Questões de Concurso Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 17.625 questões

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

An important strategy for understanding and interpreting meanings and intentions in texts is the knowledge of the reasons why the writer opted between active and passive constructions. In this respect, SWAN (2008:410) comments that: “In a passive clause, we usually use a phrase beginning with by if we want to mention the agent ‒ the person or thing that does the action, or that causes what happens. (Note, however, that agents are mentioned in only about 20 per cent of passive clauses.)”

In text II, the passive construction is employed several times, as in:

“[…] so that words are recognized automatically.” (§ 2)

“These word recognition strategies are taught as children […]” (§ 2)

“[…] a strategy between the two languages that has been demonstrated to be effective […]” (§ 4)

The explanation for the omission of the passive by‐agent in these sentences is found in:

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Decide whether the following statements are true or false, according to the text above and then choose the right alternative:

I. Comprehension of a text involves understanding of all its words.

II. Children learn how to read naturally, without the support of reading strategies instruction.

III. The development of the lexical system of the language and reading comprehension abilities takes place simultaneously.

IV. The knowledge of transparent words is not beneficial for learners of English as a SL or a FL.

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

TEXT 5:

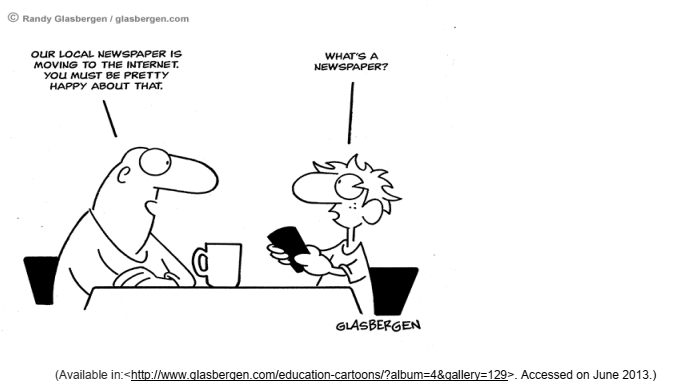

Indicate which excerpt taken from text 5 is illustrated by the following cartoon:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5:

TEXT 5: