Questões de Vestibular CEDERJ 2018 para Vestibular - Primeiro Semestre

Foram encontradas 60 questões

Aproveitando uma “promoção”, Maria conseguiu

comprar uma mercadoria pela fração  do seu preço

original. O percentual de desconto foi de

do seu preço

original. O percentual de desconto foi de

Se x e y são números reais, tais que 0 < x < π/2, 0 < y < π/2, sen(x) = 4/5 e cos(y) = 1/3, então o quociente  é igual a

é igual a

a) ¼ dos meninos tem olhos verdes;

b) escolhido, ao acaso, um estudante da turma, a probabilidade de ele ser menino e de ter olhos verdes é 1/10.

O número de meninos dessa turma é:

Sejam p e q números inteiros.

A sentença verdadeira é:

O dióxido de titânio, além de ser empregado como aditivo alimentar, é comumente usado para pigmentação branca em tintas, papel e plásticos. É também um ingrediente ativo, em protetores solares baseados em minerais, usado para a pigmentação com o objetivo de bloquear a luz ultravioleta. Além disso, o óxido também é usado em alguns chocolates para dar uma textura suave; em donuts, para fornecer cor; e em leites desnatados, para dar uma aparência mais brilhante, mais opaca, o que torna o produto mais saboroso.

Uma das reações utilizadas para a sua produção é a cloração de um mineral de titânio (ilmenita) cuja equação é a seguinte:

x FeTiO3 (s) + y Cl2 (g) + z C(s) → a FeCl2 (s) + bTiO2(s) + c CO2 (g)

Os números para os coeficientes x, y, z, a, b, c, que tornam

essa equação balanceada, são, respectivamente:

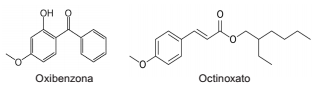

Muitos dos protetores solares disponíveis no mercado contêm duas substâncias químicas: a oxibenzona e o octinoxato. Estudos científicos realizados em laboratório associam essas substâncias a problemas de reprodução e de branqueamento de corais, o que os deixa enfraquecidos e, com o tempo, os leva à morte. Em 2016, uma equipe de cientistas americanos relatou que essas substâncias poderiam interromper o crescimento dos corais. Esses filtros químicos são liberados pela pele humana à medida que as pessoas mergulham, nadam ou surfam no mar.

Considere as fórmulas estruturais planas:

Em relação a essas moléculas, é correto afirmar que

A desomorfina, assim como a morfina e a heroína, é um derivado do ópio. Usada para fins medicinais na terapia da dor crônica e aguda de alta intensidade, a desomorfina produz fortes ações de insensibilidade à dor. A ingestão de doses elevadas da substância causa euforia, estados hipnóticos e dependência. A desomorfina é de 8 a 10 vezes mais potente que a morfina, tratando-se de um opiáceo sintético com estrutura quase idêntica à da heroína, mas muito mais barata.

Supondo que, a 25 °C, a desomorfina tenha um pKa de 9,69, a morfina tenha um pKa de 8,21 e a heroína tenha um pKa de 7,60, tem-se que a

Dentre os diversos agentes tóxicos, o arsênio é historicamente famoso por se tratar de uma substância muito utilizada na Idade Média para assassinatos com interesses políticos. Podemos até dizer que a morte por arsênio foi a precursora da química forense. Na época, havia uma epidemia desses casos, cuja prevenção era muito difícil, uma vez que óxido de arsênio, As2O3, é um sólido branco, solúvel, sem cheiro e gosto, sendo dificilmente detectado por análises químicas convencionais, o que lhe deu o status de óxido do crime perfeito. Além disso, o óxido de arsênio (III) é um composto muito utilizado na fabricação de vidros e inseticidas. Ele é convertido em ácido arsenioso (H3AsO3 ) em contato com água. Um método para se determinar o teor de arsênio é por meio de oxidação com permanganato de potássio e ácido sulfúrico, conforme equação não balanceada a seguir:

H3AsO3 + KMnO4 + H2SO4 → H3AsO4 + K2SO4 + MnSO4 + H2O

Sabendo que para 2,000 g de amostra foram gastos

10,00 mL de uma solução de KMnO4 0,05 M, em que ocorre a reação acima completa, em meio de ácido sulfúrico, o

percentual de arsênio na amostra é:

As pilhas são dispositivos que receberam esse nome porque a primeira pilha inventada por Alessandro Volta, no ano de 1800, e era formada por discos de zinco e cobre separados por um algodão embebido em salmoura. Tal conjunto era colocado de forma intercalada, um em cima do outro, empilhando os discos e formando uma grande coluna. Como era uma pilha de discos, começou a ser chamada por esse nome.

Afirma-se que, numa pilha eletroquímica, sempre ocorre

I oxidação no ânodo.

II movimentação de elétrons no interior da solução eletrolítica.

III passagem de elétrons, no circuito externo, do cátodo para o ânodo.

IV uma reação de oxirredução.

São verdadeiras apenas as afirmações estabelecidas em:

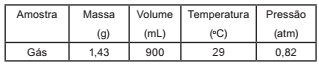

Um laboratório de controle ambiental recebeu para análise uma amostra de gás sem identificação. Após algumas medidas, foram obtidos os seguintes dados:

Com base nos valores obtidos, entre os gases indicados

nas opções, conclui-se que a amostra era de:

Fake news could ruin social media, but there’s still hope

by: Guðrun í Jákupsstovu

Camille Francois, director of research and analysis at Graphika, told the audience of her talk at TNW Conference:

“Disinformation campaigns, or fake news is a concept we’ve known about for years, but few people realize how varied the concept can be and how many forms it comes in. When the first instances of fake news started to surface, they were connected with bots. These flooded conversations with alternative stories in order to create noise and, in turn, silence what was actually being said”.

According to Francois, today’s disinformation campaigns are far more varied than just bots – and much harder to detect. For example, targeted harassment campaigns are carried out against journalists and human-rights activists who are critical of governments or big organizations.

“We see this kind of campaigns happening at large scale in countries like the Philippines, Turkey, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The point of these campaigns is to flood the narrative these people try to create with so much noise that their original message gets silenced, their reputation gets damaged, and their credibility undermined. I call this patriotic trolling.”

There are also examples of disinformation campaigns mobilizing people. This was evident during the US elections in 2016 when many fake events suddenly started popping up on Facebook. One Russian Facebook page “organized” an anti-Islam event, while another “organized” a pro-Islam demonstration. The two fake events gathered activists to the same street in Texas, leading to a stand-off.

Francois explains how amazed she is that, in spite of social media being the main medium for these different disinformation campaigns, actual people also still use it to protest properly.

If we look at countries, like Turkey – where there’s a huge amount of censorship and smear campaigns directed at human right defenders and journalists – citizens around the world and in those places still use social media to denounce corruption, to organize human rights movements and this proves that we still haven’t lost the battle of who owns social media.

This is an ongoing battle, and it lets us recognize the actors who are trying to remove the option for people to use social media for good. But everyday you still have people all over the world turning to social media to support their democratic activities. This gives me hope and a desire to protect people’s ability to use social media for good, for denouncing corruption and protecting human rights.

Adapted from:<https://thenextweb.com/socialmedia/2018/05/25/>

Fake news could ruin social media, but there’s still hope

by: Guðrun í Jákupsstovu

Camille Francois, director of research and analysis at Graphika, told the audience of her talk at TNW Conference:

“Disinformation campaigns, or fake news is a concept we’ve known about for years, but few people realize how varied the concept can be and how many forms it comes in. When the first instances of fake news started to surface, they were connected with bots. These flooded conversations with alternative stories in order to create noise and, in turn, silence what was actually being said”.

According to Francois, today’s disinformation campaigns are far more varied than just bots – and much harder to detect. For example, targeted harassment campaigns are carried out against journalists and human-rights activists who are critical of governments or big organizations.

“We see this kind of campaigns happening at large scale in countries like the Philippines, Turkey, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The point of these campaigns is to flood the narrative these people try to create with so much noise that their original message gets silenced, their reputation gets damaged, and their credibility undermined. I call this patriotic trolling.”

There are also examples of disinformation campaigns mobilizing people. This was evident during the US elections in 2016 when many fake events suddenly started popping up on Facebook. One Russian Facebook page “organized” an anti-Islam event, while another “organized” a pro-Islam demonstration. The two fake events gathered activists to the same street in Texas, leading to a stand-off.

Francois explains how amazed she is that, in spite of social media being the main medium for these different disinformation campaigns, actual people also still use it to protest properly.

