Questões de Concurso

Para analista do banco central - área 2

Foram encontradas 105 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

O conceito acima refere-se ao paradigma

Quadro 1 – Categoria de Atributo

I. Atributo do Produto II. Atributo do Hardware III. Atributo de Pessoal IV. Atributo de Projeto

Quadro 2 – Atributo Direcionador de Custo

1. Confiabilidade exigida do software 2. Tamanho do banco de dados da aplicação 3. Capacidade de engenharia de software 4. Uso de ferramentas de software 5. Cronograma de atividades de desenvolvimento exigido

A correta associação entre os elementos das duas tabelas é

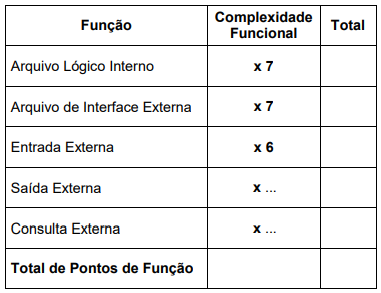

Considere a tabela abaixo (parcialmente preenchida), para cálculo de pontos de função:

Sabendo que a complexidade funcional (Simples, Média e

Complexa) é determinada em função da quantidade de

registros e/ou arquivos lógicos e itens de dados

referenciados, é correto afirmar que, aos totais atribuídos

a Arquivo Lógico Interno, Arquivo de Interface Externa e

Entrada Externa, correspondem, respectivamente, as

classificações

Em um SGBD, em que a separação entre os níveis conceitual e interno são bem claras, é utilizada a linguagem ....I.... , para a especificação do esquema interno. Onde a separação entre os níveis interno e conceitual não é muito clara, o SGBD possui um compilador que permite a execução das declarações para identificar as descrições dos esquemas e para armazená-las no catálogo. Neste caso utiliza-se a ....II.... . No SGBD, cuja arquitetura utiliza os esquemas conceitual, interno e externo, é necessária a adoção da ....III.... .

Preenchem correta e respectivamente as lacunas I, II e III: