Questões de Concurso

Para engenheiro de manutenção pleno - mecânica

Foram encontradas 60 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

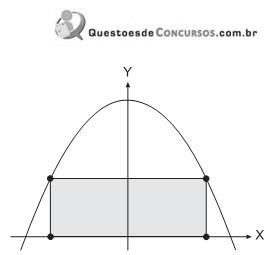

Dentre os valores abaixo, aquele que mais se aproxima da área máxima desse retângulo é

Se laranja é uma das frutas disponíveis e se o pedido é de uma “vitamina caótica", a probabilidade de que a vitamina contenha laranja é

é

é

Written by Laura Hill

Water and oil don’t mix. We see this every day; just try washing olive oil off your hands without soap or washing your face in the morning with only water. It just doesn’t work!

When an oil spill occurs in the ocean, like the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what do scientists do to clean up the toxic mess? There are a number of options for an oil spill cleanup and most efforts use a combination of many techniques. The fact that oil and water don’t mix is a blessing and a curse. If oil mixed with water, it would be difficult to divide the two.

Crude oil is less dense than water; it spreads out to make a very thin layer (about one millimetre thick) that floats on top of the water. This is good because we can tell what is water and what is oil. It is also bad, because it means the oil can spread really quickly and cover a very large area, which becomes difficult to manage. Combined with wind, ocean currents and waves, oil spill cleanup starts to get really tricky.

Chemical dispersants can be used to break up big oil slicks into small oil droplets. They work like soaps by emulsifying the hydrophobic (waterrepelling) oil in the water. These small droplets can degrade in the ecosystem quicker than the big oil slick. But unfortunately, this means that marine life of all sizes ingest these toxic, broken-down particles and chemicals.

If the oil is thick enough, it could be set fire, a process called “in situ burning”. Because the oil is highly flammable and floats on top of the water, it is very easy to set it alight. It’s not environmentallyfriendly though; the combustion of oil releases thick smoke that contains greenhouse gases and other dangerous air pollutants.

Some techniques can contain and recapture spilled oil without changing its chemical composition. Booms float on top of the water and act as barriers to the movement of oil. Once the oil is controlled, it can be gathered using sorbents. “Sorbent” is a fancy word for sponge. These sponges absorb the oil and allow it to be collected by siphoning it off the water.

However, weather and sea conditions can prevent and obstruct the use of booms, sorbents and in situ burning. Imagine trying to perform these operations on the open sea with wind, waves and water currents moving the oil (and your boat!) around on the water.

What about the plants and animals? It’s easy to forget about the organisms in the sea that are under water. Out of sight, out of mind! There is not much we can do to help them. But when oil reaches the shore it impacts sensitive coastal environments including the many fish, bird, amphibian, reptilian, and crustaceanspecies that live there. We have easy access to these areas and there are some things we can do to clean up. For the plants, it is often a matter of setting them on fire, or leaving them to degrade the oil naturally. Sometimes, we can spray the oil with nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that can encourage the growth of specialized microorganisms. For species that can tolerate our soaps, manpower is needed to wash every affected animal. Yet, if the animal has tried to lick itself clean, it can die from ingesting the toxic oil.

Unfortunately, there can be many negative economic and social impacts, in addition to the environmental impacts of oil spills and, as you’ve just read, the clean up techniques are far from perfect. Prevention is the very best cleanup technique we have. http://www.curiocity.ca/everyday-science/environme... -cleaning-up-a-spill.html, retrieved on Dec 10, 2010

Written by Laura Hill

Water and oil don’t mix. We see this every day; just try washing olive oil off your hands without soap or washing your face in the morning with only water. It just doesn’t work!

When an oil spill occurs in the ocean, like the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what do scientists do to clean up the toxic mess? There are a number of options for an oil spill cleanup and most efforts use a combination of many techniques. The fact that oil and water don’t mix is a blessing and a curse. If oil mixed with water, it would be difficult to divide the two.

Crude oil is less dense than water; it spreads out to make a very thin layer (about one millimetre thick) that floats on top of the water. This is good because we can tell what is water and what is oil. It is also bad, because it means the oil can spread really quickly and cover a very large area, which becomes difficult to manage. Combined with wind, ocean currents and waves, oil spill cleanup starts to get really tricky.