If we look at countries, like Turkey – where there’s a huge amount of censorship and smear campaigns directed at human right defenders and journalists – citizens around the world and in those places still use social media to denounce corruption, to organize human rights movements and this proves that we still haven’t lost the battle of who owns social media.

This is an ongoing battle, and it lets us recognize the actors who are trying to remove the option for people to use social media for good. But everyday you still have people all over the world turning to social media to support their democratic activities. This gives me hope and a desire to protect people’s ability to use social media for good, for denouncing corruption and protecting human rights.

Adapted from:<https://thenextweb.com/socialmedia/2018/05/25/>

Fake news could ruin social media, but there’s still hope

by: Guðrun í Jákupsstovu

Camille Francois, director of research and analysis at Graphika, told the audience of her talk at TNW Conference:

“Disinformation campaigns, or fake news is a concept we’ve known about for years, but few people realize how varied the concept can be and how many forms it comes in. When the first instances of fake news started to surface, they were connected with bots. These flooded conversations with alternative stories in order to create noise and, in turn, silence what was actually being said”.

According to Francois, today’s disinformation campaigns are far more varied than just bots – and much harder to detect. For example, targeted harassment campaigns are carried out against journalists and human-rights activists who are critical of governments or big organizations.

“We see this kind of campaigns happening at large scale in countries like the Philippines, Turkey, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The point of these campaigns is to flood the narrative these people try to create with so much noise that their original message gets silenced, their reputation gets damaged, and their credibility undermined. I call this patriotic trolling.”

There are also examples of disinformation campaigns mobilizing people. This was evident during the US elections in 2016 when many fake events suddenly started popping up on Facebook. One Russian Facebook page “organized” an anti-Islam event, while another “organized” a pro-Islam demonstration. The two fake events gathered activists to the same street in Texas, leading to a stand-off.

Francois explains how amazed she is that, in spite of social media being the main medium for these different disinformation campaigns, actual people also still use it to protest properly.

If we look at countries, like Turkey – where there’s a huge amount of censorship and smear campaigns directed at human right defenders and journalists – citizens around the world and in those places still use social media to denounce corruption, to organize human rights movements and this proves that we still haven’t lost the battle of who owns social media.

This is an ongoing battle, and it lets us recognize the actors who are trying to remove the option for people to use social media for good. But everyday you still have people all over the world turning to social media to support their democratic activities. This gives me hope and a desire to protect people’s ability to use social media for good, for denouncing corruption and protecting human rights.

Adapted from:<https://thenextweb.com/socialmedia/2018/05/25/>

Fake news could ruin social media, but there’s still hope

by: Guðrun í Jákupsstovu

Camille Francois, director of research and analysis at Graphika, told the audience of her talk at TNW Conference:

“Disinformation campaigns, or fake news is a concept we’ve known about for years, but few people realize how varied the concept can be and how many forms it comes in. When the first instances of fake news started to surface, they were connected with bots. These flooded conversations with alternative stories in order to create noise and, in turn, silence what was actually being said”.

According to Francois, today’s disinformation campaigns are far more varied than just bots – and much harder to detect. For example, targeted harassment campaigns are carried out against journalists and human-rights activists who are critical of governments or big organizations.

“We see this kind of campaigns happening at large scale in countries like the Philippines, Turkey, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The point of these campaigns is to flood the narrative these people try to create with so much noise that their original message gets silenced, their reputation gets damaged, and their credibility undermined. I call this patriotic trolling.”

There are also examples of disinformation campaigns mobilizing people. This was evident during the US elections in 2016 when many fake events suddenly started popping up on Facebook. One Russian Facebook page “organized” an anti-Islam event, while another “organized” a pro-Islam demonstration. The two fake events gathered activists to the same street in Texas, leading to a stand-off.

Francois explains how amazed she is that, in spite of social media being the main medium for these different disinformation campaigns, actual people also still use it to protest properly.

If we look at countries, like Turkey – where there’s a huge amount of censorship and smear campaigns directed at human right defenders and journalists – citizens around the world and in those places still use social media to denounce corruption, to organize human rights movements and this proves that we still haven’t lost the battle of who owns social media.

This is an ongoing battle, and it lets us recognize the actors who are trying to remove the option for people to use social media for good. But everyday you still have people all over the world turning to social media to support their democratic activities. This gives me hope and a desire to protect people’s ability to use social media for good, for denouncing corruption and protecting human rights.

Adapted from:<https://thenextweb.com/socialmedia/2018/05/25/>