Questões de Vestibular UENP 2018 para Vestibular - 1º Dia

Foram encontradas 10 questões

Em relação aos recursos linguístico-semânticos do texto, relacione as colunas de modo a identificar a função dos termos em destaque.

(I) Until this changes, Gaviorno and her colleagues will have their work cut out.

(II) From the female lawyer who asks for something from the judge and gets it because she is pretty, to the woman who is murdered by her husband. . .

(III) Everyone arrested for violence against women must attend an introductory lecture.

(IV) “You can’t just wait with your arms folded while the justice system takes its time to do something,”

(V) Group sessions are run like an AA group.

(A) Demonstra obrigatoriedade de uma ação.

(B) Aponta “limite” de algo.

(C) Demonstra que duas ações acontecem ao mesmo tempo.

(D) Aponta “origem e limite” de algo.

(E) Compara duas ideias.

Assinale a alternativa que contém a associação correta.

Com relação às informações trazidas pelo texto, atribua V (verdadeiro) ou F (falso) às afirmativas a seguir.

( ) Um quinto das mulheres relatam ter sofrido algum tipo de violência no ano de 2017.

( ) A definição de violência restringe-se a tentativas de assassinato.

( ) Outras ações são desnecessárias já que o projeto está sendo bem sucedido.

( ) A violência no Estado do Espírito Santo vem aumentando desde 2005.

( ) O programa tem um papel pequeno no enfrentamento da violência contra a mulher

* ’Hitting women isn’t normal’: tackling male violence in Brazil. * A rehabilitation programme for violent men in Espírito Santo is cutting reoffending rates. * The programme, run by police professionals, has been successful. * Everyone arrested for violence against women must attend an introductory lecture. * “I start off explaining that hitting a woman isn’t normal and is a crime.”

Assinale a alternativa que apresenta, corretamente, de cima para baixo, o significado dos verbos em negrito.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

De acordo com o infográfico, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. Os pobres e os marginalizados são maioria quando se trata de falta de habilidade de leitura e escrita.

II. Mais da metade dos analfabetos em idade adulta são mulheres.

III. 30% das crianças não completam o ensino primário em países desenvolvidos.

IV. 250 milhões de crianças frequentam a escola primária.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

Em relação ao que se pode inferir do infográfico, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. Leitura e aritmética são consideradas habilidades necessárias para a vida e para o mercado de trabalho.

II. A questão da falta de habilidades atinge crianças, jovens e adultos.

III. Há um elevado número de crianças que não terminam o ensino primário.

IV. A quantidade de educadores é dado relevante para o enfrentamento dos problemas na Educação.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

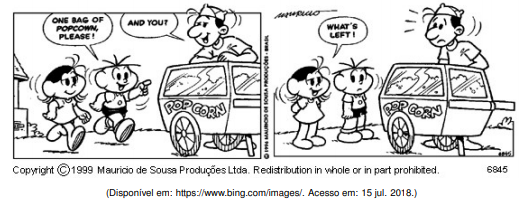

Leia a tirinha a seguir.

Na tirinha, o humor é evidenciado por meio