Questões de Vestibular UNESP 2016 para Vestibular - Segundo Semestre

Foram encontradas 90 questões

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

129. Se a esposa de alguém for surpreendida em flagrante com outro homem, ambos devem ser amarrados e jogados dentro d’água, mas o marido pode perdoar a sua esposa, assim como o rei perdoa a seus escravos. [...]

133. Se um homem for tomado como prisioneiro de guerra, e houver sustento em sua casa, mas mesmo assim sua esposa deixar a casa por outra, esta mulher deverá ser judicialmente condenada e atirada na água. [...]

135. Se um homem for feito prisioneiro de guerra e não houver quem sustente sua esposa, ela deverá ir para outra casa e criar seus filhos. Se mais tarde o marido retornar e voltar à casa, então a esposa deverá retornar ao marido, assim como as crianças devem seguir seu pai. [...]

138. Se um homem quiser se separar de sua esposa que lhe deu filhos, ele deve dar a ela a quantia do preço que pagou por ela e o dote que ela trouxe da casa de seu pai, e deixá-la partir.

(www.direitoshumanos.usp.br)

Esses quatro preceitos, selecionados do Código de Hamurabi (cerca de 1780 a.C.), indicam uma sociedade caracterizada

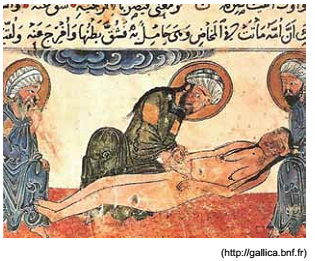

Examine a iluminura extraída do manuscrito Al-Maqamat, de Abu Muhammed al-Kasim al-Hariri, 1237.

A imagem pode ser associada à tradição dos conhecimentos

desenvolvidos no mundo árabe-islâmico durante a Idade Média e revela

Os mosteiros eram em primeiro lugar casas, cada uma abrigando sua “família”, e as mais perfeitas, com efeito, as mais bem ordenadas: de um lado, desde o século IX, os mais abundantes recursos convergiam para a instituição monástica, levando-a aos postos avançados do progresso cultural; do outro, tudo ali se encontrava organizado em função de um projeto de perfeição, nítido, bem estabelecido, rigorosamente medido.

(Georges Duby. “A vida privada nas casas aristocráticas da França feudal”. História da vida privada, vol. 2, 1992. Adaptado.)

A caracterização do mosteiro medieval como uma “casa”, um “posto avançado do progresso cultural” e um “projeto de perfeição” pode ser explicada pela disposição monástica de

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Prova da barbárie e, para alguns, da natureza não humana do ameríndio, a antropofagia condenava as tribos que a praticavam a sofrer pelas armas portuguesas a “guerra justa”.

Nesse contexto, um dos autores renascentistas que escreveram sobre o Brasil, o calvinista francês Jean de Léry, morador do atual Rio de Janeiro na segunda metade da década de 1550 e quase vítima dos massacres do Dia de São Bartolomeu (24.08.1572), ponto alto das guerras de religião na França, compara a violência dos tupinambás com a dos católicos franceses que naquele dia fatídico trucidaram e, em alguns casos, devoraram seus compatriotas protestantes:

“E o que vimos na França (durante o São Bartolomeu)? Sou francês e pesa-me dizê-lo. O fígado e o coração e outras partes do corpo de alguns indivíduos não foram comidos por furiosos assassinos de que se horrorizam os infernos? Não é preciso ir à América, nem mesmo sair de nosso país, para ver coisas tão monstruosas”.

(Luís Felipe Alencastro. “Canibalismo deu pretexto para escravizar”.

Folha de S.Paulo, 12.10.1991. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Prova da barbárie e, para alguns, da natureza não humana do ameríndio, a antropofagia condenava as tribos que a praticavam a sofrer pelas armas portuguesas a “guerra justa”.

Nesse contexto, um dos autores renascentistas que escreveram sobre o Brasil, o calvinista francês Jean de Léry, morador do atual Rio de Janeiro na segunda metade da década de 1550 e quase vítima dos massacres do Dia de São Bartolomeu (24.08.1572), ponto alto das guerras de religião na França, compara a violência dos tupinambás com a dos católicos franceses que naquele dia fatídico trucidaram e, em alguns casos, devoraram seus compatriotas protestantes:

“E o que vimos na França (durante o São Bartolomeu)? Sou francês e pesa-me dizê-lo. O fígado e o coração e outras partes do corpo de alguns indivíduos não foram comidos por furiosos assassinos de que se horrorizam os infernos? Não é preciso ir à América, nem mesmo sair de nosso país, para ver coisas tão monstruosas”.

(Luís Felipe Alencastro. “Canibalismo deu pretexto para escravizar”.

Folha de S.Paulo, 12.10.1991. Adaptado.)

Todos os homens são criados iguais, dotados pelo Criador de certos direitos inalienáveis, entre os quais figuram a vida, a liberdade e a busca da felicidade. Para assegurar esses direitos, entre os homens se instituem governos, que derivam seus justos poderes do consentimento dos governados. Sempre que uma forma de governo se dispõe a destruir essas finalidades, cabe ao povo o direito de alterá-la ou aboli-la, e instituir um novo governo, assentando seu fundamento sobre tais princípios e organizando seus poderes de tal forma que a ele pareça ter maior probabilidade de alcançar-lhe a segurança e a felicidade.

(Declaração de Independência dos Estados Unidos (1776). In: Harold Syrett (org.). Documentos históricos dos Estados Unidos, 1988.)

O documento expõe o vínculo da luta pela independência das treze colônias com os princípios

A condição essencial da existência e da supremacia da classe burguesa é a acumulação da riqueza nas mãos dos particulares, a formação e o crescimento do capital; a condição de existência do capital é o trabalho assalariado. [...] O desenvolvimento da grande indústria socava o terreno em que a burguesia assentou o seu regime de produção e de apropriação dos produtos. A burguesia produz, sobretudo, seus próprios coveiros. Sua queda e a vitória do proletariado são igualmente inevitáveis.

(Karl Marx e Friedrich Engels. “Manifesto Comunista”. Obras escolhidas, vol. 1, s/d.)

Entre as características do pensamento marxista, é correto citar

Os colonos que emigram, recebendo dinheiro adiantado, tornam-se, pois, desde o começo, uma simples propriedade de Vergueiro & Cia. E em virtude do espírito de ganância, para não dizer mais, que anima numerosos senhores de escravos, e também da ausência de direitos em que costumam viver esses colonos na província de São Paulo, só lhes resta conformarem-se com a ideia de que são tratados como simples mercadorias ou como escravos.

(Thomas Davatz. Memórias de um colono no Brasil (1850), 1941.)

O texto aponta problemas enfrentados por imigrantes europeus que vieram ao Brasil para