Questões de Vestibular

Foram encontradas 68.627 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

If you take a look at my smartphone, you’ll know that I like to order out. But am I helping the small local businesses? You would think that if you own a restaurant you’d be thrilled to have an outsourced service that would take care of your delivery operations while leveraging their marketing might to expand your businesses’ brand. However, restaurant owners have complained of lack of quality control once their food goes out the door. They don’t like that the delivery people are the face of their product when it gets into the customer’s hand. Some of the delivery services have been accused of listing restaurants on their apps without the owners’ permission, and oftentimes publish menu items and prices that are incorrect or out of date.

But there is another reason why restaurant owners aren’t fond of delivery services. It’s the costs, which, for some, are becoming unsustainable. Even with the increased revenues from the delivery services, the fees wind up killing a restaurant’s margins to the extent that it’s at best marginally profitable. Therefore, some restaurants are pushing harder to drive orders from their own websites and offering special deals for customers that use their in-house delivery people.

The simple fact is that these delivery apps are here to stay. They are enormously popular and have significantly grown. I believe that restaurant owners that resist these apps are hurting their brands by missing out on potential customers. The good news is that the delivery platforms are not as evil as some would portray them. They have some skin in the game. They are competing against other services. They want their listed restaurants to profit. Maybe instead of fighting, the nation’s restaurant industry needs to proactively embrace the delivery service industry and figure out ways to profitably work together.

The Guardian. 02 December, 2020. Adaptado.

If you take a look at my smartphone, you’ll know that I like to order out. But am I helping the small local businesses? You would think that if you own a restaurant you’d be thrilled to have an outsourced service that would take care of your delivery operations while leveraging their marketing might to expand your businesses’ brand. However, restaurant owners have complained of lack of quality control once their food goes out the door. They don’t like that the delivery people are the face of their product when it gets into the customer’s hand. Some of the delivery services have been accused of listing restaurants on their apps without the owners’ permission, and oftentimes publish menu items and prices that are incorrect or out of date.

But there is another reason why restaurant owners aren’t fond of delivery services. It’s the costs, which, for some, are becoming unsustainable. Even with the increased revenues from the delivery services, the fees wind up killing a restaurant’s margins to the extent that it’s at best marginally profitable. Therefore, some restaurants are pushing harder to drive orders from their own websites and offering special deals for customers that use their in-house delivery people.

The simple fact is that these delivery apps are here to stay. They are enormously popular and have significantly grown. I believe that restaurant owners that resist these apps are hurting their brands by missing out on potential customers. The good news is that the delivery platforms are not as evil as some would portray them. They have some skin in the game. They are competing against other services. They want their listed restaurants to profit. Maybe instead of fighting, the nation’s restaurant industry needs to proactively embrace the delivery service industry and figure out ways to profitably work together.

The Guardian. 02 December, 2020. Adaptado.

If you take a look at my smartphone, you’ll know that I like to order out. But am I helping the small local businesses? You would think that if you own a restaurant you’d be thrilled to have an outsourced service that would take care of your delivery operations while leveraging their marketing might to expand your businesses’ brand. However, restaurant owners have complained of lack of quality control once their food goes out the door. They don’t like that the delivery people are the face of their product when it gets into the customer’s hand. Some of the delivery services have been accused of listing restaurants on their apps without the owners’ permission, and oftentimes publish menu items and prices that are incorrect or out of date.

But there is another reason why restaurant owners aren’t fond of delivery services. It’s the costs, which, for some, are becoming unsustainable. Even with the increased revenues from the delivery services, the fees wind up killing a restaurant’s margins to the extent that it’s at best marginally profitable. Therefore, some restaurants are pushing harder to drive orders from their own websites and offering special deals for customers that use their in-house delivery people.

The simple fact is that these delivery apps are here to stay. They are enormously popular and have significantly grown. I believe that restaurant owners that resist these apps are hurting their brands by missing out on potential customers. The good news is that the delivery platforms are not as evil as some would portray them. They have some skin in the game. They are competing against other services. They want their listed restaurants to profit. Maybe instead of fighting, the nation’s restaurant industry needs to proactively embrace the delivery service industry and figure out ways to profitably work together.