Chemical dispersants can be used to break up big oil slicks into small oil droplets. They work like soaps by emulsifying the hydrophobic (waterrepelling) oil in the water. These small droplets can degrade in the ecosystem quicker than the big oil slick. But unfortunately, this means that marine life of all sizes ingest these toxic, broken-down particles and chemicals.

If the oil is thick enough, it could be set fire, a process called “in situ burning”. Because the oil is highly flammable and floats on top of the water, it is very easy to set it alight. It’s not environmentallyfriendly though; the combustion of oil releases thick smoke that contains greenhouse gases and other dangerous air pollutants.

Some techniques can contain and recapture spilled oil without changing its chemical composition. Booms float on top of the water and act as barriers to the movement of oil. Once the oil is controlled, it can be gathered using sorbents. “Sorbent” is a fancy word for sponge. These sponges absorb the oil and allow it to be collected by siphoning it off the water.

However, weather and sea conditions can prevent and obstruct the use of booms, sorbents and in situ burning. Imagine trying to perform these operations on the open sea with wind, waves and water currents moving the oil (and your boat!) around on the water.

What about the plants and animals? It’s easy to forget about the organisms in the sea that are under water. Out of sight, out of mind! There is not much we can do to help them. But when oil reaches the shore it impacts sensitive coastal environments including the many fish, bird, amphibian, reptilian, and crustaceanspecies that live there. We have easy access to these areas and there are some things we can do to clean up. For the plants, it is often a matter of setting them on fire, or leaving them to degrade the oil naturally. Sometimes, we can spray the oil with nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that can encourage the growth of specialized microorganisms. For species that can tolerate our soaps, manpower is needed to wash every affected animal. Yet, if the animal has tried to lick itself clean, it can die from ingesting the toxic oil.

Unfortunately, there can be many negative economic and social impacts, in addition to the environmental impacts of oil spills and, as you’ve just read, the clean up techniques are far from perfect. Prevention is the very best cleanup technique we have. http://www.curiocity.ca/everyday-science/environme... -cleaning-up-a-spill.html, retrieved on Dec 10, 2010

Written by Laura Hill

Water and oil don’t mix. We see this every day; just try washing olive oil off your hands without soap or washing your face in the morning with only water. It just doesn’t work!

When an oil spill occurs in the ocean, like the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what do scientists do to clean up the toxic mess? There are a number of options for an oil spill cleanup and most efforts use a combination of many techniques. The fact that oil and water don’t mix is a blessing and a curse. If oil mixed with water, it would be difficult to divide the two.

Crude oil is less dense than water; it spreads out to make a very thin layer (about one millimetre thick) that floats on top of the water. This is good because we can tell what is water and what is oil. It is also bad, because it means the oil can spread really quickly and cover a very large area, which becomes difficult to manage. Combined with wind, ocean currents and waves, oil spill cleanup starts to get really tricky.

Chemical dispersants can be used to break up big oil slicks into small oil droplets. They work like soaps by emulsifying the hydrophobic (waterrepelling) oil in the water. These small droplets can degrade in the ecosystem quicker than the big oil slick. But unfortunately, this means that marine life of all sizes ingest these toxic, broken-down particles and chemicals.

If the oil is thick enough, it could be set fire, a process called “in situ burning”. Because the oil is highly flammable and floats on top of the water, it is very easy to set it alight. It’s not environmentallyfriendly though; the combustion of oil releases thick smoke that contains greenhouse gases and other dangerous air pollutants.

Some techniques can contain and recapture spilled oil without changing its chemical composition. Booms float on top of the water and act as barriers to the movement of oil. Once the oil is controlled, it can be gathered using sorbents. “Sorbent” is a fancy word for sponge. These sponges absorb the oil and allow it to be collected by siphoning it off the water.

However, weather and sea conditions can prevent and obstruct the use of booms, sorbents and in situ burning. Imagine trying to perform these operations on the open sea with wind, waves and water currents moving the oil (and your boat!) around on the water.

