Questões de Concurso

Para sead-ap

Foram encontradas 1.931 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

( ) The concept of critical literacy lacks precise definition.

( ) Functional and critical literacies have similar aims.

( ) Classroom practices based on critical literacy vary.

The statements are, respectively:

CAMPOS, L., CANAVEZES, S. Introdução à Globalização. Instituto Bento Jesus Caraça. CGTP. 2007

Sobre o processo de globalização, assinale a afirmativa correta.

As fronteiras delimitam os territórios e foram instrumentalizadas pelo poder político como linhas de ruptura, principalmente a partir da constituição dos Estados-nação na Europa Ocidental.

A partir da 2ª Guerra Mundial, as fronteiras sofreram significativas mudanças. Sobre essas mudanças, analise as afirmativas a seguir.

I. A ideia de fronteira e suas representações evoluiu a partir da intensificação dos fluxos eletrônicos. II. A “cortina de ferro”, a linha de ruptura que separou dois blocos, foi definida a partir de doutrinas econômicas e ideológicas opostas. III. O conceito de fronteira como linha de ruptura foi abalado à medida que se desenvolveu a construção da unidade europeia.

Está correto o que se afirma em

Sobre as condições que dificultaram a integração dos países latino-americanos, assinale a afirmativa correta.

MAGNOLI, Demétrio. Geografia para o Ensino Médio. Ed. Atual. São Paulo. 2012. (Adaptado)

Sobre os ciclos da economia capitalista, assinale a afirmativa incorreta.

Sobre o quadro geopolítico atual, assinale a afirmativa correta.

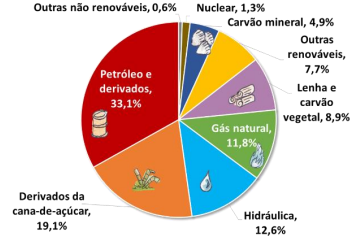

Matriz Energética Brasileira (2020)

Empresa de Pesquisa Energética - EPE – epe.gov.br. Acesso em 27/09/2022.

Assinale a opção que não apresenta uma razão para esse declínio.

Sobre os tecnopolos, assinale a afirmativa incorreta.

SANTOS, Milton. A urbanização brasileira. Ed. HUCITEC. São Paulo. 1995. (Adaptado)

Sobre os problemas das cidades brasileiras, assinale a afirmativa incorreta.

( ) Entre os anos 1950 e 1980, a economia brasileira cresceu a uma taxa média de 7% ao ano e consolidou a transição da economia tipicamente primário-exportadora para a urbanoindustrial. ( ) Desde os anos 1980, a economia brasileira vem apresentando um ciclo de baixo nível de crescimento, uma redução da taxa de investimento e a diminuição da presença do Estado como agente coordenador do desenvolvimento. ( ) Nos anos 1990, a economia brasileira ficou marcada pelas reformas neoliberais, com a abertura comercial e financeira, as privatizações, a desnacionalização do parque industrial e a reforma gerencial do Estado.

As afirmativas são, na ordem apresentada, respectivamente,

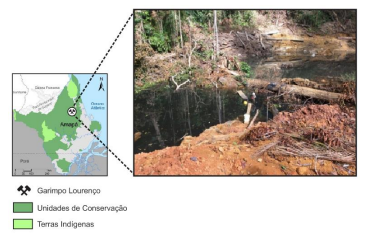

Sobre a região garimpeira do Lourenço (mapa e foto), analise as afirmativas a seguir.

I. Os planos de manejo das unidades de conservação de proteção integral mencionam o garimpo do Lourenço como uma ameaça à integridade dos ecossistemas e à biodiversidade. II. A existência de um conjunto de áreas protegidas no Norte do Amapá e na Guiana Francesa deslocou o garimpo do Lourenço para uma condição geopolítica muito delicada. III. O garimpo do Lourenço, situado entre as cabeceiras do rio Araguari e as do rio Oiapoque, pode ser criminalizado pela contaminação mercurial constatada nos rios dessas bacias.

Está correto o que se afirma em

I. surgiram Os centros urbanos multifuncionais que surgiram nas áreas de agricultura empresarial conectam-se às áreas dinâmicas do país graças aos recursos das comunicações modernas. II. Manaus consolidou sua vocação como polo industrial sob o amparo da regulação especial da Zona Franca, com destaque para as indústrias eletroeletrônica e mecânica. III. Macapá tornou-se referência para prover a população local e/ou regional devido à disponibilidade de bens de consumo duráveis e não duráveis e à infraestrutura de serviços de educação, saúde e segurança.

Está correto o que se afirma em