The Guardian. 02 December, 2020. Adaptado.

Fatbergs are a growing scourge infesting cities around the world— some are more than 800 feet long and weigh more than four humpback whales. These gross globs, which can cause sewer systems to block up and even overflow, have been plaguing the U.S., Great Britain and Australia for the past decade, forcing governments and utilities companies to send workers down into the sewers armed with water hoses, vacuums and scrapers with the unenviable task of prying them loose.

"It is hard not to think of [fatbergs] as a tangible symbol of the way we live now, the ultimate product of our disposable, out of sight, out of mind culture," wrote journalist Tim Adams in The Guardian.

At their core, fatbergs are the accumulation of oil and grease that's been poured down the drain, congealing around flushed nonbiological waste like tampons, condoms and baby wipes. When fat sticks to the side of sewage pipes, the wipes and other detritus get stuck, accumulating layer upon layer of gunk in a sort of slimy snowball effect.

Fatbergs also collect other kinds of debris—London fatbergs have been cracked open to reveal pens, false teeth and even watches.

Restaurants are a big contributor to fatbergs: Thames Water, the London utilities company, found nine out of 10 fast-food eateries lacked adequate grease traps to stop fat from entering the sewers. Homeowners also contribute to the problem by pouring grease and fat down the sink.

Even though its component materials are soft, fatbergs themselves can be tough as rocks. Researchers have found a host of dangerous bacteria in fatbergs, including listeria and e.coli.

Fatbergs are notorious for their fetid smell, which can make even the hardiest sewer workers gag, and chipping away at one can release noxious gases.

The key to fatberg prevention is remembering the four Ps: Pee, poo, puke and (toilet) paper are the only things that should be flushed.

Newsweek, 14 March, 2019. Adaptado.

Fatbergs are a growing scourge infesting cities around the world— some are more than 800 feet long and weigh more than four humpback whales. These gross globs, which can cause sewer systems to block up and even overflow, have been plaguing the U.S., Great Britain and Australia for the past decade, forcing governments and utilities companies to send workers down into the sewers armed with water hoses, vacuums and scrapers with the unenviable task of prying them loose.

"It is hard not to think of [fatbergs] as a tangible symbol of the way we live now, the ultimate product of our disposable, out of sight, out of mind culture," wrote journalist Tim Adams in The Guardian.

At their core, fatbergs are the accumulation of oil and grease that's been poured down the drain, congealing around flushed nonbiological waste like tampons, condoms and baby wipes. When fat sticks to the side of sewage pipes, the wipes and other detritus get stuck, accumulating layer upon layer of gunk in a sort of slimy snowball effect.

Fatbergs also collect other kinds of debris—London fatbergs have been cracked open to reveal pens, false teeth and even watches.

Restaurants are a big contributor to fatbergs: Thames Water, the London utilities company, found nine out of 10 fast-food eateries lacked adequate grease traps to stop fat from entering the sewers. Homeowners also contribute to the problem by pouring grease and fat down the sink.

Even though its component materials are soft, fatbergs themselves can be tough as rocks. Researchers have found a host of dangerous bacteria in fatbergs, including listeria and e.coli.

Fatbergs are notorious for their fetid smell, which can make even the hardiest sewer workers gag, and chipping away at one can release noxious gases.

The key to fatberg prevention is remembering the four Ps: Pee, poo, puke and (toilet) paper are the only things that should be flushed.

Newsweek, 14 March, 2019. Adaptado.

Fatbergs are a growing scourge infesting cities around the world— some are more than 800 feet long and weigh more than four humpback whales. These gross globs, which can cause sewer systems to block up and even overflow, have been plaguing the U.S., Great Britain and Australia for the past decade, forcing governments and utilities companies to send workers down into the sewers armed with water hoses, vacuums and scrapers with the unenviable task of prying them loose.

"It is hard not to think of [fatbergs] as a tangible symbol of the way we live now, the ultimate product of our disposable, out of sight, out of mind culture," wrote journalist Tim Adams in The Guardian.

