Questões de Vestibular

Foram encontradas 69.760 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

[Leonardo da Vinci] viu que “a água corrente detém em si um número infinito de movimentos”.

Um “número infinito”? Para Leonardo, não se trata apenas de uma figura de linguagem. Ao falar da variedade infinita da natureza e sobretudo de fenômenos como as correntes de água, ele estava fazendo uma distinção baseada na preferência por sistemas analógicos sobre os digitais. Em um sistema analógico, há gradações infinitas, o que se aplica à maioria das coisas que fascinavam Leonardo: sombras de sfumato, cores, movimento, ondas, a passagem do tempo, a dinâmica dos fluidos.

(Walter Isaacson. Leonardo da Vinci, 2017.)

A partir da explicação do texto sobre Leonardo da Vinci, pode-se afirmar que

Observe a imagem.

A Catedral de Notre-Dame, em Paris, parcialmente destruída por um incêndio em abril de 2019, é um exemplo da arquitetura

A Odisseia choca-se com a questão do passado. Para perscrutar o futuro e o passado, recorre-se geralmente ao adivinho. Inspirado pela musa, o adivinho vê o antes e o além: circula entre os deuses e entre os homens, não todos os homens, mas os heróis, preferencialmente mortos gloriosamente em combate. Ao celebrar aqueles que passaram, ele forja o passado, mas um passado sem duração, acabado.

(François Hartog. Regimes de historicidade:

presentismo e experiências do tempo, 2015. Adaptado.)

O texto afirma que a obra de Homero

Tate Modern – London

Hélio Oiticica

Until Summer 2019

Tropicália

Tropicália is used to describe the explosion of cultural creativity in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1968 as Brazil’s military regime tightened its grip on power.

Many of the artists, writers and musicians associated with Tropicália came of age during the 1950s in a time of intense optimism when the cultural world had been encouraged to play a central role in the creation of a democratic, socially just and modern Brazil. Nevertheless, a military coup in 1964 had brought to power a right-wing regime at odds with the concerns of left-wing artists. Tropicália became a way of exposing the contradictions of modernisation under such an authoritarian rule.

The word Tropicália comes from an installation by the artist Hélio Oiticica, who created environments that were designed to encourage the viewer’s emotional and intellectual participation. Oiticica called them “penetrables” because people were originally encouraged to enter them. They mimic the improvised, colourful dwellings in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shanty towns. The lush plants and sand help to convey a sense of the tropical character of the city. When Oiticica exhibited the work, he also included live parrots.

From its beginning, Tropicália was seen as a re-articulation of Anthropophagia (“cannibalism”), an artistic ideology promoted by Oswald de Andrade.

(www.tate.org.uk. Adaptado.)

Tate Modern – London

Hélio Oiticica

Until Summer 2019

Tropicália

Tropicália is used to describe the explosion of cultural creativity in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1968 as Brazil’s military regime tightened its grip on power.

Many of the artists, writers and musicians associated with Tropicália came of age during the 1950s in a time of intense optimism when the cultural world had been encouraged to play a central role in the creation of a democratic, socially just and modern Brazil. Nevertheless, a military coup in 1964 had brought to power a right-wing regime at odds with the concerns of left-wing artists. Tropicália became a way of exposing the contradictions of modernisation under such an authoritarian rule.

The word Tropicália comes from an installation by the artist Hélio Oiticica, who created environments that were designed to encourage the viewer’s emotional and intellectual participation. Oiticica called them “penetrables” because people were originally encouraged to enter them. They mimic the improvised, colourful dwellings in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shanty towns. The lush plants and sand help to convey a sense of the tropical character of the city. When Oiticica exhibited the work, he also included live parrots.

From its beginning, Tropicália was seen as a re-articulation of Anthropophagia (“cannibalism”), an artistic ideology promoted by Oswald de Andrade.

(www.tate.org.uk. Adaptado.)

Tate Modern – London

Hélio Oiticica

Until Summer 2019

Tropicália

Tropicália is used to describe the explosion of cultural creativity in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1968 as Brazil’s military regime tightened its grip on power.

Many of the artists, writers and musicians associated with Tropicália came of age during the 1950s in a time of intense optimism when the cultural world had been encouraged to play a central role in the creation of a democratic, socially just and modern Brazil. Nevertheless, a military coup in 1964 had brought to power a right-wing regime at odds with the concerns of left-wing artists. Tropicália became a way of exposing the contradictions of modernisation under such an authoritarian rule.

