Questões de Vestibular

Comentadas sobre sinônimos | synonyms em inglês

Foram encontradas 27 questões

Text 1

What is Distance Learning and Why Is It So Important?

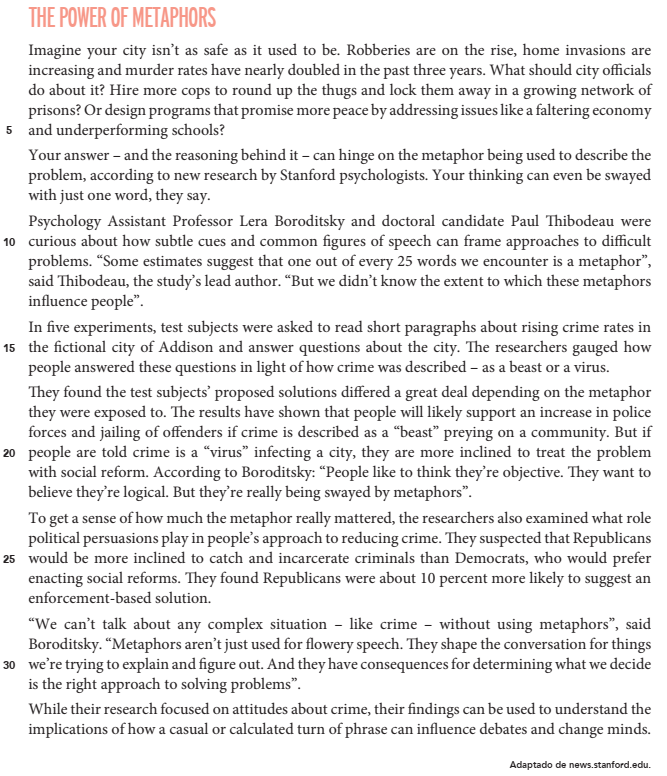

Metaphors aren’t just used for flowery speech. They shape the conversation for things we’re trying to explain and figure out. (ℓ. 29-30)

In order to clarify the meaning relation between the two sentences above, the following word can be inserted in the underlined one:

Why so few nurses are men

Ask health professionals in any country what the biggest problem in their health-care system is and one of the most common answers is the shortage of nurses. In ageing rich countries, demand for nursing care is becoming increasingly insatiable. Britain’s National Health Service, for example, has 40,000-odd nurse vacancies. Poor countries struggle with the emigration of nurses for greener pastures. One obvious solution seems neglected: recruit more men. Typically, just 5-10% of nurses registered in a given country are men. Why so few?

Views of nursing as a “woman’s job” have deep roots. Florence Nightingale, who established the principles of modern nursing in the 1860s, insisted that men’s “hard and horny” hands were “not fitted to touch, bathe and dress wounded limbs”. In Britain the Royal College of Nursing, the profession’s union, did not even admit men as members until 1960. Some nursing schools in America started admitting men only in 1982, after a Supreme Court ruling forced them to. Senior nurse titles such as “sister” (a ward manager) and “matron” (which in some countries is used for men as well) do not help matters. Unsurprisingly, some older people do not even know that men can be nurses too. Male nurses often encounter patients who assume they are doctors.

Another problem is that beliefs about what a nursing job entails are often outdated – in ways that may be particularly off-putting for men. In films, nurses are commonly portrayed as the helpers of heroic male doctors. In fact, nurses do most of their work independently and are the first responders to patients in crisis. To dispel myths, nurse-recruitment campaigns display nursing as a professional job with career progression, specialisms like anaesthetics, cardiology or emergency care, and use for skills related to technology, innovation and leadership. However, attracting men without playing to gender stereotypes can be tricky. “Are you man enough to be a nurse?”, the slogan of an American campaign, was involved in controversy.

Nursing is not a career many boys aspire to, or are encouraged to consider. Only two-fifths of British parents say they would be proud if their son became a nurse. Because of all this, men who go into nursing are usually already closely familiar with the job. Some are following in the career footsteps of their mothers. Others decide that the job would suit them after they see a male nurse care for a relative or they themselves get care from a male nurse when hospitalised. Although many gender stereotypes about jobs and caring have crumbled, nursing has, so far, remained unaffected.

(www.economist.com, 22.08.2018. Adaptado.)

Why so few nurses are men

Ask health professionals in any country what the biggest problem in their health-care system is and one of the most common answers is the shortage of nurses. In ageing rich countries, demand for nursing care is becoming increasingly insatiable. Britain’s National Health Service, for example, has 40,000-odd nurse vacancies. Poor countries struggle with the emigration of nurses for greener pastures. One obvious solution seems neglected: recruit more men. Typically, just 5-10% of nurses registered in a given country are men. Why so few?

Views of nursing as a “woman’s job” have deep roots. Florence Nightingale, who established the principles of modern nursing in the 1860s, insisted that men’s “hard and horny” hands were “not fitted to touch, bathe and dress wounded limbs”. In Britain the Royal College of Nursing, the profession’s union, did not even admit men as members until 1960. Some nursing schools in America started admitting men only in 1982, after a Supreme Court ruling forced them to. Senior nurse titles such as “sister” (a ward manager) and “matron” (which in some countries is used for men as well) do not help matters. Unsurprisingly, some older people do not even know that men can be nurses too. Male nurses often encounter patients who assume they are doctors.

Another problem is that beliefs about what a nursing job entails are often outdated – in ways that may be particularly off-putting for men. In films, nurses are commonly portrayed as the helpers of heroic male doctors. In fact, nurses do most of their work independently and are the first responders to patients in crisis. To dispel myths, nurse-recruitment campaigns display nursing as a professional job with career progression, specialisms like anaesthetics, cardiology or emergency care, and use for skills related to technology, innovation and leadership. However, attracting men without playing to gender stereotypes can be tricky. “Are you man enough to be a nurse?”, the slogan of an American campaign, was involved in controversy.