At their core, fatbergs are the accumulation of oil and grease that's been poured down the drain, congealing around flushed nonbiological waste like tampons, condoms and baby wipes. When fat sticks to the side of sewage pipes, the wipes and other detritus get stuck, accumulating layer upon layer of gunk in a sort of slimy snowball effect.

Fatbergs also collect other kinds of debris—London fatbergs have been cracked open to reveal pens, false teeth and even watches.

Restaurants are a big contributor to fatbergs: Thames Water, the London utilities company, found nine out of 10 fast-food eateries lacked adequate grease traps to stop fat from entering the sewers. Homeowners also contribute to the problem by pouring grease and fat down the sink.

Even though its component materials are soft, fatbergs themselves can be tough as rocks. Researchers have found a host of dangerous bacteria in fatbergs, including listeria and e.coli.

Fatbergs are notorious for their fetid smell, which can make even the hardiest sewer workers gag, and chipping away at one can release noxious gases.

The key to fatberg prevention is remembering the four Ps: Pee, poo, puke and (toilet) paper are the only things that should be flushed.

Newsweek, 14 March, 2019. Adaptado.

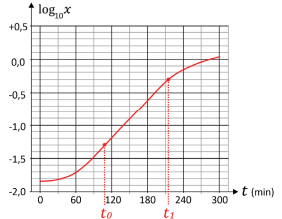

A quantidade de bactérias em um líquido é diretamente proporcional à medida da turbidez desse líquido. O gráfico mostra, em escala logarítmica, o crescimento da turbidez x de um líquido ao longo do tempo t (medido em minutos), isto é, mostra log10x em função de t. Os dados foram coletados de 30 em 30 minutos, e uma curva de interpolação foi obtida para inferir valores intermediários.

Disponível em https://fankhauserblog.wordpress.com/.

Com base no gráfico, em quantas vezes a população de

bactérias aumentou, do instante t0 para o instante t1?

Em fevereiro de 2021, um grupo de físicos da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) publicou um artigo que foi capa da importante revista Nature. O texto a seguir foi retirado de uma reportagem do site da UFMG sobre o artigo:

O nanoscópio, prossegue Ado Jorio (professor da UFMG), ilumina a amostra com um microscópio óptico usual. O foco da luz tem o tamanho de um círculo de 1 micrômetro de diâmetro. “O que o nanoscópio faz é inserir uma nanoantena, que tem uma ponta com diâmetro de 10 nanômetros, dentro desse foco de 1 micrômetro e escanear essa ponta. A imagem com resolução nanométrica é formada por esse processo de escaneamento da nanoantena, que localiza o campo eletromagnético da luz em seu ápice”, afirma o professor.

Itamar Rigueira Jr. “Nanoscópio da UFMG possibilita compreender estrutura que torna grafeno supercondutor”. Adaptado. Disponível em https://ufmg.br/comunicacao/noticias/. Gadelha A C et al. (2021), Nature, 590, 405-409, doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03252-5.

Com base nos dados mencionados no texto, a razão entre o diâmetro do foco da luz de um microscópio óptico usual e o diâmetro da ponta da nanoantena utilizada no nanoscópio é da ordem de:

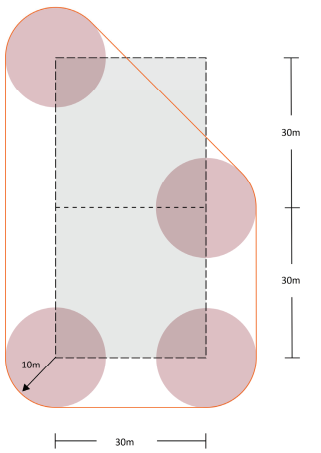

Quatro tanques cilíndricos são vistos de cima (em planta baixa) conforme a figura. Todos têm 10 m de raio e seus centros se posicionam em vértices dos dois quadrados tracejados adjacentes, ambos com 30 m de lado. Uma fita de isolamento, esticada e paralela ao solo, envolve os 4 tanques, dando uma volta completa (linha em laranja na figura).

