Questões Militares Comentadas sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 2.927 questões

I. O texto menciona preocupações relativas à privacidade e à discriminação como fatores complicadores na adoção da tecnologia pela polícia.

II. De acordo com o texto, as tecnologias emergentes estão a fomentar uma escalada na incidência de atividades criminosas.

III. Os leitores de placa, entre outras tecnologias, são mencionados no texto como ferramentas que auxiliam a polícia na redução de ferimentos e lesões corporais.

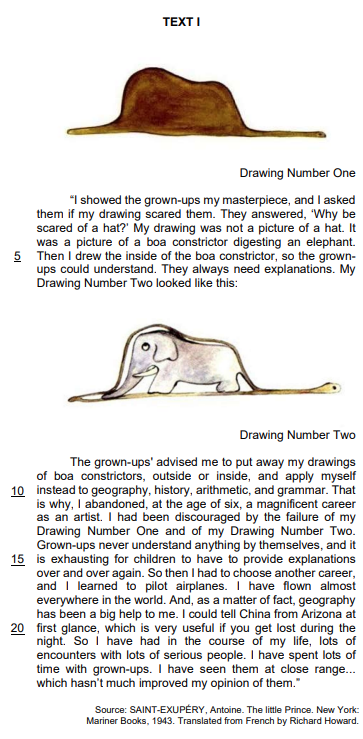

IV. O texto menciona que o Departamento de Polícia de Houston aumentou o seu efetivo para enfrentar os desafios impostos pela tecnologia.

De acordo com o texto I, está CORRETO afirmar que:

“I wanna leave my footprints on the sands of time” (l. 1) “Leave something to remember, so they won’t forget” (l. 5)

It’s possible to understand that

( ) one of them is afraid of death, the other treats the topic as ordinary.

( ) life’s unpredictability is seen as positive by one of the characters.

( ) according to the characters, life is more dangerous now than in the past.

( ) the man is skeptical whereas the duck is realistic.

( ) both characters are trying to cheer each other up.

Mark the correct option:

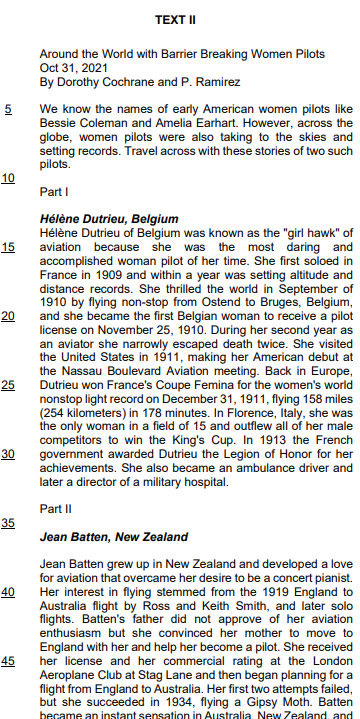

Check an event that is common for both texts:

Leia o texto e responda a questão.

Read the text and provide responses to question.

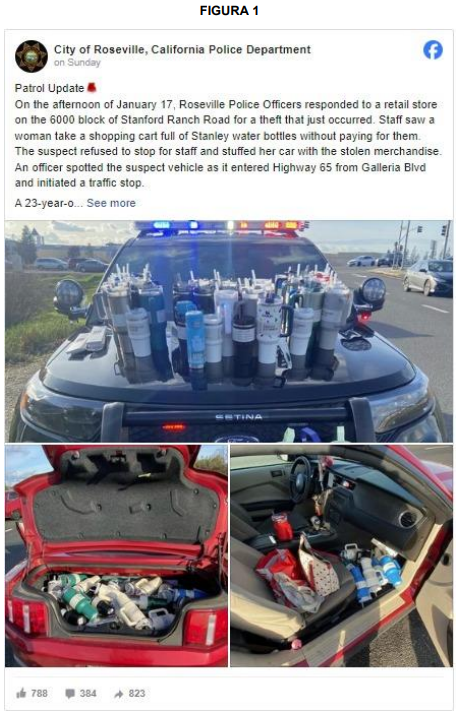

California woman arrested in theft of 65 Stanley cups - valued at nearly $2,500

By C Mandler

January 22, 2024 / 3:05 PM EST / CBS News

On Jan. 17, police in Roseville, California, discovered a 23-year-old woman had allegedly absconded with 65 Stanley cups from a nearby store — worth nearly $2,500.

"Staff saw a woman take a shopping cart full of Stanley water bottles without paying for them," said the Roseville Police Department in a statement on Facebook.

After being confronted by retail staff, the woman refused to stop, stuffing the cups into her car. She was subsequently arrested on a charge of grand theft and has yet to be identified by officers.

"While Stanley Quenchers are all the rage, we strongly advise against turning to crime to fulfill your hydration habits," said the Roseville police.

One commenter on the post pointed out that in addition to the trove of cups in the trunk and front seat, there was also a bright red Stanley cup in the cup holder, which they hoped police also confiscated. Colorful Stanley cups caused consumer mayhem earlier this month when the brand dropped a limited-edition batch of Valentine's Day colors of the popular tumbler at in-Target Starbucks locations.