The word Tropicália comes from an installation by the artist Hélio Oiticica, who created environments that were designed to encourage the viewer’s emotional and intellectual participation. Oiticica called them “penetrables” because people were originally encouraged to enter them. They mimic the improvised, colourful dwellings in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shanty towns. The lush plants and sand help to convey a sense of the tropical character of the city. When Oiticica exhibited the work, he also included live parrots.

From its beginning, Tropicália was seen as a re-articulation of Anthropophagia (“cannibalism”), an artistic ideology promoted by Oswald de Andrade.

(www.tate.org.uk. Adaptado.)

Tate Modern – London

Hélio Oiticica

Until Summer 2019

Tropicália

Tropicália is used to describe the explosion of cultural creativity in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1968 as Brazil’s military regime tightened its grip on power.

Many of the artists, writers and musicians associated with Tropicália came of age during the 1950s in a time of intense optimism when the cultural world had been encouraged to play a central role in the creation of a democratic, socially just and modern Brazil. Nevertheless, a military coup in 1964 had brought to power a right-wing regime at odds with the concerns of left-wing artists. Tropicália became a way of exposing the contradictions of modernisation under such an authoritarian rule.

The word Tropicália comes from an installation by the artist Hélio Oiticica, who created environments that were designed to encourage the viewer’s emotional and intellectual participation. Oiticica called them “penetrables” because people were originally encouraged to enter them. They mimic the improvised, colourful dwellings in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shanty towns. The lush plants and sand help to convey a sense of the tropical character of the city. When Oiticica exhibited the work, he also included live parrots.

From its beginning, Tropicália was seen as a re-articulation of Anthropophagia (“cannibalism”), an artistic ideology promoted by Oswald de Andrade.

(www.tate.org.uk. Adaptado.)

Analyse the following comic.

(http://iniscommunication.com)

The objective of the comic is to

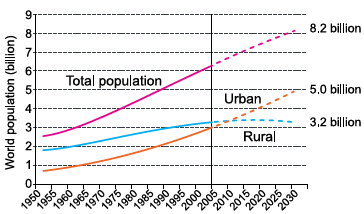

The future is largely urban

By 2030, there will be 5 billion people living in

urban areas (61% of the estimated world

population of 8.2 billion)

(http://esa.un.org. Adaptado.)

The chart shows that the approximate period of time when both urban and rural estimated populations were equal was

Cerrado

Located between the Amazon, Atlantic Forests and Pantanal, the Cerrado is the largest savanna region in South America.

The Cerrado is one of the most threatened and overexploited regions in Brazil, second only to the Atlantic Forests in vegetation loss and deforestation. Unsustainable agricultural activities, particularly soy production and cattle ranching, as well as burning of vegetation for charcoal, continue to pose a major threat to the Cerrado’s biodiversity. Despite its environmental importance, it is one of the least protected regions in Brazil.

Facts & Figures

• Covering 2 million km2 , or 21% of the country’s territory, the Cerrado is the second largest vegetation type in Brazil.

• The area is equivalent to the size of England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

• More than 1,600 species of mammals, birds and reptiles have been identified in the Cerrado.

• Annual rainfall is around 800 to 1600 mm.

• The capital of Brazil, Brasilia, is located in the heart of the Cerrado. • Only 20% of the Cerrado’s original vegetation remains intact; less than 3% of the area is currently guarded by law.

(http://wwf.panda.org. Adaptado.)

Cerrado

Located between the Amazon, Atlantic Forests and Pantanal, the Cerrado is the largest savanna region in South America.

The Cerrado is one of the most threatened and overexploited regions in Brazil, second only to the Atlantic Forests in vegetation loss and deforestation. Unsustainable agricultural activities, particularly soy production and cattle ranching, as well as burning of vegetation for charcoal, continue to pose a major threat to the Cerrado’s biodiversity. Despite its environmental importance, it is one of the least protected regions in Brazil.

Facts & Figures

• Covering 2 million km2 , or 21% of the country’s territory, the Cerrado is the second largest vegetation type in Brazil.

• The area is equivalent to the size of England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

• More than 1,600 species of mammals, birds and reptiles have been identified in the Cerrado.

• Annual rainfall is around 800 to 1600 mm.

• The capital of Brazil, Brasilia, is located in the heart of the Cerrado. • Only 20% of the Cerrado’s original vegetation remains intact; less than 3% of the area is currently guarded by law.

(http://wwf.panda.org. Adaptado.)

Cerrado

Located between the Amazon, Atlantic Forests and Pantanal, the Cerrado is the largest savanna region in South America.

The Cerrado is one of the most threatened and overexploited regions in Brazil, second only to the Atlantic Forests in vegetation loss and deforestation. Unsustainable agricultural activities, particularly soy production and cattle ranching, as well as burning of vegetation for charcoal, continue to pose a major threat to the Cerrado’s biodiversity. Despite its environmental importance, it is one of the least protected regions in Brazil.

Facts & Figures

• Covering 2 million km2 , or 21% of the country’s territory, the Cerrado is the second largest vegetation type in Brazil.

• The area is equivalent to the size of England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

• More than 1,600 species of mammals, birds and reptiles have been identified in the Cerrado.

• Annual rainfall is around 800 to 1600 mm.

• The capital of Brazil, Brasilia, is located in the heart of the Cerrado. • Only 20% of the Cerrado’s original vegetation remains intact; less than 3% of the area is currently guarded by law.

(http://wwf.panda.org. Adaptado.)

Cerrado

Located between the Amazon, Atlantic Forests and Pantanal, the Cerrado is the largest savanna region in South America.

The Cerrado is one of the most threatened and overexploited regions in Brazil, second only to the Atlantic Forests in vegetation loss and deforestation. Unsustainable agricultural activities, particularly soy production and cattle ranching, as well as burning of vegetation for charcoal, continue to pose a major threat to the Cerrado’s biodiversity. Despite its environmental importance, it is one of the least protected regions in Brazil.

Facts & Figures

• Covering 2 million km2 , or 21% of the country’s territory, the Cerrado is the second largest vegetation type in Brazil.

• The area is equivalent to the size of England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

• More than 1,600 species of mammals, birds and reptiles have been identified in the Cerrado.

• Annual rainfall is around 800 to 1600 mm.

• The capital of Brazil, Brasilia, is located in the heart of the Cerrado. • Only 20% of the Cerrado’s original vegetation remains intact; less than 3% of the area is currently guarded by law.

(http://wwf.panda.org. Adaptado.)

(Ian Chilvers (org.). Dicionário Oxford de arte, 2007.)

Verificam-se distorções e ambiguidades em relação à técnica da perspectiva na seguinte obra:

Tal movimento distingue-se pela atenuação do sentimentalismo e da melancolia, a ausência quase completa de interesse político no contexto da obra (embora não na conduta) e (como os modelos franceses) pelo cuidado da escrita, aspirando a uma expressão de tipo plástico. O mito da pureza da língua, do casticismo vernacular abonado pela autoridade dos autores clássicos, empolgou toda essa fase da cultura brasileira e foi um critério de excelência. É possível mesmo perguntar se a visão luxuosa dos autores desse movimento não representava para as classes dominantes uma espécie de correlativo da prosperidade material e, para o comum dos leitores, uma miragem compensadora que dava conforto.

(Antonio Candido. Iniciação à literatura brasileira, 2010. Adaptado.)

O texto refere-se ao movimento denominado

Examine o cartum de Pia Guerra, publicado no Instagram da revista The New Yorker em 13.11.2018.

“I had that dream again where the small hairy creatures were selling my body for three dollars a gallon.”

A mercadoria a que o cartum faz alusão está diretamente relacionada ao seguinte problema ambiental:

— […] O encontro de duas expansões, ou a expansão de duas formas, pode determinar a supressão de uma delas; mas, rigorosamente, não há morte, há vida, porque a supressão de uma é condição da sobrevivência da outra, e a destruição não atinge o princípio universal e comum. Daí o caráter conservador e benéfico da guerra. Supõe tu um campo de batatas e duas tribos famintas. As batatas apenas chegam para alimentar uma das tribos, que assim adquire forças para transpor a montanha e ir à outra vertente, onde há batatas em abundância; mas, se as duas tribos dividirem em paz as batatas do campo, não chegam a nutrir-se suficientemente e morrem de inanição. A paz, nesse caso, é a destruição; a guerra é a conservação. Uma das tribos extermina a outra e recolhe os despojos. Daí a alegria da vitória, os hinos, aclamações, recompensas públicas e todos os demais efeitos das ações bélicas. Se a guerra não fosse isso, tais demonstrações não chegariam a dar-se, pelo motivo real de que o homem só comemora e ama o que lhe é aprazível ou vantajoso, e pelo motivo racional de que nenhuma pessoa canoniza uma ação que virtualmente a destrói. Ao vencido, ódio ou compaixão; ao vencedor, as batatas. [...] Aparentemente, há nada mais contristador que uma dessas terríveis pestes que devastam um ponto do globo? E, todavia, esse suposto mal é um benefício, não só porque elimina os organismos fracos, incapazes de resistência, como porque dá lugar à observação, à descoberta da droga curativa. A higiene é filha de podridões seculares; devemo-la a milhões de corrompidos e infectos. Nada se perde, tudo é ganho.