What about the plants and animals? It’s easy to forget about the organisms in the sea that are under water. Out of sight, out of mind! There is not much we can do to help them. But when oil reaches the shore it impacts sensitive coastal environments including the many fish, bird, amphibian, reptilian, and crustaceanspecies that live there. We have easy access to these areas and there are some things we can do to clean up. For the plants, it is often a matter of setting them on fire, or leaving them to degrade the oil naturally. Sometimes, we can spray the oil with nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that can encourage the growth of specialized microorganisms. For species that can tolerate our soaps, manpower is needed to wash every affected animal. Yet, if the animal has tried to lick itself clean, it can die from ingesting the toxic oil.

Unfortunately, there can be many negative economic and social impacts, in addition to the environmental impacts of oil spills and, as you’ve just read, the clean up techniques are far from perfect. Prevention is the very best cleanup technique we have. http://www.curiocity.ca/everyday-science/environme... -cleaning-up-a-spill.html, retrieved on Dec 10, 2010

Written by Laura Hill

Water and oil don’t mix. We see this every day; just try washing olive oil off your hands without soap or washing your face in the morning with only water. It just doesn’t work!

When an oil spill occurs in the ocean, like the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what do scientists do to clean up the toxic mess? There are a number of options for an oil spill cleanup and most efforts use a combination of many techniques. The fact that oil and water don’t mix is a blessing and a curse. If oil mixed with water, it would be difficult to divide the two.

Crude oil is less dense than water; it spreads out to make a very thin layer (about one millimetre thick) that floats on top of the water. This is good because we can tell what is water and what is oil. It is also bad, because it means the oil can spread really quickly and cover a very large area, which becomes difficult to manage. Combined with wind, ocean currents and waves, oil spill cleanup starts to get really tricky.

Chemical dispersants can be used to break up big oil slicks into small oil droplets. They work like soaps by emulsifying the hydrophobic (waterrepelling) oil in the water. These small droplets can degrade in the ecosystem quicker than the big oil slick. But unfortunately, this means that marine life of all sizes ingest these toxic, broken-down particles and chemicals.

If the oil is thick enough, it could be set fire, a process called “in situ burning”. Because the oil is highly flammable and floats on top of the water, it is very easy to set it alight. It’s not environmentallyfriendly though; the combustion of oil releases thick smoke that contains greenhouse gases and other dangerous air pollutants.

Some techniques can contain and recapture spilled oil without changing its chemical composition. Booms float on top of the water and act as barriers to the movement of oil. Once the oil is controlled, it can be gathered using sorbents. “Sorbent” is a fancy word for sponge. These sponges absorb the oil and allow it to be collected by siphoning it off the water.

However, weather and sea conditions can prevent and obstruct the use of booms, sorbents and in situ burning. Imagine trying to perform these operations on the open sea with wind, waves and water currents moving the oil (and your boat!) around on the water.

What about the plants and animals? It’s easy to forget about the organisms in the sea that are under water. Out of sight, out of mind! There is not much we can do to help them. But when oil reaches the shore it impacts sensitive coastal environments including the many fish, bird, amphibian, reptilian, and crustaceanspecies that live there. We have easy access to these areas and there are some things we can do to clean up. For the plants, it is often a matter of setting them on fire, or leaving them to degrade the oil naturally. Sometimes, we can spray the oil with nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that can encourage the growth of specialized microorganisms. For species that can tolerate our soaps, manpower is needed to wash every affected animal. Yet, if the animal has tried to lick itself clean, it can die from ingesting the toxic oil.

Unfortunately, there can be many negative economic and social impacts, in addition to the environmental impacts of oil spills and, as you’ve just read, the clean up techniques are far from perfect. Prevention is the very best cleanup technique we have. http://www.curiocity.ca/everyday-science/environme... -cleaning-up-a-spill.html, retrieved on Dec 10, 2010

Written by Laura Hill

Water and oil don’t mix. We see this every day; just try washing olive oil off your hands without soap or washing your face in the morning with only water. It just doesn’t work!

When an oil spill occurs in the ocean, like the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what do scientists do to clean up the toxic mess? There are a number of options for an oil spill cleanup and most efforts use a combination of many techniques. The fact that oil and water don’t mix is a blessing and a curse. If oil mixed with water, it would be difficult to divide the two.

