Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para oficial de chancelaria

Foram encontradas 161 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Texto 2 – No começo era o pé

Sim, no começo era o pé. Se está provado, por descobertas arqueológicas, que há sete mil anos estes brasis já eram habitados, pensai nestas legiões e legiões de pés que palmilharam nosso território. E pensai nestes passos, primeiro sem destinos, machados de pedra abrindo as iniciais picadas na floresta. E nos pés dos que subiam às rochas distantes, já feitos pedra também, e nos que se enfeitaram de penas e receberam as primeiras botas dos conquistadores e as primeiras sandálias dos pregadores; pés barrentos, nus, ou enrolados de panos dos caminheiros, pés sobre-humanos dos bandeirantes que alargaram um império, quase sempre arrastando passos e mais passos em chãos desconhecidos, dos marinheiros dos barcos primitivos e dos que subiram aos mastros das grandes naus. Depois o Brasil se fez sedentário numa parte de seu povo. Houve os pés descalços que carregaram os pés calçados, pelas estradas. A moleza das sinhazinhas de pequeninos pés redondos, quase dispensáveis pela falta de exercício. E depois das cadeirinhas, das carruagens, das redes carregadas por escravos, as primeiras grandes estradas já com postos de montaria organizados, o pedágio de vinténs estabelecido já no século XVIII. Mas além da abertura dos portos, depois da primeira etapa da industrialização, com os navios a vapor, as estradas de ferro, o pé de sete milênios da terra do Brasil ainda faz seu caminho.

(Dinah Silveira de Queiroz)

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

A estruturação desse primeiro período do texto 1 mostra:

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

Texto 1 – Um país em berço de sangue

O maior país da América Latina, com a maior população católica do mundo, não nasceu de forma tranquila. Neste livro, com o realismo dos documentos originais, vemos claramente a brutalidade do extermínio dos índios na costa brasileira, berço de sangue cujo marco determinante é a fundação da cidade do Rio de Janeiro.

O Brasil real começou a ser construído por homens como o degredado João Ramalho, que raspava os pelos do corpo para se mesclar aos índios e construiu um exército de mestiços caçadores de escravos mais poderoso que o da própria Coroa; personagens improváveis como o jesuíta Manoel da Nóbrega, padre gago incumbido de catequizar um povo de língua indecifrável, esteio da erradicação dos “hereges” antropófagos; líderes implacáveis como Aimberê, ex-escravo que tomou a frente da resistência e Cunhambebe, cacique “imortal”, que dizia poder devorar carne humana porque era “um jaguar”.

Incluindo protestantes franceses, que se aliaram aos índios para escapar dos portugueses e da Inquisição, além de mamelucos, os primeiros brasileiros verdadeiramente ligados à terra, que falavam tupi tanto quanto o português e partiram do planalto de Piratininga para caçar índios e estenderam a colônia sertão adentro, surge um povo que desde a origem nada tem da autoimagem do “brasileiro cordial”.

(Texto da orelha do livro A conquista do Brasil, de Thales Guaracy, Planeta, Rio de Janeiro, 2015)

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

O Diretor de um certo órgão público incumbiu alguns funcionários das seguintes tarefas:

0 3 6 9 1 2 1 5 1 8 2 1 2 4 2 7 3 0 3 3 3 6 3 9 . . .

Nessa sucessão, o algarismo que deve ocupar a 126ª posição é

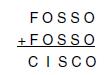

Considerando que letras distintas correspondem a algarismos distintos, quantos anos tem Zeus?