Questões de Vestibular UNESP 2017 para Vestibular - Segundo Semestre

Foram encontradas 90 questões

It is essential to promote social inclusion by providing spaces for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to use and enjoy. Quality public spaces such as libraries and parks can supplement housing as study and recreational spaces for the urban poor.

There is a need to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of public spaces within cities. Through the provision of quality public spaces in cities can reduce the economic and social segregation that is prevalent in many developed and developing cities. By ensuring the distribution, coverage and quality of public spaces, it is possible to directly influence the dynamics of urban density, to combine uses and to promote the social mixture of cities’ inhabitants.

Rights and duties of all the public space stakeholders should be clearly defined. Public spaces are public assets as a public space is by definition a place where all citizens are legitimate to be and discrimination should be tackled there. Public space has the capacity to gather people and break down social barriers. Protecting the inclusiveness of public space is a key prerequisite for the right to the city and an important asset to foster tolerance, conviviality and dialogue.

Public spaces in slums are only used to enable people to move. There is a lack of public space both in quantity and quality, leading to high residential density, high crime rates, lack of public facilities such as toilets or water, difficulties to practice outdoor sports and other recreational activities among others.

(www.learning.uclg.org)

It is essential to promote social inclusion by providing spaces for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to use and enjoy. Quality public spaces such as libraries and parks can supplement housing as study and recreational spaces for the urban poor.

There is a need to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of public spaces within cities. Through the provision of quality public spaces in cities can reduce the economic and social segregation that is prevalent in many developed and developing cities. By ensuring the distribution, coverage and quality of public spaces, it is possible to directly influence the dynamics of urban density, to combine uses and to promote the social mixture of cities’ inhabitants.

Rights and duties of all the public space stakeholders should be clearly defined. Public spaces are public assets as a public space is by definition a place where all citizens are legitimate to be and discrimination should be tackled there. Public space has the capacity to gather people and break down social barriers. Protecting the inclusiveness of public space is a key prerequisite for the right to the city and an important asset to foster tolerance, conviviality and dialogue.

Public spaces in slums are only used to enable people to move. There is a lack of public space both in quantity and quality, leading to high residential density, high crime rates, lack of public facilities such as toilets or water, difficulties to practice outdoor sports and other recreational activities among others.

(www.learning.uclg.org)

It is essential to promote social inclusion by providing spaces for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to use and enjoy. Quality public spaces such as libraries and parks can supplement housing as study and recreational spaces for the urban poor.

There is a need to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of public spaces within cities. Through the provision of quality public spaces in cities can reduce the economic and social segregation that is prevalent in many developed and developing cities. By ensuring the distribution, coverage and quality of public spaces, it is possible to directly influence the dynamics of urban density, to combine uses and to promote the social mixture of cities’ inhabitants.

Rights and duties of all the public space stakeholders should be clearly defined. Public spaces are public assets as a public space is by definition a place where all citizens are legitimate to be and discrimination should be tackled there. Public space has the capacity to gather people and break down social barriers. Protecting the inclusiveness of public space is a key prerequisite for the right to the city and an important asset to foster tolerance, conviviality and dialogue.

Public spaces in slums are only used to enable people to move. There is a lack of public space both in quantity and quality, leading to high residential density, high crime rates, lack of public facilities such as toilets or water, difficulties to practice outdoor sports and other recreational activities among others.

(www.learning.uclg.org)

It is essential to promote social inclusion by providing spaces for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to use and enjoy. Quality public spaces such as libraries and parks can supplement housing as study and recreational spaces for the urban poor.

There is a need to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of public spaces within cities. Through the provision of quality public spaces in cities can reduce the economic and social segregation that is prevalent in many developed and developing cities. By ensuring the distribution, coverage and quality of public spaces, it is possible to directly influence the dynamics of urban density, to combine uses and to promote the social mixture of cities’ inhabitants.

Rights and duties of all the public space stakeholders should be clearly defined. Public spaces are public assets as a public space is by definition a place where all citizens are legitimate to be and discrimination should be tackled there. Public space has the capacity to gather people and break down social barriers. Protecting the inclusiveness of public space is a key prerequisite for the right to the city and an important asset to foster tolerance, conviviality and dialogue.