Crude oil is less dense than water; it spreads out to make a very thin layer (about one millimetre thick) that floats on top of the water. This is good because we can tell what is water and what is oil. It is also bad, because it means the oil can spread really quickly and cover a very large area, which becomes difficult to manage. Combined with wind, ocean currents and waves, oil spill cleanup starts to get really tricky.

Chemical dispersants can be used to break up big oil slicks into small oil droplets. They work like soaps by emulsifying the hydrophobic (waterrepelling) oil in the water. These small droplets can degrade in the ecosystem quicker than the big oil slick. But unfortunately, this means that marine life of all sizes ingest these toxic, broken-down particles and chemicals.

If the oil is thick enough, it could be set fire, a process called “in situ burning”. Because the oil is highly flammable and floats on top of the water, it is very easy to set it alight. It’s not environmentallyfriendly though; the combustion of oil releases thick smoke that contains greenhouse gases and other dangerous air pollutants.

Some techniques can contain and recapture spilled oil without changing its chemical composition. Booms float on top of the water and act as barriers to the movement of oil. Once the oil is controlled, it can be gathered using sorbents. “Sorbent” is a fancy word for sponge. These sponges absorb the oil and allow it to be collected by siphoning it off the water.

However, weather and sea conditions can prevent and obstruct the use of booms, sorbents and in situ burning. Imagine trying to perform these operations on the open sea with wind, waves and water currents moving the oil (and your boat!) around on the water.

What about the plants and animals? It’s easy to forget about the organisms in the sea that are under water. Out of sight, out of mind! There is not much we can do to help them. But when oil reaches the shore it impacts sensitive coastal environments including the many fish, bird, amphibian, reptilian, and crustaceanspecies that live there. We have easy access to these areas and there are some things we can do to clean up. For the plants, it is often a matter of setting them on fire, or leaving them to degrade the oil naturally. Sometimes, we can spray the oil with nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that can encourage the growth of specialized microorganisms. For species that can tolerate our soaps, manpower is needed to wash every affected animal. Yet, if the animal has tried to lick itself clean, it can die from ingesting the toxic oil.

Unfortunately, there can be many negative economic and social impacts, in addition to the environmental impacts of oil spills and, as you’ve just read, the clean up techniques are far from perfect. Prevention is the very best cleanup technique we have. http://www.curiocity.ca/everyday-science/environme... -cleaning-up-a-spill.html, retrieved on Dec 10, 2010

Considerando o desfecho da história, a mensagem que a tira veicula é:

A minha alma está armada

E apontada para a cara do

Sossego

Pois paz sem voz

Não é paz é medo

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

Qual a paz que eu não

Quero conservar

Para tentar ser feliz

As grades do condomínio

São para trazer proteção

Mas também trazem a dúvida

Se é você que está nesta prisão

Me abrace e me dê um beijo

Faça um filho comigo

Mas não me deixe sentar

Na poltrona no dia de domingo

Procurando novas drogas de aluguel

Nesse vídeo coagido pela paz

Que eu não quero seguir admitido

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

YUKA, Marcelo / O Rappa. CD Lado B Lado A. WEA, 1999.

Às vezes é ela quem diz" (v. 6-7)

Considere as afirmações abaixo acerca do emprego do sinal indicativo de crase nos trechos destacados acima.

I - O uso do acento grave está correto porque se trata de uma expressão adverbial com núcleo feminino sem ideia de instrumento

II - O acento grave, nessa expressão, é facultativo, pois existem casos em que o substantivo “vezes" aparece como sujeito.

III - Não ocorre o fenômeno da crase nesse trecho, uma vez que, nessa expressão, o vocábulo “vezes" aparece como substantivo.

É correto APENAS o que se afirma em

A minha alma está armada

E apontada para a cara do

Sossego

Pois paz sem voz

Não é paz é medo

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

Qual a paz que eu não

Quero conservar

Para tentar ser feliz

As grades do condomínio

São para trazer proteção

Mas também trazem a dúvida

Se é você que está nesta prisão

Me abrace e me dê um beijo

Faça um filho comigo

Mas não me deixe sentar

Na poltrona no dia de domingo

Procurando novas drogas de aluguel

Nesse vídeo coagido pela paz

Que eu não quero seguir admitido

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

YUKA, Marcelo / O Rappa. CD Lado B Lado A. WEA, 1999.

