Questões de Concurso Militar EsFCEx 2023 para Oficial - Magistério em Inglês

Foram encontradas 30 questões

There are three areas where our behaviour can directly influence our students’ continuing participation: goals and goal setting; learning environment; interesting classes.

(J. Harmer, The practice of English language teaching. 4th ed. Essex: Pearson Longman, 2007. Adaptado)

The task proposed in the last paragraph of the text on ChatGPT illustrates the following motivational behavior on the part of teachers:

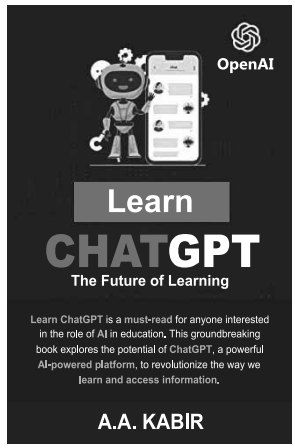

Read the cover of the book by A.A. Kabir.

(amazon.com)

Ajudar seu aluno a desenvolver a habilidade de leitura

em inglês significa, entre outros, ajudá-lo a comparar

diferentes textos. Ao confrontar o artigo sobre ChatGPT

e a capa do livro de A.A. Kabir, ele deverá perceber que

ambos mencionam

A exposição do autor no segundo parágrafo traz a seguinte implicação para o ensino de inglês no contexto brasileiro: