Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para analista - análise e desenvolvimento de sistemas

Foram encontradas 165 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Com relação ao estabelecimento de conexões do protocolo TCP, analise as afirmativas a seguir:

I. Na solicitação de conexão do tipo abertura ativa, um segmento SYN não transporta dados e consome um número de sequência.

II. O procedimento de estabelecimento de conexão é suscetível a problemas de segurança e os ataques são do tipo SYN Flooding attack.

III. O TCP transmite dados em modo half-duplex e o estabelecimento de conexão é denominado three-way handshaking.

Está correto somente o que se afirma em:

Com relação ao arquivo AndroidManifest.xml de um projeto criado no Android Studio, analise as afirmativas a seguir:

I. É a base de uma aplicação Android. Ele é obrigatório e deve ficar na mesma pasta raiz do projeto e contém todas as configurações necessárias para a execução da aplicação.

II. É obrigatório que cada Activity do projeto esteja declarada, caso contrário não será possível utilizá-la.

III. A primeira linha do arquivo é a tag <Manifest> que declara o pacote principal do projeto.

Está correto somente o que se afirma em:

Com relação aos arquivos XAML do framework .NET produzidos pela IDE do Visual Studio durante o processo de desenvolvimento de uma aplicação móvel para o Windows Phone 8.1, analise as afirmativas a seguir:

I. Um arquivo XAML deve ter mais de um elemento raiz.

II. Window, Page, ResourceDictionary e Application são elementos do tipo raiz.

III. O namespace padrão do WPF é o http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation.

Está correto somente o que se afirma em:

João foi incumbido de rever um lote de consultas SQL. Como ainda é iniciante nesse assunto, João solicitou ajuda ao colega que lhe pareceu ser o mais experiente, e recebeu as seguintes recomendações gerais:

I. use a cláusula DISTINCT somente quando estritamente necessária;

II. dê preferência às junções externas (LEFT, RIGHT, OUTER) em relação às internas (INNER);

III. use subconsultas escalares no comando SELECT, tais como “SELECT x,y,(SELECT ...) z ..." sempre que possível.

Sobre essas recomendações, é correto afirmar que:

No PostGreSQL, a linguagem PL/pgSQL pode ser utilizada para definir procedures que são executadas como triggers, quando várias “special variables” são criadas, no escopo do bloco mais externo, e tornam-se disponíveis para uso no código da procedure.

Nesse contexto, analise as seguintes afirmativas sobre algumas dessas variáveis e o funcionamento de triggers no PostgreSQL:

I. A variável NEW contém um valor booleano que indica se o registro objeto do trigger está sendo incluído (true) ou não (false).

II. A variável NEW contém os campos de um registro que está sendo incluído (insert) ou alterado (update).

III. A variável TG_OP contém uma string que determina o nome da operação que desencadeou o trigger (insert, update, etc.).

IV. Na declaração de um trigger, as opções FOR EACH ROW e FOR EACH STATEMENT são equivalentes, tendo sido mantidas apenas para efeito de compatibilidade com versões anteriores.

Está correto somente o que se afirma em:

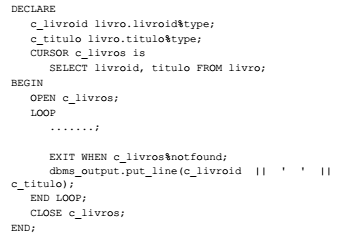

Analise o scritpt Oracle PL/SQL a seguir:

Para que esse script funcione corretamente, exibindo os códigos identificadores e títulos de cada livro, a linha pontilhada deve ser substituída por:

Algumas das mais importantes implementações de bancos de dados relacionais dispõem do comando TRUNCATE para remover registros de uma tabela.

Considere as seguintes opções para remover registros de uma tabela T:

I. Usando o comando DELETE;

II. Usando o comando TRUNCATE;

III. Removendo a tabela T e executando um comando CREATE TABLE para recriá-la em seguida.

Sobre essas opções, é correto afirmar que:

Atenção:

Algumas das questões seguintes fazem referência a um banco de

dados relacional intitulado BOOKS, cujas tabelas e respectivas

instâncias são exibidas a seguir. Essas questões referem-se às

instâncias mostradas.

A tabela Livro representa livros. Cada livro tem um autor, representado na tabela Autor. A tabela Oferta representa os livros que são ofertados pelas livrarias, estas representadas pela tabela Livraria. NULL significa um campo não preenchido.

AutorID, LivrariaID e LivroID, respectivamente, constituem as chaves primárias das tabelas Autor, Livraria e Livro.

LivrariaID e LivroID constituem a chave primária da tabela Oferta.

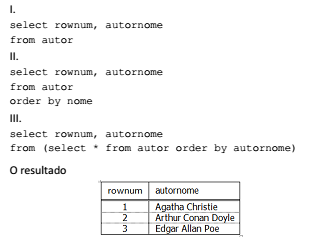

Considere uma implementação Oracle do banco BOOKS.

para qualquer que tenha sido a ordem de inclusão dos registros

na tabela, pode ser obtido somente pelo(s) comando(s):

Atenção:

Algumas das questões seguintes fazem referência a um banco de dados relacional intitulado BOOKS, cujas tabelas e respectivas instâncias são exibidas a seguir. Essas questões referem-se às instâncias mostradas.

A tabela Livro representa livros. Cada livro tem um autor, representado na tabela Autor. A tabela Oferta representa os livros que são ofertados pelas livrarias, estas representadas pela tabela Livraria. NULL significa um campo não preenchido.

AutorID, LivrariaID e LivroID, respectivamente, constituem as chaves primárias das tabelas Autor, Livraria e Livro.

LivrariaID e LivroID constituem a chave primária da tabela Oferta.

No banco de dados BOOKS, o campo NumLivrarias, da tabela Livro, contém informação redundante, pois denota o número de livrarias que oferecem o livro e pode ser computado.

O comando SQL que calcula e atualiza esse campo corretamente é:

Atenção:

Algumas das questões seguintes fazem referência a um banco de dados relacional intitulado BOOKS, cujas tabelas e respectivas instâncias são exibidas a seguir. Essas questões referem-se às instâncias mostradas.

A tabela Livro representa livros. Cada livro tem um autor, representado na tabela Autor. A tabela Oferta representa os livros que são ofertados pelas livrarias, estas representadas pela tabela Livraria. NULL significa um campo não preenchido.

AutorID, LivrariaID e LivroID, respectivamente, constituem as chaves primárias das tabelas Autor, Livraria e Livro.

LivrariaID e LivroID constituem a chave primária da tabela Oferta.

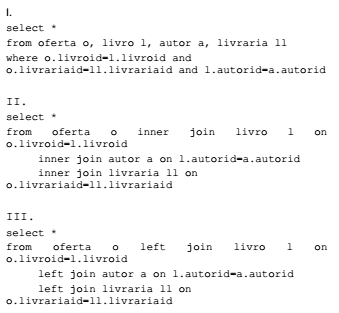

Com relação ao banco de dados BOOKS, analise os comandos SQL exibidos a seguir:

É correto afirmar que:

Sobre os amigos Marcos, Renato e Waldo, sabe-se que:

I - Se Waldo é flamenguista, então Marcos não é tricolor;

II - Se Renato não é vascaíno, então Marcos é tricolor;

III - Se Renato é vascaíno, então Waldo não é flamenguista.

Logo, deduz-se que:

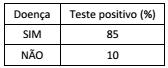

De um grupo de controle para o acompanhamento de uma determinada doença, 4% realmente têm a doença. A tabela a seguir mostra as porcentagens das pessoas que têm e das que não têm a doença e que apresentaram resultado positivo em um determinado teste.

Entre as pessoas desse grupo que apresentaram resultado

positivo no teste, a porcentagem daquelas que realmente têm a

doença é aproximadamente:

Em uma caixa há doze dúzias de laranjas, sobre as quais sabe-se que:

I - há pelo menos duas laranjas estragadas;

II - dadas seis quaisquer dessas laranjas, há pelo menos duas não estragadas.

Sobre essas doze dúzias de laranjas, deduz-se que:

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)