Questões de Vestibular UNESP 2018 para Vestibular - Primeiro Semestre

Foram encontradas 90 questões

Leia o trecho do artigo de Jason Farago, publicado pelo jornal The New York Times, para responder às questões

She led Latin American Art in a bold new direction

In 1928, Tarsila do Amaral painted Abaporu, a landmark work of Brazilian Modernism, in which a nude figure, half-human and half-animal, looks down at his massive, swollen foot, several times the size of his head. Abaporu inspired Tarsila’s husband at the time, the poet Oswald de Andrade, to write his celebrated “Cannibal Manifesto,” which flayed Brazil’s belletrist writers and called for an embrace of local influences – in fact, for a devouring of them. The European stereotype of native Brazilians as cannibals would be reformatted as a cultural virtue. More than a social and literary reform movement, cannibalism would form the basis for a new Brazilian nationalism, in which, as de Andrade wrote, “we made Christ to be born in Bahia.”

The unconventional nudes of A Negra, a painting produced in 1923, and Abaporu unite in Tarsila’s final great painting, Antropofagia, a marriage of two figures that is also a marriage of Old World and New. The couple sit entangled, her breast drooping over his knee, their giant feet crossed one over the other, while, behind them, a banana leaf grows as large as a cactus. The sun, high above the primordial couple, is a wedge of lemon.

(Jason Farago. www.nytimes.com, 15.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o trecho do artigo de Jason Farago, publicado pelo jornal The New York Times, para responder às questões

She led Latin American Art in a bold new direction

In 1928, Tarsila do Amaral painted Abaporu, a landmark work of Brazilian Modernism, in which a nude figure, half-human and half-animal, looks down at his massive, swollen foot, several times the size of his head. Abaporu inspired Tarsila’s husband at the time, the poet Oswald de Andrade, to write his celebrated “Cannibal Manifesto,” which flayed Brazil’s belletrist writers and called for an embrace of local influences – in fact, for a devouring of them. The European stereotype of native Brazilians as cannibals would be reformatted as a cultural virtue. More than a social and literary reform movement, cannibalism would form the basis for a new Brazilian nationalism, in which, as de Andrade wrote, “we made Christ to be born in Bahia.”

The unconventional nudes of A Negra, a painting produced in 1923, and Abaporu unite in Tarsila’s final great painting, Antropofagia, a marriage of two figures that is also a marriage of Old World and New. The couple sit entangled, her breast drooping over his knee, their giant feet crossed one over the other, while, behind them, a banana leaf grows as large as a cactus. The sun, high above the primordial couple, is a wedge of lemon.

(Jason Farago. www.nytimes.com, 15.02.2018. Adaptado.)

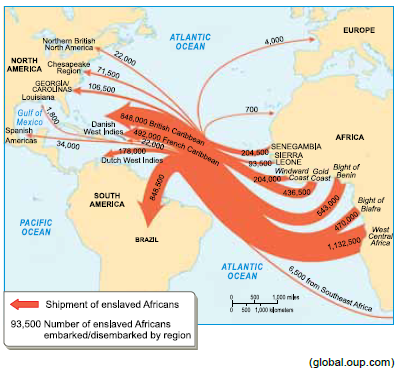

Based on the information presented by the map, one can say that, from 1731 to 1775,

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

– São uma formosura os governantes que tu modelaste, como se fosses um estatuário, ó Sócrates! [...]

– Ora pois! Concordais que não são inteiramente utopias o que estivemos a dizer sobre a cidade e a constituição; que, embora difíceis, eram de algum modo possíveis, mas não de outra maneira que não seja a que dissemos, quando os governantes, um ou vários, forem filósofos verdadeiros, que desprezem as honrarias atuais, por as considerarem impróprias de um homem livre e destituídas de valor, mas, por outro lado, que atribuem a máxima importância à retidão e às honrarias que dela derivam, e consideram o mais alto e o mais necessário dos bens a justiça, à qual servirão e farão prosperar, organizando assim a sua cidade?

(Platão. A República, 1987.)

O texto, concluído na primeira metade do século IV a.C.,

caracteriza

(Georges Duby. Damas do século XII:

a lembrança das ancestrais, 1997. Adaptado.)

O texto trata de relações desenvolvidas num meio social específico, durante a Idade Média ocidental. Nele,

(Eduardo Natalino dos Santos.

Cidades pré-hispânicas do México e da América Central, 2004.)

As cidades existentes na América Central e no México no período pré-colombiano

(Frei Vicente do Salvador, 1627. Apud Laura de Mello e Souza.

O Diabo e a Terra de Santa Cruz, 1986. Adaptado.)

O texto revela que

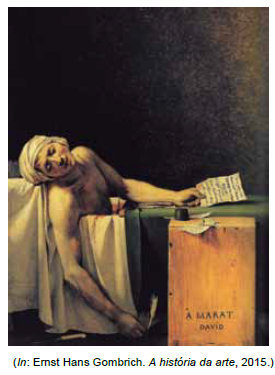

Analise a tela Marat assassinado, pintada por Jacques-Louis David em 1793.

Essa pintura apresenta estilo

Um homem transporta o fio metálico, outro endireita-o, um terceiro corta-o, um quarto aguça a extremidade, um quinto prepara a extremidade superior para receber a cabeça; para fazer a cabeça são precisas duas ou três operações distintas; colocá-la constitui também uma tarefa específica, branquear o alfinete, outra; colocar os alfinetes sobre o papel da embalagem é também uma tarefa independente. [...] Tive ocasião de ver uma pequena fábrica deste tipo, em que só estavam empregados dez homens, e onde alguns deles, consequentemente, realizavam duas ou três operações diferentes. Mas, apesar de serem muito pobres, e possuindo apenas a maquinaria estritamente necessária, [...] conseguiam produzir mais de quarenta e oito mil alfinetes por dia. Se dividirmos esse trabalho pelo número de trabalhadores, poderemos considerar que cada um deles produz quatro mil e oitocentos alfinetes por dia; mas se trabalhassem separadamente uns dos outros, e sem terem sido educados para este ramo particular de produção, não conseguiriam produzir vinte alfinetes, nem talvez mesmo um único alfinete por dia.

(Adam Smith. Investigação sobre a natureza

e as causas da riqueza das nações, 1984.)

O texto, originalmente publicado em 1776, demonstra

(Sérgio Buarque de Holanda. Raízes do Brasil, 1987.)

O “caráter próprio” das fazendas de café do Oeste paulista de 1840 pode ser explicado, em parte, pelo

O mapa representa a divisão da África no final do século XIX.

Essa divisão

Leia o poema “Pobre alimária”, de Oswald de Andrade, publicado originalmente em 1925.

O cavalo e a carroça

Estavam atravancados no trilho

E como o motorneiro se impacientasse

Porque levava os advogados para os escritórios

Desatravancaram o veículo

E o animal disparou

Mas o lesto carroceiro

Trepou na boleia

E castigou o fugitivo atrelado

Com um grandioso chicote

(Pau-Brasil, 1990.)

Considerando o momento de sua produção, o poema

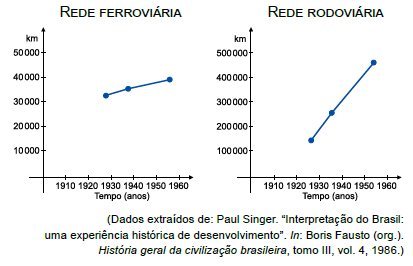

As informações dos dois gráficos estão traduzidas na tabela: