Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para prefeitura de cuiabá - mt

Foram encontradas 2.451 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

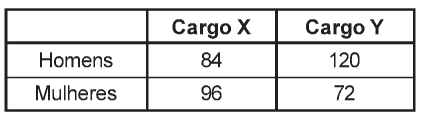

A tabela abaixo mostra o número de homens e mulheres inscritos em um concurso público em que são oferecidos apenas os cargos X e Y.

Considere a seguinte afirmação: “ Todo colecionador é excêntrico.”

A negação lógica dessa proposição equivale a:

Em um grupo com 42 pessoas em que todas falam Inglês ou Espanhol, sabe-se que:

• o número de pessoas que falam Inglês, mas não falam Espanhol, é igual ao dobro do número de pessoas que falam Inglês e Espanhol;

• o número de pessoas que falam Espanhol é igual ao dobro do número de pessoas que falam apenas Inglês.

O número de pessoas que falam somente um desses idiomas é:

O papel de intelectuais negros, como Machado de Assis, na Abolição

A historiadora Ana Flávia Magalhães Pinto fez deste tema sua tese de doutorado na Unicamp. Ela investigou a atuação de homens negros, livres, letrados e atuantes na imprensa e no cenário politico-cultural no eixo Rio-São Paulo, como Ferreira de Menezes, Luiz Gama, Machado de Assis, José do Patrocínio e Theophilo Dias de Castro. Segundo Ana Flávia, eles não só colaboraram para que o assunto ganhasse as páginas de jornais, como protagonizaram a criação de mecanismos e instrumentos de resistência, confronto e diálogo. Ela percebeu que não eram raros os momentos em que desenvolveram ações conjuntas.

- O acesso ao mundo das letras e da palavra impressa foi bastante aproveitado por esses “homens de cor”, que não apenas se valeram desses trânsitos em benefício próprio, mas também aproveitavam para levar adiante projetos coletivos voltados para a melhoria da qualidade de vida no país. Desse modo, aquilo que era construído no cotidiano, em conversas e reuniões, ganhava mais legitimidade ao chegar às páginas dos jornais - conta Ana Flávia.

A utilização da imprensa por eles foi de suma importância, na visão da pesquisadora. A “Gazeta da Tarde”, por exemplo, sob direção tanto de Ferreira de Menezes quanto de José Patrocínio, dedicou considerável espaço para tratar de casos de reescravização de libertos e escravização de gente livre, crime previsto no artigo 179 do Código Criminal do Império, como pontua a historiadora.

- Ao mesmo tempo, o jornal também se preocupou em dar visibilidade a trajetórias de sucesso de gente negra na liberdade, como aconteceu em 1883, quando a “Gazeta” publicou em folhetim uma versão da autobiografia do destacado abolicionista afro-americano Frederick Douglass - ilustra Ana Flávia.

Como observa o professor da UFF Humberto Machado, eles conheciam de perto as mazelas do cativeiro e levaram essa realidade às páginas dos jornais. José do Patrocínio, por exemplo, publicou livros que mostravam detalhes da escravidão como pano de fundo em formato de folhetim, que fizeram muito sucesso. Esses trabalhos penetravam em setores que desconheciam tal realidade.

- Até os analfabetos tomavam conhecimento, porque as pessoas se reuniam em quiosques no Centro do Rio de Janeiro e escutavam as notícias. A oralidade estava muito presente nesse processo. Fora isso, havia eventos, como conferências e apresentações teatrais, e as pessoas iam tomando conhecimento e se mobilizando contra a escravidão. O resultado foi um discurso voltado não só à população em geral, mas também aos senhores de engenho, mostrando a eles a inviabilidade da manutenção dos cativeiros - relata o professor, que escreveu o livro “Palavras e brados: José do Patrocínio e a imprensa abolicionista no Rio”.

(Adaptado de: https://extra.globo.com/noticias/saude-eciencia/especialistas-revelam-papel-de-intelectuais-negroscomo-machado-de-assis-na-abolicao-1810S16S.html)

O papel de intelectuais negros, como Machado de Assis, na Abolição

A historiadora Ana Flávia Magalhães Pinto fez deste tema sua tese de doutorado na Unicamp. Ela investigou a atuação de homens negros, livres, letrados e atuantes na imprensa e no cenário politico-cultural no eixo Rio-São Paulo, como Ferreira de Menezes, Luiz Gama, Machado de Assis, José do Patrocínio e Theophilo Dias de Castro. Segundo Ana Flávia, eles não só colaboraram para que o assunto ganhasse as páginas de jornais, como protagonizaram a criação de mecanismos e instrumentos de resistência, confronto e diálogo. Ela percebeu que não eram raros os momentos em que desenvolveram ações conjuntas.