E apontada para a cara do

Sossego

Pois paz sem voz

Não é paz é medo" (v. 1-5)

A palavra “sossego", no texto, não apresenta um valor positivo. Sem prejuízo para a mensagem da letra da música, esse vocábulo pode ser substituído por

A minha alma está armada

E apontada para a cara do

Sossego

Pois paz sem voz

Não é paz é medo

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

Qual a paz que eu não

Quero conservar

Para tentar ser feliz

As grades do condomínio

São para trazer proteção

Mas também trazem a dúvida

Se é você que está nesta prisão

Me abrace e me dê um beijo

Faça um filho comigo

Mas não me deixe sentar

Na poltrona no dia de domingo

Procurando novas drogas de aluguel

Nesse vídeo coagido pela paz

Que eu não quero seguir admitido

Às vezes eu falo com a vida

Às vezes é ela quem diz

YUKA, Marcelo / O Rappa. CD Lado B Lado A. WEA, 1999.

Considerando a passagem transcrita acima, analise as afirmações a seguir.

A colocação do pronome destacado no verso transcrito está adequada à norma padrão da Língua Portuguesa.

PORQUE

A palavra “não", advérbio de negação, exige que o pronome oblíquo esteja em posição proclítica.

A esse respeito, conclui-se que

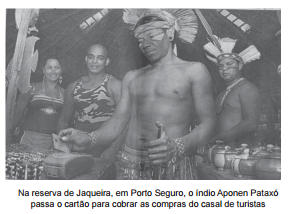

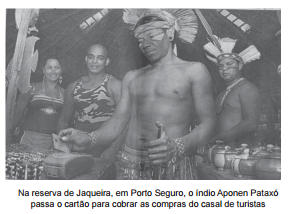

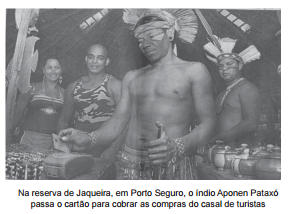

SURPRESA NA ENTRADA DA ALDEIA

Retornando à Reserva Indígena de Jaqueira, no extremo sul da Bahia, a turista Tânia Mara Scavello disse ter se surpreendido, já na portaria, ao ver a placa indicativa de aceitação de cartões de crédito. Essa é a reação mais comum de quem procura a reserva para comprar artesanato, de acordo com o índio pataxó Juraci, vice-presidente da Associação Pataxó de Ecoturismo.

– Há tantos lugares que não aceitam, e aqui já estão se modernizando – disse Tânia, cliente do índio Camaiurá, que foi à reserva com o marido, o italiano Mário Scavello, para levar um casal de amigos. Scavello considera positiva a implantação do sistema na aldeia:

– Eles já sobrevivem da tradição, está certo desfrutarem um pouco da tecnologia para ganhar dinheiro. Para o casal de turistas paulistas, Fabrício Lisboa e Camila Rodrigues, pela primeira vez na reserva, a disponibilidade do sistema também surpreendeu:

– Fiquei surpresa pelo fato de estar numa aldeia e ter o privilégio de poder contar com a modernização – disse Camila, que comprou peças do índio Aponen.

Implantado há mais de um mês, o cartão impulsionou as vendas locais.

– Outro dia, veio um turista e separou um monte de artesanato. Só levou tudo porque aceitamos cartão. Eles andam com pouco dinheiro. – contou a índia Mitynawã.

