhosa lucidez. D. Juan, o bruxo do livro de Carlos Castañeda, Viagem a Ixtlan, advertia seu discípulo: “Essa bem pode ser a sua última batalha sobre a terra”. Sim, bem pode ser. Somente os tolos pensam de outra forma. E se ela pode ser a última batalha, que seja uma batalha que valha a pena. E, com isso, nos libertamos de uma infinidade de coisas ptolas e mesquinhas que permitimos se aninhem em nossos pensamentos e coração. Resta então a pergunta: “O que é o essencial?”. Um conhecido meu, ao saber que tinha um câncer no cérebro e que lhe restavam não mais que seis meses de vida, começou uma vida nova. As etiquetas sociais não mais faziam sentido. Passou a receber somente as pessoas que desejava receber, os amigos, com quem podia compartilhar seus sentimentos. Eliot se refere a um tempo em que ficamos livres da compulsão prática – fazer, fazer, fazer. Não havia mais nada a fazer. Era hora de se entregar inteiramente ao deleite da vida: ver os cenários que ele amava, ouvir as músicas que lhe davam prazer, ler os textos antigos que o haviam alimentado.

O fato é que, sem que o saibamos, todos nós estamos enfermos de morte e é preciso viver a vida com sabedoria para que ela, a vida, não seja estragada pela loucura que nos cerca.

(Rubem Alves. Variações sobre o prazer: Santo Agostinho, Nietzsche, Marx e Babette. São Paulo, Editora Planeta do Brasil, 2011. Adaptado)

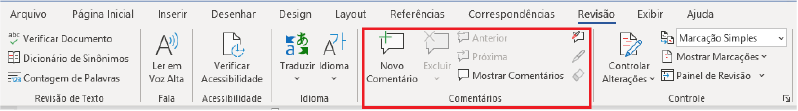

( ) - Não é possível inserir um comentário na área de cabeçalho ou de rodapé de um documento. ( ) - Para imprimir documento sem imprimir os comentários no Microsoft Word 2010, basta clicar em Mostrar Marcações no grupo Controle e desmarcar a caixa de seleção comentários. ( ) - Para responder a um comentário no Microsoft Word 2010 ou 2007, basta clicar em Controlar Alterações no grupo Controle. ( ) - Para ver o nome do autor, a data e a hora em que o comentário foi feito, é só acionar Verificar Acessibilidade no grupo Acessibilidade. ( ) - Um comentário é uma anotação ou anotação que um autor ou revisor pode adicionar a um documento, exibido no painel de revisão ou em um balão na margem do documento.

A sequência CORRETA das afirmações é:

TEXT TWO:

After so long a pause that Marcia felt sure whoever it was must have gone away, the front doorbell rang again, a courteously brief ‘still waiting.’

It would be a neighbor child on the way home from school with a handful of basketball tickets. Or an agent tardily taking orders for cheap and gaudy Christmas cards.

The trip down to the door would be laborious. Doctor Bowen had wanted her to avoid the stairs as much as possible from now on. But the diffident summons sounded very plaintive in its competition with the savage swish of sleet against the windows.

Raising herself heavily on her elbows, Marcia tried to squeeze a prompt decision out of her tousled blonde head with the tips of slim fingers. The mirror of the vanity table ventured a comforting comment on the girlish cornflower fringe that Paul always said brought out the blue in her eyes. She pressed her palms hard on the yellow curls, debating whether to make the effort. In any event she would have to go down soon, for the luncheon table was standing exactly as they had left it, and Paul would be returning in half an hour.

Edging clumsily to the side of the bed, she sat up, momentarily swept with vertigo, and fumbled with her stockinged toes for the shapeless slippers in which she had awkwardly paddled about through two previous campaigns in behalf of humanity’s perpetuity. When done with them, this time, Marcia expected to throw the slippers away.

Roberta eagerly reached up both chubby arms and bounced ecstatically at the approach of the outstretched hands. Wellie scrambled up out of his blocks and detonated an ominously sloppy sneeze.

Marcia said “Please don’t tell me you’ve been taking cold again.”

Wellie denied the accusation with a vigorous shake of his head, whooped hoarsely, and began slowly pacing the intermittent clatter of their procession down he dingy stairway, the flat of his small hand squeaking on the cold rail of the ugly yellow banister.

The bulky figure of a woman was silhouetted on the frosted glass panels of the street door. Wellie, with a wobbly index finger in his nose, halted to reconnoiter as they neared the bottom of the stairs, and his mother gave him a gentle push forward. They were in the front hall now, Marcia irresolutely considering whether to brave the blizzard. Wallie decided this matter by inquiring who it was in a penetrating treble, reinforcing his desire to know by twisting the knob with ineffective hands. Marcia shifted Roberta into the crook of her other arm and opened the door to a breath-taking swirl of stinging snow, the first real storm of the season.

DOUGLAS, Lloyd C. White Banners. New York: P. F. Collier &

Son Corporation, 1936.

