Questões de Concurso Público SEFAZ-RJ 2014 para Auditor Fiscal da Receita Estadual - Prova 1

Foram encontradas 100 questões

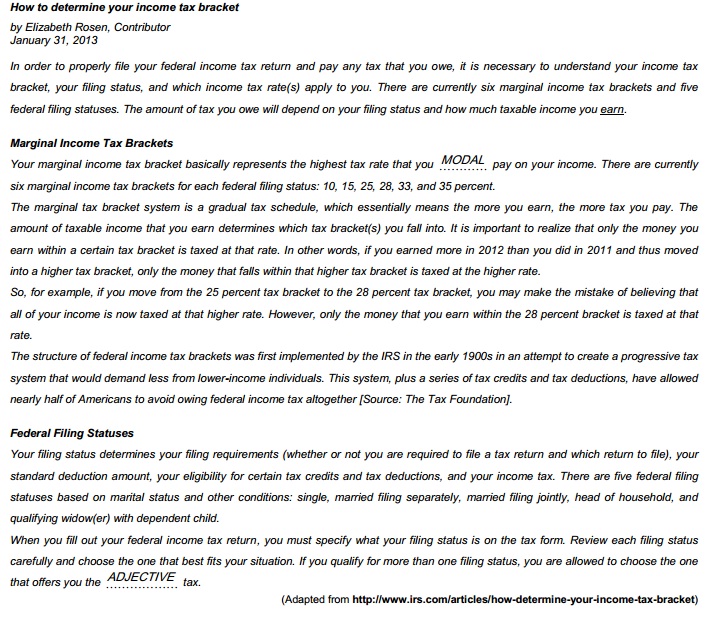

These are the tax rates for the 2012 tax year, if your filing status is “single”.

De acordo com o que é explicado no texto a respeito da tabela progressiva, o valor correto que preenche a célula (?) é

By Jonathan Mahler Sep 27, 2013

So Spain has decided to haul Lionel Messi into court for tax evasion, which strikes me as completely insane on pretty much every level.

You may remember the story from a few months back: The greatest soccer player in the world and his father were accused of setting up

a bunch of shell companies in Belize and Uruguay to avoid paying taxes on royalties and other licensing income.

Messi - who makes an estimated $41 million a year, about half from sponsors - reached a settlement with Spain’s tax authorities earlier

this summer, agreeing to pay the amount he apparently owed, plus interest. The matter was settled, or so it seemed. Messi could go

back to dazzling the world with his athleticism and creativity.

Only it turns out that Spain wasn’t quite done with Messi. His adopted country - Messi is Argentine but became a Spanish citizen in 2005

- is now considering pressing criminal charges against him.

Cracking down on tax-evading footballers has become something of a trend in Europe, where players and clubs have been known to

launder money through “image-rights companies” often set up in tax havens. When you need money - and Europe needs money - go to

the people who have it, or something like that. Over the summer, dozens of Italian soccer clubs were raided as part of an investigation

into a tax-fraud conspiracy. A number of English Premier League clubs were forced last year to pay millions of pounds in back taxes.

No one likes a tax cheat, and there’s little doubt that widespread tax fraud has helped eat away at the social safety net in Spain and

elsewhere, depriving schools, hospitals and other institutions of badly needed funds. But Europe is not going to find the answers to its

financial problems in the pockets of some professional soccer players and clubs.

Messi’s defense, delivered by his father, seems credible enough to me. “He is a footballer and that’s it,” Messi’s father Jorge said of his

soccer-prodigy son. “If there was an error, it was by our financial adviser. He created the company. My mistake was to have trusted the

adviser.” Even if Messi is legally responsible for the intricate tax dodge he is accused of having participated in, it’s pretty hard to believe

that he knew much about it.

More to the point, Lionel Messi is probably Spain’s most valuable global asset. What could possibly motivate the Spanish government to

want to tarnish his reputation, especially after he’s paid off his alleged debt? After four years of Great-Depression level unemployment,

have anxiety and despair curdled into vindictiveness?