As peças de artesanato, produzidas com sementes e coco, variam de R$ 5 a R$ 15. Outra fonte de renda é o valor do ingresso, que custa R$ 35:

– Não somos assalariados, todo mundo é voluntário. A venda do artesanato é uma alternativa de sobrevivência, pois não caçamos mais, e a implantação do cartão colabora para o aumento da nossa renda. O Globo, 26 ago. 2008. (Adaptado)

Quanto à sintaxe de regência, o trecho que apresenta um verbo com regência semelhante à do termo destacado na passagem transcrita acima é:

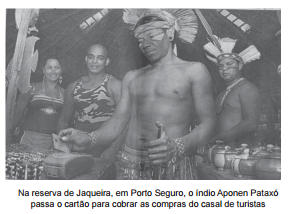

SURPRESA NA ENTRADA DA ALDEIA

Retornando à Reserva Indígena de Jaqueira, no extremo sul da Bahia, a turista Tânia Mara Scavello disse ter se surpreendido, já na portaria, ao ver a placa indicativa de aceitação de cartões de crédito. Essa é a reação mais comum de quem procura a reserva para comprar artesanato, de acordo com o índio pataxó Juraci, vice-presidente da Associação Pataxó de Ecoturismo.

– Há tantos lugares que não aceitam, e aqui já estão se modernizando – disse Tânia, cliente do índio Camaiurá, que foi à reserva com o marido, o italiano Mário Scavello, para levar um casal de amigos. Scavello considera positiva a implantação do sistema na aldeia:

– Eles já sobrevivem da tradição, está certo desfrutarem um pouco da tecnologia para ganhar dinheiro. Para o casal de turistas paulistas, Fabrício Lisboa e Camila Rodrigues, pela primeira vez na reserva, a disponibilidade do sistema também surpreendeu:

– Fiquei surpresa pelo fato de estar numa aldeia e ter o privilégio de poder contar com a modernização – disse Camila, que comprou peças do índio Aponen.

Implantado há mais de um mês, o cartão impulsionou as vendas locais.

– Outro dia, veio um turista e separou um monte de artesanato. Só levou tudo porque aceitamos cartão. Eles andam com pouco dinheiro. – contou a índia Mitynawã.

As peças de artesanato, produzidas com sementes e coco, variam de R$ 5 a R$ 15. Outra fonte de renda é o valor do ingresso, que custa R$ 35:

– Não somos assalariados, todo mundo é voluntário. A venda do artesanato é uma alternativa de sobrevivência, pois não caçamos mais, e a implantação do cartão colabora para o aumento da nossa renda. O Globo, 26 ago. 2008. (Adaptado)

No trecho transcrito acima, o uso da vírgula no período justifica-se porque

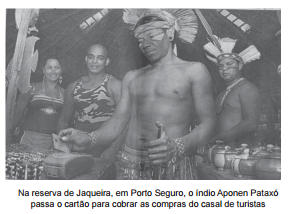

SURPRESA NA ENTRADA DA ALDEIA

Retornando à Reserva Indígena de Jaqueira, no extremo sul da Bahia, a turista Tânia Mara Scavello disse ter se surpreendido, já na portaria, ao ver a placa indicativa de aceitação de cartões de crédito. Essa é a reação mais comum de quem procura a reserva para comprar artesanato, de acordo com o índio pataxó Juraci, vice-presidente da Associação Pataxó de Ecoturismo.

– Há tantos lugares que não aceitam, e aqui já estão se modernizando – disse Tânia, cliente do índio Camaiurá, que foi à reserva com o marido, o italiano Mário Scavello, para levar um casal de amigos. Scavello considera positiva a implantação do sistema na aldeia:

– Eles já sobrevivem da tradição, está certo desfrutarem um pouco da tecnologia para ganhar dinheiro. Para o casal de turistas paulistas, Fabrício Lisboa e Camila Rodrigues, pela primeira vez na reserva, a disponibilidade do sistema também surpreendeu:

– Fiquei surpresa pelo fato de estar numa aldeia e ter o privilégio de poder contar com a modernização – disse Camila, que comprou peças do índio Aponen.

Implantado há mais de um mês, o cartão impulsionou as vendas locais.

– Outro dia, veio um turista e separou um monte de artesanato. Só levou tudo porque aceitamos cartão. Eles andam com pouco dinheiro. – contou a índia Mitynawã.

