Questões Militares

Comentadas para vunesp

Foram encontradas 4.248 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Água (líquida) = 1 cal/gºC Alumínio (Al) = 0,22 cal/gºC Gelo = 0,50 cal/gºC Mercúrio (Hg) = 0,03 cal/gºC Areia = 0,12 cal/gºC Prata (Ag) = 0,05 cal/gºC Vidro = 0,20 cal/gºC Ferro (Fe) = 0,11 cal/gºC

Consultando a tabela, avalie as afirmativas a seguir.

I. A água, por ter um calor específico muito alto, é um excelente elemento termorregulador. A ausência de água faz com que, nos desertos, ocorram enormes diferenças entre a temperatura máxima e a mínima em um mesmo dia. II. Para refrigerar uma peça aquecida, é comum mergulhá-la em água. Será mais eficiente, para resfriá-la, mergulhá-la em mercúrio. Só não se faz isso porque, além de muito caro, seus vapores são extremamente tóxicos. III. Se cedermos a mesma quantidade de calor a amostras de massas iguais de alumínio e ferro, a temperatura da amostra de ferro aumentará o dobro do que aumenta a amostra de alumínio.

Está correto o que se afirma em

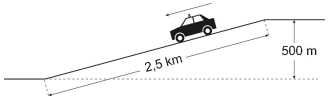

Ao longo da descida, ao ser atingida determinada velocidade, o motorista põe o carro em “ponto-morto”, para poupar combustível. Olhando para o velocímetro, o motorista percebe que o carro desce o restante da ladeira com velocidade constante. Suponha que a massa do carro com seus ocupantes e os equipamentos seja de 1200 kg e considere g = 10 m/s2. Tendo em conta as distâncias indicadas na figura, o módulo da resultante das diversas forças de atrito que se opõem ao movimento do carro, enquanto ele desce a ladeira com velocidade constante, é de

Considere a aceleração da gravidade constante e desprezível a resistência do ar.

Os gráficos que melhor representam como a energia cinética e a energia potencial gravitacional do projétil variam, em função de sua altura h durante a subida, são

com o elevador subindo em movimento

acelerado; uma força

com o elevador subindo em movimento

acelerado; uma força  com o elevador subindo em movimento

uniforme; e uma força

com o elevador subindo em movimento

uniforme; e uma força  com o elevador subindo em movimento

retardado.

com o elevador subindo em movimento

retardado. Essas forças

,

,  e

e  são tais que

são tais que O aquecimento será mais rápido se os resistores forem ligados à fonte de tensão, como apresentado no esquema

e um amperímetro (ideal)

e um amperímetro (ideal)

A maneira correta de ligar esses dispositivos para efetuar as medições está indicada no esquema

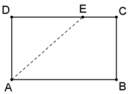

O ponto E do lado CD é tal que o segmento AE divide o retângulo em duas partes de forma que a área de uma seja o dobro da área da outra.

O segmento DE mede

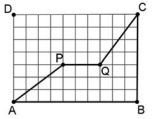

Dois soldados, Pedro e Paulo, caminharam de A até C por caminhos diferentes: Pedro percorreu os lados AB e BC, e Paulo percorreu os segmentos AP, PQ e QC.

É correto concluir que

A soma dos cubos das raízes dessa equação é

Sabe-se que, em abril, 400 policiais estiveram presentes no patrulhamento e 30 assaltos ocorreram, e que, em maio, o número de assaltos caiu para 24.

O número de policiais que estiveram presentes no patrulhamento no mês de maio foi

A capacidade desse tanque é de, aproximadamente,

Ao resolver certo problema, encontramos a equação exponencial ܽax =100.

Sabendo que o logaritmo decimal de ܽa é igual a 0,54, o valor de x é, aproximadamente,

O maior número de arrumações possíveis para esse retângulo de soldados é

Nessa cidade, de janeiro de 2020 para janeiro de 2021, com relação ao número de furtos de automóveis, houve

How facial recognition technology aids police

Police officers’ ability to recognize and locate individuals with a history of committing crime is vital to their work. In fact, it is so important that officers believe possessing it is fundamental to the craft of effective street policing, crime prevention and investigation. However, with the total police workforce falling by almost 20 percent since 2010 and recorded crime rising, police forces are turning to new technological solutions to help enhance their capability and capacity to monitor and track individuals about whom they have concerns.

One such technology is Automated Facial Recognition (known as AFR). This works by analyzing key facial features, generating a mathematical representation of them, and then comparing them against known faces in a database, to determine possible matches. While a number of UK and international police forces have been enthusiastically exploring the potential of AFR, some groups have spoken about its legal and ethical status. They are concerned that the technology significantly extends the reach and depth of surveillance by the state.

Until now, however, there has been no robust evidence about what AFR systems can and cannot deliver for policing. Although AFR has become increasingly familiar to the public through its use at airports to help manage passport checks, the environment in such settings is quite controlled. Applying similar procedures to street policing is far more complex. Individuals on the street will be moving and may not look directly towards the camera. Levels of lighting change, too, and the system will have to cope with the vagaries of the British weather.

[…]

As with all innovative policing technologies there are important legal and ethical concerns and issues that still need to be considered. But in order for these to be meaningfully debated and assessed by citizens, regulators and law-makers, we need a detailed understanding of precisely what the technology can realistically accomplish. Sound evidence, rather than references to science fiction technology --- as seen in films such as Minority Report --- is essential.

With this in mind, one of our conclusions is that in terms of describing how AFR is being applied in policing currently, it is more accurate to think of it as “assisted facial recognition,” as opposed to a fully automated system. Unlike border control functions -- where the facial recognition is more of an automated system -- when supporting street policing, the algorithm is not deciding whether there is a match between a person and what is stored in the database. Rather, the system makes suggestions to a police operator about possible similarities. It is then down to the operator to confirm or refute them.

By Bethan Davies, Andrew Dawson, Martin Innes

(Source: https://gcn.com/articles/2018/11/30/facial-recognitionpolicing.aspx, accessed May 30th, 2020)

How facial recognition technology aids police

Police officers’ ability to recognize and locate individuals with a history of committing crime is vital to their work. In fact, it is so important that officers believe possessing it is fundamental to the craft of effective street policing, crime prevention and investigation. However, with the total police workforce falling by almost 20 percent since 2010 and recorded crime rising, police forces are turning to new technological solutions to help enhance their capability and capacity to monitor and track individuals about whom they have concerns.

One such technology is Automated Facial Recognition (known as AFR). This works by analyzing key facial features, generating a mathematical representation of them, and then comparing them against known faces in a database, to determine possible matches. While a number of UK and international police forces have been enthusiastically exploring the potential of AFR, some groups have spoken about its legal and ethical status. They are concerned that the technology significantly extends the reach and depth of surveillance by the state.

Until now, however, there has been no robust evidence about what AFR systems can and cannot deliver for policing. Although AFR has become increasingly familiar to the public through its use at airports to help manage passport checks, the environment in such settings is quite controlled. Applying similar procedures to street policing is far more complex. Individuals on the street will be moving and may not look directly towards the camera. Levels of lighting change, too, and the system will have to cope with the vagaries of the British weather.

[…]

As with all innovative policing technologies there are important legal and ethical concerns and issues that still need to be considered. But in order for these to be meaningfully debated and assessed by citizens, regulators and law-makers, we need a detailed understanding of precisely what the technology can realistically accomplish. Sound evidence, rather than references to science fiction technology --- as seen in films such as Minority Report --- is essential.

With this in mind, one of our conclusions is that in terms of describing how AFR is being applied in policing currently, it is more accurate to think of it as “assisted facial recognition,” as opposed to a fully automated system. Unlike border control functions -- where the facial recognition is more of an automated system -- when supporting street policing, the algorithm is not deciding whether there is a match between a person and what is stored in the database. Rather, the system makes suggestions to a police operator about possible similarities. It is then down to the operator to confirm or refute them.

