Questões de Vestibular Comentadas sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 799 questões

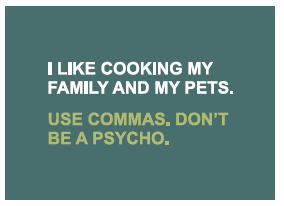

Para se evitar o qualificativo de “psicopata”, seria aconselhável seguir a recomendação do meme e inserir uma vírgula logo após

O recurso expressivo que contribui de maneira decisiva para a compreensão do cartum é

No livro Sapiens: A brief history of humankind, do autor Yuval Noah Harari, há o seguinte trecho:

Like it or not, we are members of a large and particularly noisy family called the great apes. Our closest living relatives include chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. The chimpanzees are the closest. Just 6 million years ago, a single female ape had two daughters. One became the ancestor of all chimpanzees, the other is our own grandmother.

(Sapiens: A brief history of humankind, 2014.)

Em trecho anterior, o autor indica que o surgimento de organismos vivos data de 3,8 bilhões de anos atrás. Comparada a essa informação anterior, a expressão “Just 6 million years ago”, presente no trecho transcrito, justifica-se por indicar que a origem da espécie humana é ____________ , pois corresponde a __________ do período do surgimento dos organismos vivos.

Os termos que completam as lacunas da frase são, respectivamente:

The business of climate change

A UN assessment published this week on the progress made in stemming the global loss of species made depressing reading. Not one of the 20 targets adopted by 196 countries in a convention on biodiversity in 2010 has been met. And the latest biennial Living Planet Report from the WWF, an environmental group, found that animal populations worldwide shrank by an average of two-thirds between 1970 and 2016. The falls were greatest in the tropics. In Latin America and the Caribbean animal populations fell by 94%, on average, during the period. It is some comfort that around the world biodiversity and climate change have become big political issues. In Australia koala bears have almost brought down a state government.

(www.economist.com, 18.09.2020.)

The business of climate change

A UN assessment published this week on the progress made in stemming the global loss of species made depressing reading. Not one of the 20 targets adopted by 196 countries in a convention on biodiversity in 2010 has been met. And the latest biennial Living Planet Report from the WWF, an environmental group, found that animal populations worldwide shrank by an average of two-thirds between 1970 and 2016. The falls were greatest in the tropics. In Latin America and the Caribbean animal populations fell by 94%, on average, during the period. It is some comfort that around the world biodiversity and climate change have become big political issues. In Australia koala bears have almost brought down a state government.

(www.economist.com, 18.09.2020.)

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

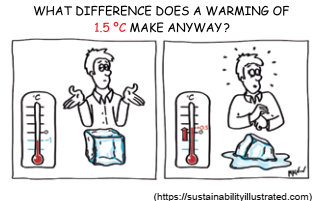

De acordo com o cartum,

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

O cartum ilustra que o aumento de temperatura, também

citado no texto,

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

Examine o cartum de Sofia Warren, publicado em sua conta no Instagram em 09.03.2020.

Contribuem para o efeito de humor do cartum os seguintes

recursos expressivos:

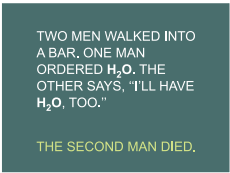

Examine a anedota publicada pela comunidade “The Language Nerds” em sua conta no Facebook em 22.01.2020.

A anedota sugere que

Examine a tira de Alex Culang e Raynato Castro.

Para que a história tivesse um desfecho favorável à garota,

seria necessário

(nytimes.com)

Shimmering white and gracefully statuesque, the Mount Washington Hotel is a granite fortress, a manmade anomaly among the raw wilderness of the surrounding White Mountains in remote northern New Hampshire, U.S. Even to this day, the hotel is geographically secured by 800,000 acres of the White Mountain National Forest around it. This was the main reason why the Hotel was chosen for a World War Two meeting – a meeting that shaped present-day global economic policies.

(Linda Laban. www.bbc.com, 26.08.2020. Adapted.)

The term “this”, which introduces the last sentence in the text, refers to the fact that the Mount Washington Hotel

(www.economist.com, 13.08.2020. Adapted.)

The descriptions in the paragraph

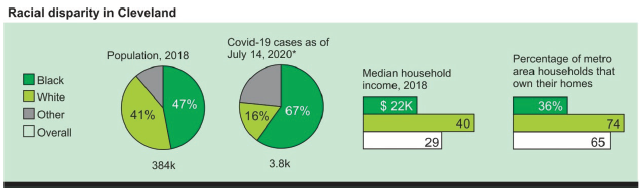

Bypassed by the rescue

In a pandemic that’s wreaked widespread economic havoc, Cleveland has been among the hardesthit cities in the U.S. And at a time when the U.S. is engaged in another conversation about its foundational racial inequalities, not much of Washington’ $2 trillion has reached Cleveland’s predominantly Black neighborhoods.

(Bloomberg Businessweek, 20.07.2020. Adapted.)

By comparing the text and the graphs it is possible to state that