Here’s another explanation: Maybe this whole case has less to do with money than it does with history. Maybe it’s no coincidence that

the target of the Spanish government’s weird wrath happens to play for FC Barcelona, which is, after all, "mes que un club." It's a symbol

of Catalan nationalism - and a bitter, longtime rival of Spain’s establishment team, Real Madrid.

Too conspiratorial? Prove it, Spain. Release Cristiano Ronaldo’s tax return.

(Adapted form http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-27/why-is-spain-really-taking-lionel-messi-to-tax-court-.html)

By Jonathan Mahler Sep 27, 2013

So Spain has decided to haul Lionel Messi into court for tax evasion, which strikes me as completely insane on pretty much every level.

You may remember the story from a few months back: The greatest soccer player in the world and his father were accused of setting up

a bunch of shell companies in Belize and Uruguay to avoid paying taxes on royalties and other licensing income.

Messi - who makes an estimated $41 million a year, about half from sponsors - reached a settlement with Spain’s tax authorities earlier

this summer, agreeing to pay the amount he apparently owed, plus interest. The matter was settled, or so it seemed. Messi could go

back to dazzling the world with his athleticism and creativity.

Only it turns out that Spain wasn’t quite done with Messi. His adopted country - Messi is Argentine but became a Spanish citizen in 2005

- is now considering pressing criminal charges against him.

Cracking down on tax-evading footballers has become something of a trend in Europe, where players and clubs have been known to

launder money through “image-rights companies” often set up in tax havens. When you need money - and Europe needs money - go to

the people who have it, or something like that. Over the summer, dozens of Italian soccer clubs were raided as part of an investigation

into a tax-fraud conspiracy. A number of English Premier League clubs were forced last year to pay millions of pounds in back taxes.

No one likes a tax cheat, and there’s little doubt that widespread tax fraud has helped eat away at the social safety net in Spain and

elsewhere, depriving schools, hospitals and other institutions of badly needed funds. But Europe is not going to find the answers to its

financial problems in the pockets of some professional soccer players and clubs.

Messi’s defense, delivered by his father, seems credible enough to me. “He is a footballer and that’s it,” Messi’s father Jorge said of his

soccer-prodigy son. “If there was an error, it was by our financial adviser. He created the company. My mistake was to have trusted the

adviser.” Even if Messi is legally responsible for the intricate tax dodge he is accused of having participated in, it’s pretty hard to believe

that he knew much about it.

More to the point, Lionel Messi is probably Spain’s most valuable global asset. What could possibly motivate the Spanish government to

want to tarnish his reputation, especially after he’s paid off his alleged debt? After four years of Great-Depression level unemployment,

have anxiety and despair curdled into vindictiveness?

Here’s another explanation: Maybe this whole case has less to do with money than it does with history. Maybe it’s no coincidence that

the target of the Spanish government’s weird wrath happens to play for FC Barcelona, which is, after all, "mes que un club." It's a symbol

of Catalan nationalism - and a bitter, longtime rival of Spain’s establishment team, Real Madrid.

Too conspiratorial? Prove it, Spain. Release Cristiano Ronaldo’s tax return.

(Adapted form http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-27/why-is-spain-really-taking-lionel-messi-to-tax-court-.html)

By Jonathan Mahler Sep 27, 2013

So Spain has decided to haul Lionel Messi into court for tax evasion, which strikes me as completely insane on pretty much every level.

You may remember the story from a few months back: The greatest soccer player in the world and his father were accused of setting up

a bunch of shell companies in Belize and Uruguay to avoid paying taxes on royalties and other licensing income.

Messi - who makes an estimated $41 million a year, about half from sponsors - reached a settlement with Spain’s tax authorities earlier

this summer, agreeing to pay the amount he apparently owed, plus interest. The matter was settled, or so it seemed. Messi could go

back to dazzling the world with his athleticism and creativity.

Only it turns out that Spain wasn’t quite done with Messi. His adopted country - Messi is Argentine but became a Spanish citizen in 2005

- is now considering pressing criminal charges against him.