Viral video showed shoppers running toward displays of the cups, as well as long lines of consumers waiting to get their hands on one of the coveted Quenchers.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/stanley-cups-theft-california-target-2500-65/ (First published on January 22, 2024 /3:05PM EST)

C Mandler is a social media producer and trending topics writer for CBS News, focusing on American politics and LGBTQ+ issues.

FIGURA 1

Fonte: CBS NEWS, 2024.

Leia o texto e responda a questão.

Read the text and provide responses to question.

California woman arrested in theft of 65 Stanley cups - valued at nearly $2,500

By C Mandler

January 22, 2024 / 3:05 PM EST / CBS News

On Jan. 17, police in Roseville, California, discovered a 23-year-old woman had allegedly absconded with 65 Stanley cups from a nearby store — worth nearly $2,500.

"Staff saw a woman take a shopping cart full of Stanley water bottles without paying for them," said the Roseville Police Department in a statement on Facebook.

After being confronted by retail staff, the woman refused to stop, stuffing the cups into her car. She was subsequently arrested on a charge of grand theft and has yet to be identified by officers.

"While Stanley Quenchers are all the rage, we strongly advise against turning to crime to fulfill your hydration habits," said the Roseville police.

One commenter on the post pointed out that in addition to the trove of cups in the trunk and front seat, there was also a bright red Stanley cup in the cup holder, which they hoped police also confiscated. Colorful Stanley cups caused consumer mayhem earlier this month when the brand dropped a limited-edition batch of Valentine's Day colors of the popular tumbler at in-Target Starbucks locations.

Viral video showed shoppers running toward displays of the cups, as well as long lines of consumers waiting to get their hands on one of the coveted Quenchers.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/stanley-cups-theft-california-target-2500-65/ (First published on January 22, 2024 /3:05PM EST)

C Mandler is a social media producer and trending topics writer for CBS News, focusing on American politics and LGBTQ+ issues.

FIGURA 1

Fonte: CBS NEWS, 2024.

Leia o texto e responda a questão.

Read the text and provide response to question.

California woman arrested in theft of 65 Stanley cups - valued at nearly $2,500

By C Mandler

January 22, 2024 / 3:05 PM EST / CBS News

On Jan. 17, police in Roseville, California, discovered a 23-year-old woman had allegedly absconded with 65 Stanley cups from a nearby store — worth nearly $2,500.

"Staff saw a woman take a shopping cart full of Stanley water bottles without paying for them," said the Roseville Police Department in a statement on Facebook.

After being confronted by retail staff, the woman refused to stop, stuffing the cups into her car. She was subsequently arrested on a charge of grand theft and has yet to be identified by officers.

"While Stanley Quenchers are all the rage, we strongly advise against turning to crime to fulfill your hydration habits," said the Roseville police.

One commenter on the post pointed out that in addition to the trove of cups in the trunk and front seat, there was also a bright red Stanley cup in the cup holder, which they hoped police also confiscated. Colorful Stanley cups caused consumer mayhem earlier this month when the brand dropped a limited-edition batch of Valentine's Day colors of the popular tumbler at in-Target Starbucks locations.

Viral video showed shoppers running toward displays of the cups, as well as long lines of consumers waiting to get their hands on one of the coveted Quenchers.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/stanley-cups-theft-california-target-2500-65/ (First published on January 22, 2024 /3:05PM EST)

C Mandler is a social media producer and trending topics writer for CBS News, focusing on American politics and LGBTQ+ issues.

FIGURA 1

Fonte: CBS NEWS, 2024.

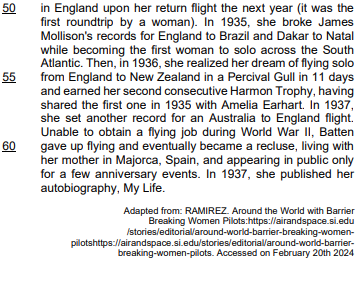

Why Climate Change Could Mean More Delayed Flights

No one enjoys a delayed flight, but as our weather gets warmer, we can expect more of them.

That's according to experts, who say that the heat of the summer might cause more delays.

Bloomberg looked at US data for flight delays at airports in Chicago and New York from June to August in 2022 and from January to March in 2023. It found that there were more delayed flights in the summer months at both airports.

When the temperature rises above 39 degrees Celsius, things get very difficult for airlines, Bijan Vasigh, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in the US, told Bloomberg.

The air is thinner when it gets hot and that makes it harder for planes to take off. In thinner air there is not as much lift, so more power is needed.

When they need more power, it helps to have a lighter airplane.

That might mean pilots have to make last-minute decisions to reduce the weight on board by dumping fuel, passengers or baggage — meaning the plane will probably be delayed.

The problem gets worse at airports that are at a higher altitude where the air is already thinner, and at airports with short runways, since planes need more space to get up to a high speed.

But thin air is not the only problem. Smoke from wildfires — that have been happening all around the world in the summer of 2023 — can also cause flights to be delayed and canceled.

Of course, the summer is also a busy time when millions of people fly, and weather is not the only cause of delays — but our hotter climate doesn't seem to be helping.

Internet: Engoo

Internet: BBC News

Internet: BBC News

Internet: BBC News

Internet: BBC News