Questões Militares

Para pm-sp

Foram encontradas 5.471 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

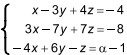

O sistema linear  terá solução somente quando o valor de α for igual

terá solução somente quando o valor de α for igual

Sobre um mapa de uma região, foi aplicado um sistema de coordenadas cartesianas, em que cada segmento de medida unitária, nesse sistema, correspondia a 1,5 quilômetros reais e, nesse sistema, duas praças foram identificadas com as coordenadas (1, –3) e (4, 1).

A distância real, em linha reta, em quilômetros, entre essas praças é de

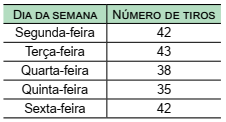

A tabela apresenta o número de tiros que uma pessoa deu nos 5 dias que treinou em um clube de tiros.

Naquela semana, a média aritmética diária de tiros que essa

pessoa deu, nesse clube, foi

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

America’s deadliest building fire for more than a decade struck Oakland, California, on December 2nd 2016, killing 36 people attending a dance party in a warehouse that had become a cluttered artist collective. The disaster highlights an open secret: many cities lack resources to inspect for fire risk all the structures that they should. Even though the Oakland building had no fire sprinklers and at least ten people lived there illegally, no inspector had visited in about 30 years. How might cities make better use of the inspectors they do have?

A handful of American cities have begun to seek help from a new type of analytics software. By crunching diverse data collected by government bodies and utilities, the software works out which buildings are most likely to catch fire and should therefore be inspected first. Plenty of factors play a role. Older, wooden buildings, unsurprisingly, pose more risk, as do those close to past fires and leaks of gas or oil. Poverty also pushes up fire risk, especially if lots of children, who may be attracted to mischief, live nearby. More telling are unpaid taxes, foreclosure proceedings and recorded complaints of mould, rats, crumbling plaster, accumulating rubbish, and domestic fights, all of which hint at property neglect. A building’s fire risk also increases the further it is from its owner’s residence.

Predictive software designed at Harvard that Portland, Oregon, will soon begin using will do that. Perhaps more importantly, the city’s fire chief noticed that buildings marked as being the biggest risks are clustered in areas lacking good schools, public transport, health care and food options. Healthier, happier people start fewer fires, he concluded. He now lobbies officials to reduce Portland’s pockets of deteriorated areas.

(The Economist. www.economist.com/the-economist-explains

/2018/08/29/how-cities-can-better-prevent-fires. Adaptado)

Leia o poema de Ricardo Reis, heterônimo de Fernando Pessoa, para responder às questões de números 53 e 54.

Já sobre a fronte vã se me acinzenta

O cabelo do jovem que perdi.

Meus olhos brilham menos,

Já não tem jus a beijos minha boca.

Se me ainda amas, por amor não ames:

Traíras-me comigo.

(Obra poética. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 1995, p. 279)

Leia o poema de Ricardo Reis, heterônimo de Fernando Pessoa, para responder às questões de números 53 e 54.

Já sobre a fronte vã se me acinzenta

O cabelo do jovem que perdi.

Meus olhos brilham menos,

Já não tem jus a beijos minha boca.

Se me ainda amas, por amor não ames:

Traíras-me comigo.

(Obra poética. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 1995, p. 279)

Leia o trecho de Dom Casmurro, de Machado de Assis, para responder à questão.

A imagem de Capitu ia comigo, e a minha imaginação, assim como lhe atribuíra lágrimas, há pouco, assim lhe encheu a boca de riso agora: vi-a escrever no muro, falar-me, andar à volta, com os braços no ar; ouvi distintamente o meu nome, de uma doçura que me embriagou, e a voz era dela.

(Obra completa. Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 1992, p. 840)

Leia o trecho de Dom Casmurro, de Machado de Assis, para responder à questão.

A imagem de Capitu ia comigo, e a minha imaginação, assim como lhe atribuíra lágrimas, há pouco, assim lhe encheu a boca de riso agora: vi-a escrever no muro, falar-me, andar à volta, com os braços no ar; ouvi distintamente o meu nome, de uma doçura que me embriagou, e a voz era dela.

(Obra completa. Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 1992, p. 840)

Leia o trecho de Dom Casmurro, de Machado de Assis, para responder à questão.

A imagem de Capitu ia comigo, e a minha imaginação, assim como lhe atribuíra lágrimas, há pouco, assim lhe encheu a boca de riso agora: vi-a escrever no muro, falar-me, andar à volta, com os braços no ar; ouvi distintamente o meu nome, de uma doçura que me embriagou, e a voz era dela.

(Obra completa. Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 1992, p. 840)

Leia o trecho de Memórias de um sargento de milícias, de Manuel Antônio de Almeida, para responder à questão.

Era a comadre uma mulher baixa, excessivamente gorda, bonachona, ingênua ou tola até um certo ponto, e finória até outro; vivia do ofício de parteira, que adotara por curiosidade, e benzia de quebranto; todos a conheciam por muito beata e pela mais desabrida papa-missas da cidade. Era a folhinha mais exata de todas as festas religiosas que aqui se faziam; sabia de cor os dias em que se dizia missa em tal ou tal igreja, como a hora e até o nome do padre; era pontual à ladainha, ao terço, à novena, ao setenário; não lhe escapava via-sacra, procissão, nem sermão; trazia o tempo habilmente distribuído e as horas combinadas, de maneira que nunca lhe aconteceu chegar à igreja e achar já a missa no altar.

(Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira, 2016, p. 42)

Considere os trechos:

• ... vivia do ofício de parteira, que adotara por curiosidade...

• ... nunca lhe aconteceu chegar à igreja e achar já a missa no altar.

As expressões destacadas podem ser substituídas, preservando a correção conforme a norma-padrão da língua, respectivamente, por:

Leia o trecho de Memórias de um sargento de milícias, de Manuel Antônio de Almeida, para responder à questão.

Era a comadre uma mulher baixa, excessivamente gorda, bonachona, ingênua ou tola até um certo ponto, e finória até outro; vivia do ofício de parteira, que adotara por curiosidade, e benzia de quebranto; todos a conheciam por muito beata e pela mais desabrida papa-missas da cidade. Era a folhinha mais exata de todas as festas religiosas que aqui se faziam; sabia de cor os dias em que se dizia missa em tal ou tal igreja, como a hora e até o nome do padre; era pontual à ladainha, ao terço, à novena, ao setenário; não lhe escapava via-sacra, procissão, nem sermão; trazia o tempo habilmente distribuído e as horas combinadas, de maneira que nunca lhe aconteceu chegar à igreja e achar já a missa no altar.

(Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira, 2016, p. 42)