Public spaces in slums are only used to enable people to move. There is a lack of public space both in quantity and quality, leading to high residential density, high crime rates, lack of public facilities such as toilets or water, difficulties to practice outdoor sports and other recreational activities among others.

(www.learning.uclg.org)

It is essential to promote social inclusion by providing spaces for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to use and enjoy. Quality public spaces such as libraries and parks can supplement housing as study and recreational spaces for the urban poor.

There is a need to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of public spaces within cities. Through the provision of quality public spaces in cities can reduce the economic and social segregation that is prevalent in many developed and developing cities. By ensuring the distribution, coverage and quality of public spaces, it is possible to directly influence the dynamics of urban density, to combine uses and to promote the social mixture of cities’ inhabitants.

Rights and duties of all the public space stakeholders should be clearly defined. Public spaces are public assets as a public space is by definition a place where all citizens are legitimate to be and discrimination should be tackled there. Public space has the capacity to gather people and break down social barriers. Protecting the inclusiveness of public space is a key prerequisite for the right to the city and an important asset to foster tolerance, conviviality and dialogue.

Public spaces in slums are only used to enable people to move. There is a lack of public space both in quantity and quality, leading to high residential density, high crime rates, lack of public facilities such as toilets or water, difficulties to practice outdoor sports and other recreational activities among others.

(www.learning.uclg.org)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

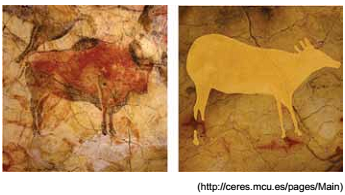

Examine duas pinturas produzidas na Caverna de Altamira, Espanha, durante o Período Paleolítico Superior.

Tais pinturas rupestres podem ser consideradas como

Em Aire-sur-la-Lys, em 15 de agosto de 1335, Jean de Picquigny, governador do condado de Artois, permite ao “maior, aos almotacés1 e à comunidade da cidade construir uma torre com um sino especial, por causa do mister da tecelagem e de outros misteres em que vários operários deslocam-se habitualmente em certas horas do dia”.

(Jacques Le Goff. Por uma outra Idade Média, 2013. Adaptado.)

1 almotacé: inspetor municipal.

O texto revela

Deveis saber, portanto, que existem duas formas de se combater: uma, pelas leis, outra, pela força. A primeira é própria do homem; a segunda, dos animais. Como, porém, muitas vezes a primeira não seja suficiente, é preciso recorrer à segunda. Ao príncipe torna-se necessário, porém, saber empregar convenientemente o animal e o homem. [...] Nas ações de todos os homens, máxime dos príncipes, onde não há tribunal para que recorrer, o que importa é o êxito bom ou mau. Procure, pois, um príncipe, vencer e conservar o Estado.

(Nicolau Maquiavel. O príncipe, 1983.)

O texto, escrito por volta de 1513, em pleno período do Renascimento italiano, orienta o governante a

Os deuses disseram entre si depois de criar o homem: “O que os homens comerão, oh deuses? Vamos já todos buscar o alimento.” Enquanto isso, as formigas vermelhas estavam colhendo e carregando os grãos de milho que traziam de dentro do Tonacatepetl (Montanha do Sustento). O deus Quetzalcoatl encontrou as formigas e lhes disse: “Digam-me, onde vocês colheram os grãos de milho?”. Muitas vezes lhes perguntou, mas as formigas não quiseram responder. Algum tempo depois, as formigas disseram a Quetzalcoatl: “Lá.” E apontaram o lugar. Quetzalcoatl se transformou em formiga negra e as acompanhou. Desse modo, Quetzalcoatl acompanhou as formigas vermelhas até o depósito, arranjou o milho e em seguida o levou a Tamoanchan (moradia dos deuses e onde o homem havia sido criado). Ali os deuses o mastigaram e o puseram na nossa boca para nos robustecer.