TEXT TWO:

After so long a pause that Marcia felt sure whoever it was must have gone away, the front doorbell rang again, a courteously brief ‘still waiting.’

It would be a neighbor child on the way home from school with a handful of basketball tickets. Or an agent tardily taking orders for cheap and gaudy Christmas cards.

The trip down to the door would be laborious. Doctor Bowen had wanted her to avoid the stairs as much as possible from now on. But the diffident summons sounded very plaintive in its competition with the savage swish of sleet against the windows.

Raising herself heavily on her elbows, Marcia tried to squeeze a prompt decision out of her tousled blonde head with the tips of slim fingers. The mirror of the vanity table ventured a comforting comment on the girlish cornflower fringe that Paul always said brought out the blue in her eyes. She pressed her palms hard on the yellow curls, debating whether to make the effort. In any event she would have to go down soon, for the luncheon table was standing exactly as they had left it, and Paul would be returning in half an hour.

Edging clumsily to the side of the bed, she sat up, momentarily swept with vertigo, and fumbled with her stockinged toes for the shapeless slippers in which she had awkwardly paddled about through two previous campaigns in behalf of humanity’s perpetuity. When done with them, this time, Marcia expected to throw the slippers away.

Roberta eagerly reached up both chubby arms and bounced ecstatically at the approach of the outstretched hands. Wellie scrambled up out of his blocks and detonated an ominously sloppy sneeze.

Marcia said “Please don’t tell me you’ve been taking cold again.”

Wellie denied the accusation with a vigorous shake of his head, whooped hoarsely, and began slowly pacing the intermittent clatter of their procession down he dingy stairway, the flat of his small hand squeaking on the cold rail of the ugly yellow banister.

The bulky figure of a woman was silhouetted on the frosted glass panels of the street door. Wellie, with a wobbly index finger in his nose, halted to reconnoiter as they neared the bottom of the stairs, and his mother gave him a gentle push forward. They were in the front hall now, Marcia irresolutely considering whether to brave the blizzard. Wallie decided this matter by inquiring who it was in a penetrating treble, reinforcing his desire to know by twisting the knob with ineffective hands. Marcia shifted Roberta into the crook of her other arm and opened the door to a breath-taking swirl of stinging snow, the first real storm of the season.

DOUGLAS, Lloyd C. White Banners. New York: P. F. Collier &

Son Corporation, 1936.

TEXT TWO:

After so long a pause that Marcia felt sure whoever it was must have gone away, the front doorbell rang again, a courteously brief ‘still waiting.’

It would be a neighbor child on the way home from school with a handful of basketball tickets. Or an agent tardily taking orders for cheap and gaudy Christmas cards.

The trip down to the door would be laborious. Doctor Bowen had wanted her to avoid the stairs as much as possible from now on. But the diffident summons sounded very plaintive in its competition with the savage swish of sleet against the windows.

Raising herself heavily on her elbows, Marcia tried to squeeze a prompt decision out of her tousled blonde head with the tips of slim fingers. The mirror of the vanity table ventured a comforting comment on the girlish cornflower fringe that Paul always said brought out the blue in her eyes. She pressed her palms hard on the yellow curls, debating whether to make the effort. In any event she would have to go down soon, for the luncheon table was standing exactly as they had left it, and Paul would be returning in half an hour.

Edging clumsily to the side of the bed, she sat up, momentarily swept with vertigo, and fumbled with her stockinged toes for the shapeless slippers in which she had awkwardly paddled about through two previous campaigns in behalf of humanity’s perpetuity. When done with them, this time, Marcia expected to throw the slippers away.

Roberta eagerly reached up both chubby arms and bounced ecstatically at the approach of the outstretched hands. Wellie scrambled up out of his blocks and detonated an ominously sloppy sneeze.

Marcia said “Please don’t tell me you’ve been taking cold again.”

Wellie denied the accusation with a vigorous shake of his head, whooped hoarsely, and began slowly pacing the intermittent clatter of their procession down he dingy stairway, the flat of his small hand squeaking on the cold rail of the ugly yellow banister.

The bulky figure of a woman was silhouetted on the frosted glass panels of the street door. Wellie, with a wobbly index finger in his nose, halted to reconnoiter as they neared the bottom of the stairs, and his mother gave him a gentle push forward. They were in the front hall now, Marcia irresolutely considering whether to brave the blizzard. Wallie decided this matter by inquiring who it was in a penetrating treble, reinforcing his desire to know by twisting the knob with ineffective hands. Marcia shifted Roberta into the crook of her other arm and opened the door to a breath-taking swirl of stinging snow, the first real storm of the season.

DOUGLAS, Lloyd C. White Banners. New York: P. F. Collier &

Son Corporation, 1936.

TEXT TWO:

After so long a pause that Marcia felt sure whoever it was must have gone away, the front doorbell rang again, a courteously brief ‘still waiting.’

