Questões de Vestibular UEA 2019 para Prova de Conhecimentos Gerais

Foram encontradas 84 questões

E assim se passava o tempo para a moça esta. Assoava o nariz na barra da combinação. Não tinha aquela coisa delicada que se chama encanto. Só eu a vejo encantadora. Só eu, seu autor, a amo. Sofro por ela. E só eu é que posso dizer assim: “que é que você me pede chorando que eu não lhe dê cantando”? Essa moça não sabia que ela era o que era, assim como um cachorro não sabe que é cachorro. Daí não se sentir infeliz. A única coisa que queria era viver. Não sabia para quê, não se indagava. Quem sabe, achava que havia uma gloriazinha em viver. Ela pensava que a pessoa é obrigada a ser feliz. Então era. Antes de nascer ela era uma ideia? Antes de nascer ela era morta? E depois de nascer ela ia morrer? Mas que fina talhada de melancia.

E assim se passava o tempo para a moça esta. Assoava o nariz na barra da combinação. Não tinha aquela coisa delicada que se chama encanto. Só eu a vejo encantadora. Só eu, seu autor, a amo. Sofro por ela. E só eu é que posso dizer assim: “que é que você me pede chorando que eu não lhe dê cantando”? Essa moça não sabia que ela era o que era, assim como um cachorro não sabe que é cachorro. Daí não se sentir infeliz. A única coisa que queria era viver. Não sabia para quê, não se indagava. Quem sabe, achava que havia uma gloriazinha em viver. Ela pensava que a pessoa é obrigada a ser feliz. Então era. Antes de nascer ela era uma ideia? Antes de nascer ela era morta? E depois de nascer ela ia morrer? Mas que fina talhada de melancia.

E assim se passava o tempo para a moça esta. Assoava o nariz na barra da combinação. Não tinha aquela coisa delicada que se chama encanto. Só eu a vejo encantadora. Só eu, seu autor, a amo. Sofro por ela. E só eu é que posso dizer assim: “que é que você me pede chorando que eu não lhe dê cantando”? Essa moça não sabia que ela era o que era, assim como um cachorro não sabe que é cachorro. Daí não se sentir infeliz. A única coisa que queria era viver. Não sabia para quê, não se indagava. Quem sabe, achava que havia uma gloriazinha em viver. Ela pensava que a pessoa é obrigada a ser feliz. Então era. Antes de nascer ela era uma ideia? Antes de nascer ela era morta? E depois de nascer ela ia morrer? Mas que fina talhada de melancia.

E assim se passava o tempo para a moça esta. Assoava o nariz na barra da combinação. Não tinha aquela coisa delicada que se chama encanto. Só eu a vejo encantadora. Só eu, seu autor, a amo. Sofro por ela. E só eu é que posso dizer assim: “que é que você me pede chorando que eu não lhe dê cantando”? Essa moça não sabia que ela era o que era, assim como um cachorro não sabe que é cachorro. Daí não se sentir infeliz. A única coisa que queria era viver. Não sabia para quê, não se indagava. Quem sabe, achava que havia uma gloriazinha em viver. Ela pensava que a pessoa é obrigada a ser feliz. Então era. Antes de nascer ela era uma ideia? Antes de nascer ela era morta? E depois de nascer ela ia morrer? Mas que fina talhada de melancia.

O termo sublinhado exerce a função de predicativo do sujeito em:

Wood wide web: trees’ social networks are mapped

Research has shown that beneath every forest and wood there is a complex underground web of roots, fungi and bacteria helping to connect trees and plants to one another. This subterranean social network, nearly 500 million years old, has become known as the “wood wide web”. Now, an international study has produced the first global map of the “mycorrhizal fungi networks” dominating this secretive world.

Using machine-learning, researchers from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Stanford University in the US used the database of the Global Forest Initiative, which covers 1.2 million forest tree plots with 28,000 species, from more than 70 countries. Using millions of direct observations of trees and their symbiotic associations on the ground, the researchers could build models from the bottom up to visualise these fungal networks for the first time. Prof Thomas Crowther, one of the authors of the report, told the BBC, “It’s the first time that we’ve been able to understand the world beneath our feet, but at a global scale.”

