Questões Militares

Nível médio

Foram encontradas 45.670 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

II. A nitrificação é um processo de duas etapas no qual a amônia é convertida em nitrato por bactérias no solo: primeiro a amônia é oxidada a nitrito e, em seguida, o nitrito é oxidado a nitrato.

III. A desnitrificação é o processo pelo qual o nitrato é convertido novamente em nitrogênio atmosférico por bactérias desnitrificantes, processo que ocorre preferencialmente em condições de alto teor de oxigênio.

IV. As plantas contribuem para o ciclo do nitrogênio fixando o nitrogênio atmosférico por meio de relações simbióticas com bactérias fixadoras de nitrogênio.

V. O ciclo do nitrogênio consiste em várias etapas interconectadas, tais como: fixação, nitrificação, desnitrificação e amonificação.

Das afirmações acima, estão CORRETAS

II. Em uma mistura de octano e oxigênio, o combustível representa aproximadamente 78% da massa total.

III. A variação de temperatura da reação de combustível e oxigênio (por mol de combustível) é igual à variação de temperatura da reação de combustível e ar atmosférico (por mol de combustível).

IV. A entalpia molar de combustão de uma mistura de combustível e oxigênio é igual à entalpia molar de combustão de uma mistura de combustível e ar atmosférico. Assinale a opção que contém as afirmações CORRETAS.

Considere a elipse dada pela equação

⋋x2 + (⋋ + 4)y2 − 4⋋x − (10⋋ + 40)y + 25(⋋ + 4) − ⋋2 = 0,

e o círculo de equação

x2 + y2 − 4x − 12y + 36 = 0:

Estando o interior do círculo inteiramente contido no interior da elipse, o valor

de – ∈ R − {−4; 0} quando a excentricidade da elipse é máxima é igual a:

a0 + a1x + a2x2 + a3x3 + a4x4

A soma das raízes, contadas com multiplicidade, de todos os polinômios formados nesse processo é igual a:

A = {1; 2; 4; 8; 16; 32; 64; 128; 256}:

Qual o menor n ∈ N tal que todo subconjunto de A com n elementos contenha pelo menos um par cujo produto seja 256?

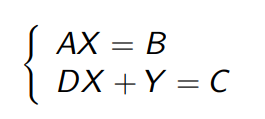

Sejam A; B; C; D ∈ Mn(R). Considere o sistema linear

nas variáveis X; Y ∈ Mn(R). Considere as afirmações:

I. Se det A = 0 ou det D = 0, então o sistema é impossível.

II. Se A = B, então o sistema possui uma única solução.

III. O sistema possui uma única solução apenas se A e D são inversíveis.

É (São) VERDADEIRA(S):

I. (A ∩ B) ∪ C = A ∩ (B ∪ C).

II. A ∩ B = C ∪ (B ∩ (R − C)).

III. A ∩ (B − C) = (A ∩ B) − C.

É (São) VERDADEIRA(S)