It would be a neighbor child on the way home from school with a handful of basketball tickets. Or an agent tardily taking orders for cheap and gaudy Christmas cards.

The trip down to the door would be laborious. Doctor Bowen had wanted her to avoid the stairs as much as possible from now on. But the diffident summons sounded very plaintive in its competition with the savage swish of sleet against the windows.

Raising herself heavily on her elbows, Marcia tried to squeeze a prompt decision out of her tousled blonde head with the tips of slim fingers. The mirror of the vanity table ventured a comforting comment on the girlish cornflower fringe that Paul always said brought out the blue in her eyes. She pressed her palms hard on the yellow curls, debating whether to make the effort. In any event she would have to go down soon, for the luncheon table was standing exactly as they had left it, and Paul would be returning in half an hour.

Edging clumsily to the side of the bed, she sat up, momentarily swept with vertigo, and fumbled with her stockinged toes for the shapeless slippers in which she had awkwardly paddled about through two previous campaigns in behalf of humanity’s perpetuity. When done with them, this time, Marcia expected to throw the slippers away.

Roberta eagerly reached up both chubby arms and bounced ecstatically at the approach of the outstretched hands. Wellie scrambled up out of his blocks and detonated an ominously sloppy sneeze.

Marcia said “Please don’t tell me you’ve been taking cold again.”

Wellie denied the accusation with a vigorous shake of his head, whooped hoarsely, and began slowly pacing the intermittent clatter of their procession down he dingy stairway, the flat of his small hand squeaking on the cold rail of the ugly yellow banister.

The bulky figure of a woman was silhouetted on the frosted glass panels of the street door. Wellie, with a wobbly index finger in his nose, halted to reconnoiter as they neared the bottom of the stairs, and his mother gave him a gentle push forward. They were in the front hall now, Marcia irresolutely considering whether to brave the blizzard. Wallie decided this matter by inquiring who it was in a penetrating treble, reinforcing his desire to know by twisting the knob with ineffective hands. Marcia shifted Roberta into the crook of her other arm and opened the door to a breath-taking swirl of stinging snow, the first real storm of the season.

DOUGLAS, Lloyd C. White Banners. New York: P. F. Collier &

Son Corporation, 1936.

TEXT TWO:

After so long a pause that Marcia felt sure whoever it was must have gone away, the front doorbell rang again, a courteously brief ‘still waiting.’

It would be a neighbor child on the way home from school with a handful of basketball tickets. Or an agent tardily taking orders for cheap and gaudy Christmas cards.

The trip down to the door would be laborious. Doctor Bowen had wanted her to avoid the stairs as much as possible from now on. But the diffident summons sounded very plaintive in its competition with the savage swish of sleet against the windows.

Raising herself heavily on her elbows, Marcia tried to squeeze a prompt decision out of her tousled blonde head with the tips of slim fingers. The mirror of the vanity table ventured a comforting comment on the girlish cornflower fringe that Paul always said brought out the blue in her eyes. She pressed her palms hard on the yellow curls, debating whether to make the effort. In any event she would have to go down soon, for the luncheon table was standing exactly as they had left it, and Paul would be returning in half an hour.

Edging clumsily to the side of the bed, she sat up, momentarily swept with vertigo, and fumbled with her stockinged toes for the shapeless slippers in which she had awkwardly paddled about through two previous campaigns in behalf of humanity’s perpetuity. When done with them, this time, Marcia expected to throw the slippers away.

Roberta eagerly reached up both chubby arms and bounced ecstatically at the approach of the outstretched hands. Wellie scrambled up out of his blocks and detonated an ominously sloppy sneeze.

Marcia said “Please don’t tell me you’ve been taking cold again.”

Wellie denied the accusation with a vigorous shake of his head, whooped hoarsely, and began slowly pacing the intermittent clatter of their procession down he dingy stairway, the flat of his small hand squeaking on the cold rail of the ugly yellow banister.

The bulky figure of a woman was silhouetted on the frosted glass panels of the street door. Wellie, with a wobbly index finger in his nose, halted to reconnoiter as they neared the bottom of the stairs, and his mother gave him a gentle push forward. They were in the front hall now, Marcia irresolutely considering whether to brave the blizzard. Wallie decided this matter by inquiring who it was in a penetrating treble, reinforcing his desire to know by twisting the knob with ineffective hands. Marcia shifted Roberta into the crook of her other arm and opened the door to a breath-taking swirl of stinging snow, the first real storm of the season.

DOUGLAS, Lloyd C. White Banners. New York: P. F. Collier &

Son Corporation, 1936.

Which sentences are grammatically CORRECT?

Choose the CORRECT answer.

I. Paula has got short black hairs.

II. We´re going to buy some new furnitures.

III. The tour guide gave us some information about the city.

IV. I read a book and listened to some music.

V. I´m going to open a window to get some fresh air.

Complete the sentence with the CORRECT answer.

Someone _________ my phone!

Complete the sentence with the CORRECT answer.

He _________ home as soon as he_________ his work.