Questões de Vestibular CÁSPER LÍBERO 2014 para Vestibular

Foram encontradas 50 questões

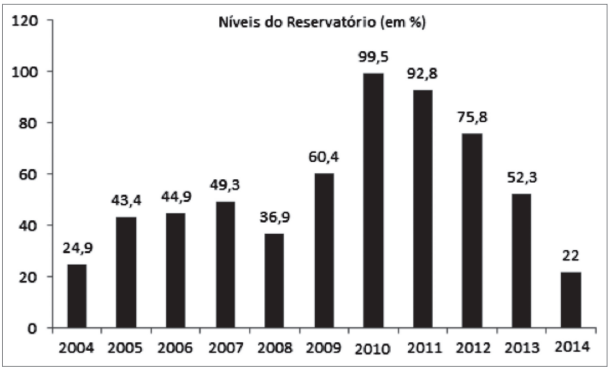

Fonte: Sabesp e Inmet

Com base nas informações acima podemos afirmar que:

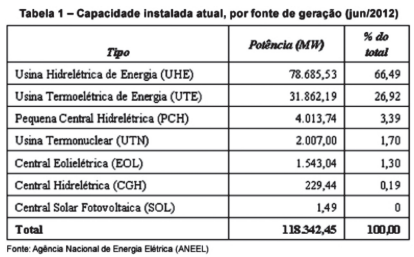

potência da Usina Hidrelétrica de Energia (UHE)? (Dados: 1 kW = 1.000 W; 1 MW = 1.000.000 W)

Suponha que a Usina Termoelétrica de Energia (UTE) utilize apenas carvão como combustível, e que cada kg de carvão produza 10kW de potência: quantas toneladas de carvão a mais, aproximadamente, as usinas UTE precisariam utilizar para alcançar a

Compare Vietnã, Golfo e Afeganistão Guerra do Vietnã 1955-75

Inicialmente, a participação americana se restringe à ajuda econômica e militar (conselheiros e material bélico). Em agosto de 1964, após ataques norte-vietnamitas ao destróier americano Maddox, o congresso americano autoriza o presidente a lançar os EUA em guerra e essa é a data considerada oficial da participação dos EUA no conflito. Total de americanos participantes: 8.722.000 Número de americanos mortos: 58.193 Número de vietnamitas mortos: mais de 1 milhão Em 15 anos de guerra, foram jogadas sobre o Vietnã mais toneladas de bombas do que todas as lançadas durante a 2ª Guerra Mundial. Houve também experiências com armas químicas e bacteriológicas. Os Estados Unidos gastaram mais de 150 bilhões de dólares, destruíram cerca de 70% de todos os povoados do Norte e inutilizaram mais de 10 milhões de hectares de terra.

Guerra do Golfo 1991

Em agosto de 1990, o Iraque invadiu o Kwait, fez milhares de reféns estrangeiros e anunciou a anexação do país. Em 17 de janeiro de 1991, as tropas aliadas, uma aliança de 32 países, lideradas pelos Estados Unidos, iniciam um maciço ataque contra o Iraque, visando à desocupação do Kwait. O cessar-fogo foi decretado pelo presidente Bush em 27 de fevereiro do mesmo ano. Total de militares americanos participantes: 467.939 (estimado) Número de aliados mortos: 299 Número de iraquianos mortos: entre 150 e 200 mil Pela primeira vez foram usadas armas de alta precisão, as chamadas bombas de “precisão cirúrgica” (que errariam o alvo por no máximo três metros), entre eles os mísseis Tomahawk, que podem ser lançados de submarinos, cruzadores e destróieres. Chegam a ter alcance de cerca de 1.104 km, velocidade de 880 km/h e custam US$ 1,2 milhão. Também foram usados os caças “invisíveis” F-117. Os países aliados gastaram US$ 61 bilhões no conflito. “

Comparando os números das duas guerras, podemos perceber que o poder de destruição das armas que vão surgindo com o passar do tempo

Os adolescentes são as maiores vítimas, e não os principais autores da violência “ Até junho de 2011, cerca de 90 mil adolescentes cometeram atos infracionais. Destes, cerca de 30 mil cumprem medidas socioeducativas. O número, embora considerável, corresponde a 0,5% da população jovem do Brasil, que conta com 21 milhões de meninos e meninas entre 12 e 18 anos. Os homicídios de adolescentes brasileiros cresceram vertiginosamente nas últimas décadas: 346% entre 1980 e 2010. De 1981 a 2010, mais de 176 mil foram mortos e só em 2010 o número foi de 8.686 adolescentes assassinados.” Fonte: Congresso em foco

Estes números alarmantes nos mostram que no ano de 2010 morreram aproximadamente