As peças de artesanato, produzidas com sementes e coco, variam de R$ 5 a R$ 15. Outra fonte de renda é o valor do ingresso, que custa R$ 35:

– Não somos assalariados, todo mundo é voluntário. A venda do artesanato é uma alternativa de sobrevivência, pois não caçamos mais, e a implantação do cartão colabora para o aumento da nossa renda. O Globo, 26 ago. 2008. (Adaptado)

No trecho transcrito acima, a oração destacada, apesar de não apresentar conectivo, liga-se à primeira com determinada relação de sentido.

Essa relação de sentido é caracterizada por uma ideia de

SURPRESA NA ENTRADA DA ALDEIA

Retornando à Reserva Indígena de Jaqueira, no extremo sul da Bahia, a turista Tânia Mara Scavello disse ter se surpreendido, já na portaria, ao ver a placa indicativa de aceitação de cartões de crédito. Essa é a reação mais comum de quem procura a reserva para comprar artesanato, de acordo com o índio pataxó Juraci, vice-presidente da Associação Pataxó de Ecoturismo.

– Há tantos lugares que não aceitam, e aqui já estão se modernizando – disse Tânia, cliente do índio Camaiurá, que foi à reserva com o marido, o italiano Mário Scavello, para levar um casal de amigos. Scavello considera positiva a implantação do sistema na aldeia:

– Eles já sobrevivem da tradição, está certo desfrutarem um pouco da tecnologia para ganhar dinheiro. Para o casal de turistas paulistas, Fabrício Lisboa e Camila Rodrigues, pela primeira vez na reserva, a disponibilidade do sistema também surpreendeu:

– Fiquei surpresa pelo fato de estar numa aldeia e ter o privilégio de poder contar com a modernização – disse Camila, que comprou peças do índio Aponen.

Implantado há mais de um mês, o cartão impulsionou as vendas locais.

– Outro dia, veio um turista e separou um monte de artesanato. Só levou tudo porque aceitamos cartão. Eles andam com pouco dinheiro. – contou a índia Mitynawã.

As peças de artesanato, produzidas com sementes e coco, variam de R$ 5 a R$ 15. Outra fonte de renda é o valor do ingresso, que custa R$ 35:

– Não somos assalariados, todo mundo é voluntário. A venda do artesanato é uma alternativa de sobrevivência, pois não caçamos mais, e a implantação do cartão colabora para o aumento da nossa renda. O Globo, 26 ago. 2008. (Adaptado)

SURPRESA NA ENTRADA DA ALDEIA

Retornando à Reserva Indígena de Jaqueira, no extremo sul da Bahia, a turista Tânia Mara Scavello disse ter se surpreendido, já na portaria, ao ver a placa indicativa de aceitação de cartões de crédito. Essa é a reação mais comum de quem procura a reserva para comprar artesanato, de acordo com o índio pataxó Juraci, vice-presidente da Associação Pataxó de Ecoturismo.

– Há tantos lugares que não aceitam, e aqui já estão se modernizando – disse Tânia, cliente do índio Camaiurá, que foi à reserva com o marido, o italiano Mário Scavello, para levar um casal de amigos. Scavello considera positiva a implantação do sistema na aldeia:

– Eles já sobrevivem da tradição, está certo desfrutarem um pouco da tecnologia para ganhar dinheiro. Para o casal de turistas paulistas, Fabrício Lisboa e Camila Rodrigues, pela primeira vez na reserva, a disponibilidade do sistema também surpreendeu:

– Fiquei surpresa pelo fato de estar numa aldeia e ter o privilégio de poder contar com a modernização – disse Camila, que comprou peças do índio Aponen.

Implantado há mais de um mês, o cartão impulsionou as vendas locais.

– Outro dia, veio um turista e separou um monte de artesanato. Só levou tudo porque aceitamos cartão. Eles andam com pouco dinheiro. – contou a índia Mitynawã.

As peças de artesanato, produzidas com sementes e coco, variam de R$ 5 a R$ 15. Outra fonte de renda é o valor do ingresso, que custa R$ 35:

– Não somos assalariados, todo mundo é voluntário. A venda do artesanato é uma alternativa de sobrevivência, pois não caçamos mais, e a implantação do cartão colabora para o aumento da nossa renda. O Globo, 26 ago. 2008. (Adaptado)