By Bethan Davies, Andrew Dawson, Martin Innes

(Source: https://gcn.com/articles/2018/11/30/facial-recognitionpolicing.aspx, accessed May 30th, 2020)

How facial recognition technology aids police

Police officers’ ability to recognize and locate individuals with a history of committing crime is vital to their work. In fact, it is so important that officers believe possessing it is fundamental to the craft of effective street policing, crime prevention and investigation. However, with the total police workforce falling by almost 20 percent since 2010 and recorded crime rising, police forces are turning to new technological solutions to help enhance their capability and capacity to monitor and track individuals about whom they have concerns.

One such technology is Automated Facial Recognition (known as AFR). This works by analyzing key facial features, generating a mathematical representation of them, and then comparing them against known faces in a database, to determine possible matches. While a number of UK and international police forces have been enthusiastically exploring the potential of AFR, some groups have spoken about its legal and ethical status. They are concerned that the technology significantly extends the reach and depth of surveillance by the state.

Until now, however, there has been no robust evidence about what AFR systems can and cannot deliver for policing. Although AFR has become increasingly familiar to the public through its use at airports to help manage passport checks, the environment in such settings is quite controlled. Applying similar procedures to street policing is far more complex. Individuals on the street will be moving and may not look directly towards the camera. Levels of lighting change, too, and the system will have to cope with the vagaries of the British weather.

[…]

As with all innovative policing technologies there are important legal and ethical concerns and issues that still need to be considered. But in order for these to be meaningfully debated and assessed by citizens, regulators and law-makers, we need a detailed understanding of precisely what the technology can realistically accomplish. Sound evidence, rather than references to science fiction technology --- as seen in films such as Minority Report --- is essential.

With this in mind, one of our conclusions is that in terms of describing how AFR is being applied in policing currently, it is more accurate to think of it as “assisted facial recognition,” as opposed to a fully automated system. Unlike border control functions -- where the facial recognition is more of an automated system -- when supporting street policing, the algorithm is not deciding whether there is a match between a person and what is stored in the database. Rather, the system makes suggestions to a police operator about possible similarities. It is then down to the operator to confirm or refute them.

By Bethan Davies, Andrew Dawson, Martin Innes

(Source: https://gcn.com/articles/2018/11/30/facial-recognitionpolicing.aspx, accessed May 30th, 2020)

How facial recognition technology aids police

Police officers’ ability to recognize and locate individuals with a history of committing crime is vital to their work. In fact, it is so important that officers believe possessing it is fundamental to the craft of effective street policing, crime prevention and investigation. However, with the total police workforce falling by almost 20 percent since 2010 and recorded crime rising, police forces are turning to new technological solutions to help enhance their capability and capacity to monitor and track individuals about whom they have concerns.

One such technology is Automated Facial Recognition (known as AFR). This works by analyzing key facial features, generating a mathematical representation of them, and then comparing them against known faces in a database, to determine possible matches. While a number of UK and international police forces have been enthusiastically exploring the potential of AFR, some groups have spoken about its legal and ethical status. They are concerned that the technology significantly extends the reach and depth of surveillance by the state.

Until now, however, there has been no robust evidence about what AFR systems can and cannot deliver for policing. Although AFR has become increasingly familiar to the public through its use at airports to help manage passport checks, the environment in such settings is quite controlled. Applying similar procedures to street policing is far more complex. Individuals on the street will be moving and may not look directly towards the camera. Levels of lighting change, too, and the system will have to cope with the vagaries of the British weather.

[…]

As with all innovative policing technologies there are important legal and ethical concerns and issues that still need to be considered. But in order for these to be meaningfully debated and assessed by citizens, regulators and law-makers, we need a detailed understanding of precisely what the technology can realistically accomplish. Sound evidence, rather than references to science fiction technology --- as seen in films such as Minority Report --- is essential.

With this in mind, one of our conclusions is that in terms of describing how AFR is being applied in policing currently, it is more accurate to think of it as “assisted facial recognition,” as opposed to a fully automated system. Unlike border control functions -- where the facial recognition is more of an automated system -- when supporting street policing, the algorithm is not deciding whether there is a match between a person and what is stored in the database. Rather, the system makes suggestions to a police operator about possible similarities. It is then down to the operator to confirm or refute them.

By Bethan Davies, Andrew Dawson, Martin Innes

(Source: https://gcn.com/articles/2018/11/30/facial-recognitionpolicing.aspx, accessed May 30th, 2020)