(Apud Eduardo Natalino dos Santos. Cidades pré-hispânicas do México e da América Central, 2004.)

O texto asteca

Nem todos os homens se renderam diante das forças irresistíveis do novo mundo fabril, e a experiência do movimento dos quebradores de máquina demonstra uma inequívoca capacidade dos trabalhadores para desencadear uma luta aberta contra o sistema de fábrica. De um lado, esse movimento de resistência visava investir contra as novas relações hierárquicas e autoritárias introduzidas no interior do processo de trabalho fabril, e nessa medida a destruição das máquinas funcionava como mecanismo de pressão contra a nova direção organizativa das empresas; de outro lado, inúmeras atividades de destruição carregaram implicitamente uma profunda hostilidade contra as novas máquinas e contra o marco organizador da produção que essa tecnologia impunha.

(Edgar de Decca. O nascimento das fábricas, 1982. Adaptado.)

De acordo com o texto, os movimentos dos quebradores de máquinas, na Inglaterra do final do século XVIII e início do XIX,

Dado que o Presidente eleito Donald Trump articulou uma visão coerente dos assuntos externos, parece que os Estados Unidos devem rejeitar a maioria das políticas do período pós-1945. Para Trump, a OTAN é um mau negócio, a corrida nuclear é algo bom, o presidente russo Vladimir Putin é um colega admirável, os grandes negócios vantajosos apenas para nós, norte-americanos, devem substituir o livre-comércio.

Com seu estilo peculiar, Trump está forçando uma pergunta que, provavelmente, deveria ter sido levantada há 25 anos: os Estados Unidos devem ser uma potência global, que mantenha a ordem mundial – inclusive com o uso de armas, o que Theodore Roosevelt chamou, como todos sabem, de Big Stick?

Curiosamente, a morte da União Soviética e o fim da Guerra Fria não provocaram imediatamente esse debate. Na década de 1990, manter um papel de liderança global para os Estados Unidos parecia barato – afinal, outras nações pagaram pela Guerra do Golfo Pérsico de 1991. Nesse conflito e nas sucessivas intervenções norte-americanas na antiga Iugoslávia, os custos e as perdas foram baixos. Então, no início dos anos 2000, os americanos foram compreensivelmente absorvidos pelas consequências do 11 de setembro e pelas guerras e ataques terroristas que se seguiram. Agora, para melhor ou para pior, o debate está nas nossas mãos.

(Eliot Cohen. “Should the U.S. still carry a ‘big stick’?”. www.latimes.com, 18.01.2017. Adaptado.)

Dado que o Presidente eleito Donald Trump articulou uma visão coerente dos assuntos externos, parece que os Estados Unidos devem rejeitar a maioria das políticas do período pós-1945. Para Trump, a OTAN é um mau negócio, a corrida nuclear é algo bom, o presidente russo Vladimir Putin é um colega admirável, os grandes negócios vantajosos apenas para nós, norte-americanos, devem substituir o livre-comércio.

Com seu estilo peculiar, Trump está forçando uma pergunta que, provavelmente, deveria ter sido levantada há 25 anos: os Estados Unidos devem ser uma potência global, que mantenha a ordem mundial – inclusive com o uso de armas, o que Theodore Roosevelt chamou, como todos sabem, de Big Stick?

Curiosamente, a morte da União Soviética e o fim da Guerra Fria não provocaram imediatamente esse debate. Na década de 1990, manter um papel de liderança global para os Estados Unidos parecia barato – afinal, outras nações pagaram pela Guerra do Golfo Pérsico de 1991. Nesse conflito e nas sucessivas intervenções norte-americanas na antiga Iugoslávia, os custos e as perdas foram baixos. Então, no início dos anos 2000, os americanos foram compreensivelmente absorvidos pelas consequências do 11 de setembro e pelas guerras e ataques terroristas que se seguiram. Agora, para melhor ou para pior, o debate está nas nossas mãos.

(Eliot Cohen. “Should the U.S. still carry a ‘big stick’?”. www.latimes.com, 18.01.2017. Adaptado.)