Cracking down on tax-evading footballers has become something of a trend in Europe, where players and clubs have been known to

launder money through “image-rights companies” often set up in tax havens. When you need money - and Europe needs money - go to

the people who have it, or something like that. Over the summer, dozens of Italian soccer clubs were raided as part of an investigation

into a tax-fraud conspiracy. A number of English Premier League clubs were forced last year to pay millions of pounds in back taxes.

No one likes a tax cheat, and there’s little doubt that widespread tax fraud has helped eat away at the social safety net in Spain and

elsewhere, depriving schools, hospitals and other institutions of badly needed funds. But Europe is not going to find the answers to its

financial problems in the pockets of some professional soccer players and clubs.

Messi’s defense, delivered by his father, seems credible enough to me. “He is a footballer and that’s it,” Messi’s father Jorge said of his

soccer-prodigy son. “If there was an error, it was by our financial adviser. He created the company. My mistake was to have trusted the

adviser.” Even if Messi is legally responsible for the intricate tax dodge he is accused of having participated in, it’s pretty hard to believe

that he knew much about it.

More to the point, Lionel Messi is probably Spain’s most valuable global asset. What could possibly motivate the Spanish government to

want to tarnish his reputation, especially after he’s paid off his alleged debt? After four years of Great-Depression level unemployment,

have anxiety and despair curdled into vindictiveness?

Here’s another explanation: Maybe this whole case has less to do with money than it does with history. Maybe it’s no coincidence that

the target of the Spanish government’s weird wrath happens to play for FC Barcelona, which is, after all, "mes que un club." It's a symbol

of Catalan nationalism - and a bitter, longtime rival of Spain’s establishment team, Real Madrid.

Too conspiratorial? Prove it, Spain. Release Cristiano Ronaldo’s tax return.

(Adapted form http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-27/why-is-spain-really-taking-lionel-messi-to-tax-court-.html)

By Jonathan Mahler Sep 27, 2013

So Spain has decided to haul Lionel Messi into court for tax evasion, which strikes me as completely insane on pretty much every level.

You may remember the story from a few months back: The greatest soccer player in the world and his father were accused of setting up

a bunch of shell companies in Belize and Uruguay to avoid paying taxes on royalties and other licensing income.

Messi - who makes an estimated $41 million a year, about half from sponsors - reached a settlement with Spain’s tax authorities earlier

this summer, agreeing to pay the amount he apparently owed, plus interest. The matter was settled, or so it seemed. Messi could go

back to dazzling the world with his athleticism and creativity.

Only it turns out that Spain wasn’t quite done with Messi. His adopted country - Messi is Argentine but became a Spanish citizen in 2005

- is now considering pressing criminal charges against him.

Cracking down on tax-evading footballers has become something of a trend in Europe, where players and clubs have been known to

launder money through “image-rights companies” often set up in tax havens. When you need money - and Europe needs money - go to

the people who have it, or something like that. Over the summer, dozens of Italian soccer clubs were raided as part of an investigation

into a tax-fraud conspiracy. A number of English Premier League clubs were forced last year to pay millions of pounds in back taxes.

No one likes a tax cheat, and there’s little doubt that widespread tax fraud has helped eat away at the social safety net in Spain and

elsewhere, depriving schools, hospitals and other institutions of badly needed funds. But Europe is not going to find the answers to its

financial problems in the pockets of some professional soccer players and clubs.

Messi’s defense, delivered by his father, seems credible enough to me. “He is a footballer and that’s it,” Messi’s father Jorge said of his

soccer-prodigy son. “If there was an error, it was by our financial adviser. He created the company. My mistake was to have trusted the

adviser.” Even if Messi is legally responsible for the intricate tax dodge he is accused of having participated in, it’s pretty hard to believe

that he knew much about it.

More to the point, Lionel Messi is probably Spain’s most valuable global asset. What could possibly motivate the Spanish government to

want to tarnish his reputation, especially after he’s paid off his alleged debt? After four years of Great-Depression level unemployment,

have anxiety and despair curdled into vindictiveness?

Here’s another explanation: Maybe this whole case has less to do with money than it does with history. Maybe it’s no coincidence that

the target of the Spanish government’s weird wrath happens to play for FC Barcelona, which is, after all, "mes que un club." It's a symbol

of Catalan nationalism - and a bitter, longtime rival of Spain’s establishment team, Real Madrid.

