Questões de Concurso

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 9.532 questões

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the information provided by text, judge the items below.

According to the text above, judge the following items.

According to the text above, judge the following items.

According to the text above, judge the following items.

According to the text above, judge the following items.

Judge the following items according to the text above.

According to the text above, judge the following items.

Judge the following items according to the text above.

If It's for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man's

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

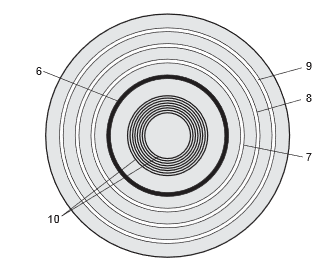

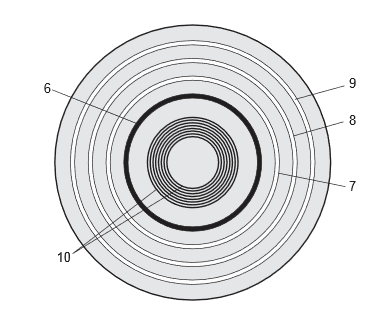

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I'm going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale," Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn't know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: 'Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.' "

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later," Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle."

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull's-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland's considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-josep...

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

De acordo com o texto,

If It’s for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man’s

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I’m going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale,” Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn’t know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: ‘Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.’ ”

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later,” Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle.”

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull’s-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland’s considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-joseph-woodland-inventor-of-the-bar-code-dies-at-91.html?nl=todaysheadlines

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

Dentro do contexto, a tradução correta para o significado de “it languished for years” é

If It's for Sale, His Lines Sort It

By MARGALIT FOX

It was born on a beach six decades ago, the product of a pressing need, an intellectual spark and the sweep of a young man's

fingers through the sand.

The result adorns almost every product of contemporary life, including groceries, wayward luggage and, if you are a

traditionalist, the newspaper you are holding.

The man on the beach that day was a mechanical-engineer-in-training named N. Joseph Woodland. With that transformative

stroke of his fingers − yielding a set of literal lines in the sand − Mr. Woodland, who died on Sunday at 91, conceived the modern bar

code.

Mr. Woodland was a graduate student when he and a classmate, Bernard Silver, created a technology, based on a printed

series of wide and narrow striations, that encoded consumer-product information for optical scanning.

Their idea, developed in the late 1940s and patented 60 years ago this fall, turned out to be ahead of its time, and the two men

together made only $15,000 from it, when they sold their patent to Philco. But the curious round symbol they devised would ultimately

give rise to the universal product code, or U.P.C., as the staggeringly prevalent rectangular bar code (it graces tens of millions of

different items) is officially known.

Here is part of the story behind the invention:

To represent information visually, he realized, he would need a code. The only code he knew was the one he had learned in the

Boy Scouts.

What would happen, Mr. Woodland wondered one day, if Morse code, with its elegant simplicity and limitless combinatorial

potential, were adapted graphically? He began trailing his fingers idly through the sand.

“What I'm going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale," Mr. Woodland told Smithsonian magazine in 1999. “I poked my four fingers

into the sand and for whatever reason − I didn't know − I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: 'Golly! Now I have four

lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.' "

That consequential pass was merely the beginning. “Only seconds later," Mr. Woodland continued, “I took my four fingers − they

were still in the sand − and I swept them around into a full circle."

Mr. Woodland favored the circular pattern for its omnidirectionality: a checkout clerk, he reasoned, could scan a product without

regard for its orientation.

But that method − a variegated bull's-eye of wide and narrow bands −, which depended on an immense scanner equipped with

a 500-watt light, was expensive and unwieldy, and it languished for years.

The two men eventually sold their patent to Philco for $15,000 − all they ever made from their invention.

By the time the patent expired at the end of the 1960s, Mr. Woodland was on the staff of I.B.M., where he worked from 1951

until his retirement in 1987.

Over time, laser scanning technology and the advent of the microprocessor made the bar code viable. In the early 1970s, an

I.B.M. colleague, George J. Laurer, designed the familiar black-and-white rectangle, based on the Woodland-Silver model and drawing

on Mr. Woodland's considerable input.

(Adapted from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/business/n-josep...

&emc=edit_th_20121214&_r=0)

Infere-se do texto que