The research reveals how important mycorrhizal networks are to limiting climate change — and how vulnerable they are to the effects of it. “Just like an Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan of the brain helps us to understand how the brain works, this global map of the fungi beneath the soil helps us to understand how global ecosystems work,” said Prof Crowther. “What we find is that certain types of microorganisms live in certain parts of the world, and by understanding that we can figure out how to restore different types of ecosystems and also how the climate is changing.” Losing chunks of the wood wide web could well increase “the feedback loop of warming temperatures and carbon emissions.”

Mycorrhizal fungi are those that form a symbiotic relationship with plants. There are two main groups of mycorrhizal fungi: arbuscular fungi (AM) that penetrate the host’s roots, and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) which surround the tree’s roots without penetrating them.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

Wood wide web: trees’ social networks are mapped

Research has shown that beneath every forest and wood there is a complex underground web of roots, fungi and bacteria helping to connect trees and plants to one another. This subterranean social network, nearly 500 million years old, has become known as the “wood wide web”. Now, an international study has produced the first global map of the “mycorrhizal fungi networks” dominating this secretive world.

Using machine-learning, researchers from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Stanford University in the US used the database of the Global Forest Initiative, which covers 1.2 million forest tree plots with 28,000 species, from more than 70 countries. Using millions of direct observations of trees and their symbiotic associations on the ground, the researchers could build models from the bottom up to visualise these fungal networks for the first time. Prof Thomas Crowther, one of the authors of the report, told the BBC, “It’s the first time that we’ve been able to understand the world beneath our feet, but at a global scale.”

The research reveals how important mycorrhizal networks are to limiting climate change — and how vulnerable they are to the effects of it. “Just like an Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan of the brain helps us to understand how the brain works, this global map of the fungi beneath the soil helps us to understand how global ecosystems work,” said Prof Crowther. “What we find is that certain types of microorganisms live in certain parts of the world, and by understanding that we can figure out how to restore different types of ecosystems and also how the climate is changing.” Losing chunks of the wood wide web could well increase “the feedback loop of warming temperatures and carbon emissions.”

Mycorrhizal fungi are those that form a symbiotic relationship with plants. There are two main groups of mycorrhizal fungi: arbuscular fungi (AM) that penetrate the host’s roots, and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) which surround the tree’s roots without penetrating them.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

Wood wide web: trees’ social networks are mapped

Research has shown that beneath every forest and wood there is a complex underground web of roots, fungi and bacteria helping to connect trees and plants to one another. This subterranean social network, nearly 500 million years old, has become known as the “wood wide web”. Now, an international study has produced the first global map of the “mycorrhizal fungi networks” dominating this secretive world.

Using machine-learning, researchers from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Stanford University in the US used the database of the Global Forest Initiative, which covers 1.2 million forest tree plots with 28,000 species, from more than 70 countries. Using millions of direct observations of trees and their symbiotic associations on the ground, the researchers could build models from the bottom up to visualise these fungal networks for the first time. Prof Thomas Crowther, one of the authors of the report, told the BBC, “It’s the first time that we’ve been able to understand the world beneath our feet, but at a global scale.”

The research reveals how important mycorrhizal networks are to limiting climate change — and how vulnerable they are to the effects of it. “Just like an Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan of the brain helps us to understand how the brain works, this global map of the fungi beneath the soil helps us to understand how global ecosystems work,” said Prof Crowther. “What we find is that certain types of microorganisms live in certain parts of the world, and by understanding that we can figure out how to restore different types of ecosystems and also how the climate is changing.” Losing chunks of the wood wide web could well increase “the feedback loop of warming temperatures and carbon emissions.”

Mycorrhizal fungi are those that form a symbiotic relationship with plants. There are two main groups of mycorrhizal fungi: arbuscular fungi (AM) that penetrate the host’s roots, and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) which surround the tree’s roots without penetrating them.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

Wood wide web: trees’ social networks are mapped

Research has shown that beneath every forest and wood there is a complex underground web of roots, fungi and bacteria helping to connect trees and plants to one another. This subterranean social network, nearly 500 million years old, has become known as the “wood wide web”. Now, an international study has produced the first global map of the “mycorrhizal fungi networks” dominating this secretive world.

