Questões Militares

Para aluno do ime

Foram encontradas 657 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Seja o polinômio p(x) = x3+ (ln a) x +eb, onde a e b são números reais positivos diferentes de zero. A soma dos cubos das raízes de p(x) depende

Obs.: e representa a base do logaritmo neperiano e ln a função logaritmo neperiano.

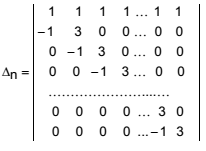

Considere o determinante de uma matriz de ordem n definido por:

Sabendo que ∆1 = 1, o valor de ∆10 é

Sejam r, s, t e v números inteiros positivos tais que r/s < t/v . Considere as seguintes relações:

O número total de relações que estão corretas é:

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

Billions of dollars spent on defeating improvised explosive devices (IED) are beginning to show what technology can and cannot do for the evolving struggle.

Two platoons of U.S. Army scouts are in a field deep in the notorious “Triangle of Death” south of Baghdad, a region of countless clashes between Sunni insurgents and Shia militias. The platoons are guided by a local man who’s warned them of pressure-plate improvised explosive devices, designed to explode when stepped on. He has assured them that he knows where the IED’s are, which means he is almost certainly a former Sunni insurgent.

The platoons come under harassing fire. It stops, but later the tension mounts again as they maneuver near an abandoned house known to shelter al-Qaeda fighters. A shot rings out; the scouts take cover. They don’t realize it’s just their local guide, with an itchy trigger finger, taking the potshot at the house. The lieutenant leading the patrol summons three riflemen to cover the abandoned house.

Then all hell breaks loose. One of the riflemen, a sergeant, steps on a pressure-plate IED. The blast badly injures him, the two other riflemen, and the lieutenant. A Navy explosives specialist along on the mission immediately springs into action, using classified gear to comb the area for more bombs. Until he gives the all clear, no one can move, not even to tend the bleeding men. Meanwhile, one of the frozen-inspace scouts notices another IED right next to him and gives a shout, provoking more combing in his area. Then a big area has to be cleared so that the medevac helicopter already on the way can land.

That incident, which took place on 7 November 2007, exhibits many of the hallmarks of the missions in Iraq and Afghanistan – a small patrol; a local man of dubious background; Navy specialists working with soldiers on dry land; and costly technologies pressed into service against cheap and crude weapons. And, most of all, death by IED.

The region described in the passage…