Too conspiratorial? Prove it, Spain. Release Cristiano Ronaldo’s tax return.

(Adapted form http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-27/why-is-spain-really-taking-lionel-messi-to-tax-court-.html)

I. um conjunto de pessoas que trabalham na mesma unidade organizacional do organograma, fazendo cada uma sua parte para que o outro, ou outros, consolidem (por somatória) ou harmonizem o resultado final do trabalho.

II. um grupo de pessoas praticando atividades comuns, com objetivos idênticos, porém individualizados.

III. a obtenção de contribuições para otimizar os resultados comuns, sendo que todos são solidariamente responsáveis.

IV. um conjunto que gera sinergia positiva por meio de esforço coordenado e cujos esforços individuais resultam em um desempenho que é maior do que a soma dos seus insumos.

Está correto o que se afirma APENAS em

I. As fórmulas de ensino-aprendizagem oriundas do treinamento tradicional vêm se esgotando face aos múltiplos desafios que se apresentam no mercado de trabalho competitivo e globalizado.

II. O processo de transformação do conhecimento tácito em explícito não vem apresentando resultados satisfatórios, principalmente pelas organizações.

III. Empresas que adotam a learning organization não envolvem no seu ciclo de aprendizagem a cadeia de valor empresarial (acionistas, clientes, fornecedores, empregados, família e comunidade).

IV. Um fato relevante para a alavancagem da gestão do conhecimento, no Brasil, foi a extinção, em 1990, da Lei de Incentivo ao Treinamento e Desenvolvimento (Lei no 6.297/1975).

Está correto o que se afirma APENAS em

Índici "Y" = Nº de pessoas/ dias de trabalaho perdido por mês x 100

Nº médio de empregados x Nº de dias trabalhados

O índice “Y” é oficialmente denominado

Dentre as vantagens para a instituição, destaca-se o comprometimento dos funcionários, que é alcançado com uma gestão mais participativa. Sobre a Administração Participativa, considere:

I.É uma das ideias mais antigas da administração e tem suas raízes no Japão.

II. É considerada um dos novos paradigmas da administração, já que esse modelo de gestão integra as práticas mais avançadas nas relações de trabalho.

III.O diferencial desse modelo está em integrar os princípios de participação em um modelo estratégico de gestão articulado e considerado legítimo para toda a organização.

IV. Esse modelo exige flexibilidade da alta administração para permitir acesso às informações necessárias para que se possa tomar a decisão mais adequada possível.

Está correto o que se afirma APENAS em

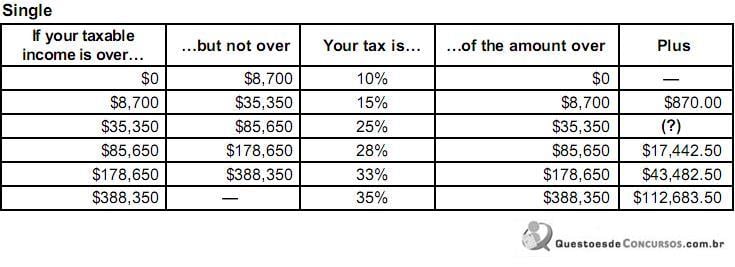

As despesas são ordinárias e as cotas trimestrais foram definidas em conformidade com a Lei no 4.320/1964. Foi permitido ao gestor da unidade orçamentária

I. Em 01/02/2012, o governo obteve uma operação de crédito por antecipação da receita orçamentária no valor de R$ 1.000.000,00. Em 30/06/2012, o governo liquidou esta operação de crédito, com o pagamento do principal mais juros, sendo estes últimos no valor de R$ 51.010,05.

II. Em 2012, o governo realizou despesa com o pagamento de parcela do principal, no valor de R$ 500.000,00, de uma operação de crédito de longo prazo obtida em 2010 e com juros e encargos referentes à mesma operação no valor de R$ 145.000,00.

As duas operações de crédito, em conjunto, geraram no exercício financeiro de 2012, em reais, uma despesa