Nursing is not a career many boys aspire to, or are encouraged to consider. Only two-fifths of British parents say they would be proud if their son became a nurse. Because of all this, men who go into nursing are usually already closely familiar with the job. Some are following in the career footsteps of their mothers. Others decide that the job would suit them after they see a male nurse care for a relative or they themselves get care from a male nurse when hospitalised. Although many gender stereotypes about jobs and caring have crumbled, nursing has, so far, remained unaffected.

(www.economist.com, 22.08.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

The time has gone, the song is over (ℓ. 22)

The expression has gone refers to an action that can be described as:

The global health community has largely come to realize that public health preparedness is crucial (ℓ. 23-24)

Another word from the text that may replace the underlined one above without significant change in meaning is:

In today’s political climate, it sometimes feels like we can’t even agree on basic facts. We bombard each other with statistics and figures, hoping that more data will make a difference. A progressive person might show you the same climate change graphs over and over while a conservative person might point to the trillions of dollars of growing national debt. We’re left wondering, “Why can’t they just see? It’s so obvious!”

Certain myths are so pervasive that no matter how many experts disprove them, they only seem to grow in popularity. There’s no shortage of serious studies showing no link between autism and vaccines, for example, but these are no match for an emotional appeal to parents worried for their young children.

Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, studies how our minds work and how we process new information. In her upcoming book, The Influential Mind, she explores why we ignore facts and how we can get people to actually listen to the truth. Tali shows that we’re open to new information – but only if it confirms our existing beliefs. We find ways to ignore facts that challenge our ideals. And as neuroscientist Bahador Bahrami and colleagues have found, we weigh all opinions as equally valid, regardless of expertise.

So, having the data on your side is not always enough. For better or for worse, Sharot says, emotions may be the key to changing minds.

(Shankar Vedantam. www.npr.org. Adaptado.)

Drinking coffee could help you live longer Coffee not only helps you feel full of beans, it might add years to your life as well, two major studies have shown. Scientists in Europe and the US have uncovered the clearest evidence yet that drinking coffee reduces the risk of death.

One study of more than half a million people from 10 European countries found that men who downed at least three cups of coffee a day were 18% less likely to die from any cause than non-coffee drinkers. Women drinking the same amount benefited less, but still experienced an 8% reduction in mortality over the period measured.

Similar results were reported by American scientists who conducted a separate investigation, recruiting 185855 participants from different ethnic backgrounds. Irrespective of ethnicity, people who drank two to three cups of coffee daily had an 18% reduced risk of death.

Each of the studies, both published in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, showed no advantage from drinking either caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee. Experts believe the antioxidant plant compounds in coffee rather than caffeine are responsible for the life-extending effect. Previous research has suggested that drinking coffee can reduce the risk of heart disease, diabetes, liver disease, and some cancers.

Dr Marc Gunter, from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, who led the European study with colleagues from Imperial College London, said: “We found that higher coffee consumption was associated with a lower risk of death from any cause and specifically for circulatory diseases and digestive diseases. Importantly, these results were similar across all of the 10 European countries, with variable coffee drinking habits and customs. Our study also offers important insights into the possible mechanisms for the beneficial health effects of coffee.”

(www.huffingtonpost.co.uk, 11.07.2017. Adaptado.)

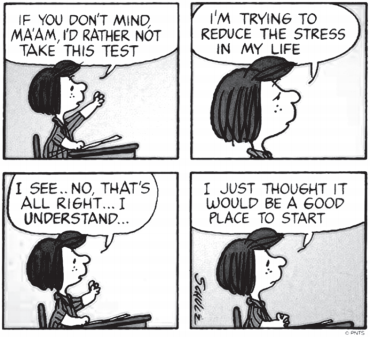

Disponível em: https://i.pinimg.com/736x/52/44/12/5244127bd1ca02b0bd30a8f8db96875a--peanuts-cartoon-peanuts-snoopy.jpg Acesso em: 30 de ago. 2017.

De acordo com o TEXTO, na frase “I’m trying to reduce the stress in my life ”, a palavra reduce só NÃO é sinônimo

de:

Examine a tira para responder à questão.

Question: Is there anything I can do to train my body to need less sleep?

Karen Weintraub

June 17, 2016

Many people think they can teach themselves to need less sleep, but they’re wrong, said Dr. Sigrid Veasey, a professor at the Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. We might feel that we’re getting by fine on less sleep, but we’re deluding ourselves, Dr. Veasey said, largely because lack of sleep skews our self-awareness. “The more you deprive yourself of sleep over long periods of time, the less accurate you are of judging your own sleep perception,” she said.

Multiple studies have shown that people don’t functionally adapt to less sleep than their bodies need. There is a range of normal sleep times, with most healthy adults naturally needing seven to nine hours of sleep per night, according to the National Sleep Foundation. Those over 65 need about seven to eight hours, on average, while teenagers need eight to 10 hours, and school-age children nine to 11 hours. People’s performance continues to be poor while they are sleep deprived, Dr. Veasey said.

Health issues like pain, sleep apnea or autoimmune disease can increase people’s need for sleep, said Andrea Meredith, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. A misalignment of the clock that governs our sleep-wake cycle can also drive up the need for sleep, Dr. Meredith said. The brain’s clock can get misaligned by being stimulated at the wrong time of day, she said, such as from caffeine in the afternoon or evening, digital screen use too close to bedtime, or even exercise at a time of day when the body wants to be winding down.

(http://well.blogs.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)