Using machine-learning, researchers from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Stanford University in the US used the database of the Global Forest Initiative, which covers 1.2 million forest tree plots with 28,000 species, from more than 70 countries. Using millions of direct observations of trees and their symbiotic associations on the ground, the researchers could build models from the bottom up to visualise these fungal networks for the first time. Prof Thomas Crowther, one of the authors of the report, told the BBC, “It’s the first time that we’ve been able to understand the world beneath our feet, but at a global scale.”

The research reveals how important mycorrhizal networks are to limiting climate change — and how vulnerable they are to the effects of it. “Just like an Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan of the brain helps us to understand how the brain works, this global map of the fungi beneath the soil helps us to understand how global ecosystems work,” said Prof Crowther. “What we find is that certain types of microorganisms live in certain parts of the world, and by understanding that we can figure out how to restore different types of ecosystems and also how the climate is changing.” Losing chunks of the wood wide web could well increase “the feedback loop of warming temperatures and carbon emissions.”

Mycorrhizal fungi are those that form a symbiotic relationship with plants. There are two main groups of mycorrhizal fungi: arbuscular fungi (AM) that penetrate the host’s roots, and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) which surround the tree’s roots without penetrating them.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

(Henri-Irénée Marrou. De la connaissance historique, 1975. Adaptado.)

Depreende-se do texto que as condições essenciais para a pesquisa histórica são

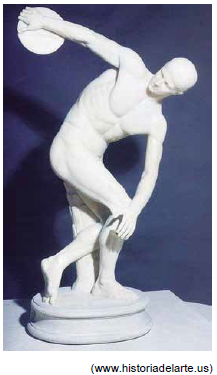

Pertencente ao Museu Nacional de Roma, o Discóbolo Lancellotti assinala

(Perry Anderson. Linhagens do Estado absolutista, 2016.)

O excerto do livro Linhagens do Estado absolutista descreve

(Dauril Alden. “O período final do Brasil colônia: 1750-1808” In: Leslie Bethell (org.). História da América Latina: a América Latina colonial, vol. II, 1999. Adaptado.)

O excerto faz uma descrição abrangente

(Luís Cláudio Villafañe Gomes Santos. O evangelho do Barão, 2012. Adaptado.)

O autor refere-se às negociações diplomáticas que deram origem ao Tratado de Petrópolis de 1903. A incorporação do Acre ao território brasileiro envolveu

O escritor Mário de Andrade fez uma viagem em comitiva à Amazônia e escreveu um diário sobre o périplo, que durou de 13 de maio a 15 de agosto de 1927. Leia alguns trechos desse diário.

Belém, 19 de maio

Depois do jantar, sem que fazer, fomos todos ao cinema

ver a fita importante que os jornais e as pessoas anunciavam,

William Fairbanks em Não percas tempo, filme horrível.

Manaus, 7 de junho.

De-noite, sem que fazer, fomos ao cinema. Levavam com

grande barulho de anúncio William Fairbanks em Não percas

tempo.

Iquitos, 25 de junho.

Me esqueci de contar: ontem, passeando, passamos

pelo cinema local que com grande estardalhaço anunciava

último dia do grande filme Não percas tempo com William

Fairbanks. É que o filme ia e vinha no navio conosco...

(Mário de Andrade. O turista aprendiz, 2002. Adaptado.)

[...] Vai, orgulhosa, querida Mas aceita esta lição: No câmbio incerto da vida A libra sempre é o coração O amor vem por princípio, a ordem por base O progresso é que deve vir por fim Desprezaste esta lei de Augusto Comte E foste ser feliz longe de mim [...] Vai, coração que não vibra Com teu juro exorbitante Transformar mais outra libra Em dívida flutuante [...]

(www.letras.mus.br)

A letra da música, apesar do seu lirismo irônico, refere-se à história do Brasil, caracterizada, em grande parte,

(Philip Jenkins. Breve historia de Estados Unidos, 2017. Adaptado.)

O excerto descreve a situação histórica dos Estados Unidos, marcada pela