O comprimento da fita, em metros, é:

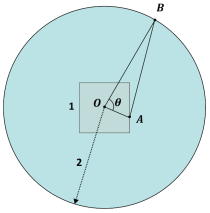

A figura mostra um quadrado e um círculo, ambos com centro no ponto O. O quadrado tem lado medindo 1 unidade de medida (u.m.) e o círculo tem raio igual a 2 u.m. O ponto A está sobre o contorno do quadrado, o ponto B está sobre o contorno do círculo, e o segmento AB tem tamanho 2 u.m.

Quando o ângulo θ = AÔB for máximo, seu cosseno será:

Note e adote: Em poliedros convexos, vale a relação de Euler F - A + V = 2, em que F é o número de faces, A é o número de arestas e V é o número de vértices do poliedro.

Uma indústria produz três modelos de cadeiras (indicadas por M1, M2 e M3), cada um deles em duas opções de cores: preta e vermelha (indicadas por P e V, respectivamente). A tabela mostra o número de cadeiras produzidas semanalmente conforme a cor e o modelo:

P V

M1 500 200

M2 400 220

M3 250 300

As porcentagens de cadeiras com defeito são de 2% do modelo M1, 5% do modelo M2 e 8% do modelo M3. As cadeiras que não apresentam defeito são denominadas boas.

A tabela que indica o número de cadeiras produzidas

semanalmente com defeito (D) e boas (B), de acordo com a

cor, é:

O sistema de numeração conhecido como chinês científico (ou em barras) surgiu provavelmente há mais de dois milênios. O sistema é essencialmente posicional, de base 10, com o primeiro algarismo à direita representando a unidade. A primeira linha horizontal de símbolos da figura mostra como se representam os algarismos 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 e 9 quando aparecem em posições ímpares (unidades, centenas etc.), e a segunda linha quando tais algarismos aparecem em posições pares (dezenas, milhares etc.). Nesse sistema, passou-se a usar um círculo para representar o algarismo zero a partir da Dinastia Sung (960-1126).

Howard Eves, Introdução à História da Matemática. Tradução: Hygino H.

Domingues. Editora Unicamp, 2011 (5ª ed.).

Assinale a alternativa que representa o número 91625 nesse

sistema de numeração.

Atualmente, no Brasil, coexistem dois sistemas de placas de identificação de automóveis: o padrão Mercosul (o mais recente) e aquele que se iniciou em 1990 (o sistema anterior, usado ainda pela maioria dos carros em circulação). No sistema anterior, utilizavam-se 3 letras (em um alfabeto de 26 letras) seguidas de 4 algarismos (de 0 a 9). No padrão Mercosul adotado no Brasil para automóveis, são usadas 4 letras e 3 algarismos, com 3 letras nas primeiras 3 posições e a quarta letra na quinta posição, podendo haver repetições de letras ou de números. A figura ilustra os dois tipos de placas.

Dessa forma, o número de placas possíveis do padrão Mercosul

brasileiro de automóveis é maior do que o do sistema anterior em

A escrita faz de tal modo parte de nossa civilização que poderia servir de definição dela própria. A história da humanidade se divide em duas imensas eras: antes e a partir da escrita. Talvez venha o dia de uma terceira era — depois da escrita. Vivemos os séculos da civilização escrita. Todas as nossas sociedades baseiam-se no escrito. A lei escrita substitui a lei oral, o contrato escrito substitui a convenção verbal, a religião escrita se seguiu à tradição lendária. E sobretudo não existe história que não se funde sobre textos.

Charles Higounet. A história da escrita. Adaptado.

A escrita faz de tal modo parte de nossa civilização que poderia servir de definição dela própria. A história da humanidade se divide em duas imensas eras: antes e a partir da escrita. Talvez venha o dia de uma terceira era — depois da escrita. Vivemos os séculos da civilização escrita. Todas as nossas sociedades baseiam-se no escrito. A lei escrita substitui a lei oral, o contrato escrito substitui a convenção verbal, a religião escrita se seguiu à tradição lendária. E sobretudo não existe história que não se funde sobre textos.

Charles Higounet. A história da escrita. Adaptado.