(Quincas Borba, 2016.)

— […] O encontro de duas expansões, ou a expansão de duas formas, pode determinar a supressão de uma delas; mas, rigorosamente, não há morte, há vida, porque a supressão de uma é condição da sobrevivência da outra, e a destruição não atinge o princípio universal e comum. Daí o caráter conservador e benéfico da guerra. Supõe tu um campo de batatas e duas tribos famintas. As batatas apenas chegam para alimentar uma das tribos, que assim adquire forças para transpor a montanha e ir à outra vertente, onde há batatas em abundância; mas, se as duas tribos dividirem em paz as batatas do campo, não chegam a nutrir-se suficientemente e morrem de inanição. A paz, nesse caso, é a destruição; a guerra é a conservação. Uma das tribos extermina a outra e recolhe os despojos. Daí a alegria da vitória, os hinos, aclamações, recompensas públicas e todos os demais efeitos das ações bélicas. Se a guerra não fosse isso, tais demonstrações não chegariam a dar-se, pelo motivo real de que o homem só comemora e ama o que lhe é aprazível ou vantajoso, e pelo motivo racional de que nenhuma pessoa canoniza uma ação que virtualmente a destrói. Ao vencido, ódio ou compaixão; ao vencedor, as batatas. [...] Aparentemente, há nada mais contristador que uma dessas terríveis pestes que devastam um ponto do globo? E, todavia, esse suposto mal é um benefício, não só porque elimina os organismos fracos, incapazes de resistência, como porque dá lugar à observação, à descoberta da droga curativa. A higiene é filha de podridões seculares; devemo-la a milhões de corrompidos e infectos. Nada se perde, tudo é ganho.

(Quincas Borba, 2016.)

— […] O encontro de duas expansões, ou a expansão de duas formas, pode determinar a supressão de uma delas; mas, rigorosamente, não há morte, há vida, porque a supressão de uma é condição da sobrevivência da outra, e a destruição não atinge o princípio universal e comum. Daí o caráter conservador e benéfico da guerra. Supõe tu um campo de batatas e duas tribos famintas. As batatas apenas chegam para alimentar uma das tribos, que assim adquire forças para transpor a montanha e ir à outra vertente, onde há batatas em abundância; mas, se as duas tribos dividirem em paz as batatas do campo, não chegam a nutrir-se suficientemente e morrem de inanição. A paz, nesse caso, é a destruição; a guerra é a conservação. Uma das tribos extermina a outra e recolhe os despojos. Daí a alegria da vitória, os hinos, aclamações, recompensas públicas e todos os demais efeitos das ações bélicas. Se a guerra não fosse isso, tais demonstrações não chegariam a dar-se, pelo motivo real de que o homem só comemora e ama o que lhe é aprazível ou vantajoso, e pelo motivo racional de que nenhuma pessoa canoniza uma ação que virtualmente a destrói. Ao vencido, ódio ou compaixão; ao vencedor, as batatas. [...] Aparentemente, há nada mais contristador que uma dessas terríveis pestes que devastam um ponto do globo? E, todavia, esse suposto mal é um benefício, não só porque elimina os organismos fracos, incapazes de resistência, como porque dá lugar à observação, à descoberta da droga curativa. A higiene é filha de podridões seculares; devemo-la a milhões de corrompidos e infectos. Nada se perde, tudo é ganho.

(Quincas Borba, 2016.)

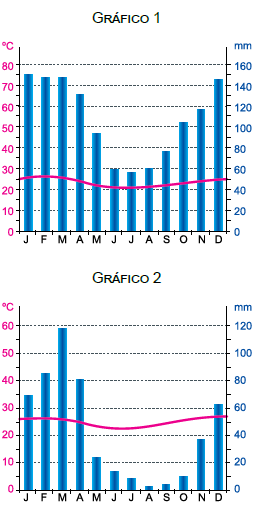

Examine os gráficos.

(http://pt.climate-data.org)

As dinâmicas climáticas representadas nos gráficos 1 e 2 correspondem, respectivamente, aos espaços retratados em