- O acesso ao mundo das letras e da palavra impressa foi bastante aproveitado por esses “homens de cor”, que não apenas se valeram desses trânsitos em benefício próprio, mas também aproveitavam para levar adiante projetos coletivos voltados para a melhoria da qualidade de vida no país. Desse modo, aquilo que era construído no cotidiano, em conversas e reuniões, ganhava mais legitimidade ao chegar às páginas dos jornais - conta Ana Flávia.

A utilização da imprensa por eles foi de suma importância, na visão da pesquisadora. A “Gazeta da Tarde”, por exemplo, sob direção tanto de Ferreira de Menezes quanto de José Patrocínio, dedicou considerável espaço para tratar de casos de reescravização de libertos e escravização de gente livre, crime previsto no artigo 179 do Código Criminal do Império, como pontua a historiadora.

- Ao mesmo tempo, o jornal também se preocupou em dar visibilidade a trajetórias de sucesso de gente negra na liberdade, como aconteceu em 1883, quando a “Gazeta” publicou em folhetim uma versão da autobiografia do destacado abolicionista afro-americano Frederick Douglass - ilustra Ana Flávia.

Como observa o professor da UFF Humberto Machado, eles conheciam de perto as mazelas do cativeiro e levaram essa realidade às páginas dos jornais. José do Patrocínio, por exemplo, publicou livros que mostravam detalhes da escravidão como pano de fundo em formato de folhetim, que fizeram muito sucesso. Esses trabalhos penetravam em setores que desconheciam tal realidade.

- Até os analfabetos tomavam conhecimento, porque as pessoas se reuniam em quiosques no Centro do Rio de Janeiro e escutavam as notícias. A oralidade estava muito presente nesse processo. Fora isso, havia eventos, como conferências e apresentações teatrais, e as pessoas iam tomando conhecimento e se mobilizando contra a escravidão. O resultado foi um discurso voltado não só à população em geral, mas também aos senhores de engenho, mostrando a eles a inviabilidade da manutenção dos cativeiros - relata o professor, que escreveu o livro “Palavras e brados: José do Patrocínio e a imprensa abolicionista no Rio”.

(Adaptado de: https://extra.globo.com/noticias/saude-eciencia/especialistas-revelam-papel-de-intelectuais-negroscomo-machado-de-assis-na-abolicao-1810S16S.html)

O papel de intelectuais negros, como Machado de Assis, na Abolição

A historiadora Ana Flávia Magalhães Pinto fez deste tema sua tese de doutorado na Unicamp. Ela investigou a atuação de homens negros, livres, letrados e atuantes na imprensa e no cenário politico-cultural no eixo Rio-São Paulo, como Ferreira de Menezes, Luiz Gama, Machado de Assis, José do Patrocínio e Theophilo Dias de Castro. Segundo Ana Flávia, eles não só colaboraram para que o assunto ganhasse as páginas de jornais, como protagonizaram a criação de mecanismos e instrumentos de resistência, confronto e diálogo. Ela percebeu que não eram raros os momentos em que desenvolveram ações conjuntas.

- O acesso ao mundo das letras e da palavra impressa foi bastante aproveitado por esses “homens de cor”, que não apenas se valeram desses trânsitos em benefício próprio, mas também aproveitavam para levar adiante projetos coletivos voltados para a melhoria da qualidade de vida no país. Desse modo, aquilo que era construído no cotidiano, em conversas e reuniões, ganhava mais legitimidade ao chegar às páginas dos jornais - conta Ana Flávia.

A utilização da imprensa por eles foi de suma importância, na visão da pesquisadora. A “Gazeta da Tarde”, por exemplo, sob direção tanto de Ferreira de Menezes quanto de José Patrocínio, dedicou considerável espaço para tratar de casos de reescravização de libertos e escravização de gente livre, crime previsto no artigo 179 do Código Criminal do Império, como pontua a historiadora.

- Ao mesmo tempo, o jornal também se preocupou em dar visibilidade a trajetórias de sucesso de gente negra na liberdade, como aconteceu em 1883, quando a “Gazeta” publicou em folhetim uma versão da autobiografia do destacado abolicionista afro-americano Frederick Douglass - ilustra Ana Flávia.

Como observa o professor da UFF Humberto Machado, eles conheciam de perto as mazelas do cativeiro e levaram essa realidade às páginas dos jornais. José do Patrocínio, por exemplo, publicou livros que mostravam detalhes da escravidão como pano de fundo em formato de folhetim, que fizeram muito sucesso. Esses trabalhos penetravam em setores que desconheciam tal realidade.

- Até os analfabetos tomavam conhecimento, porque as pessoas se reuniam em quiosques no Centro do Rio de Janeiro e escutavam as notícias. A oralidade estava muito presente nesse processo. Fora isso, havia eventos, como conferências e apresentações teatrais, e as pessoas iam tomando conhecimento e se mobilizando contra a escravidão. O resultado foi um discurso voltado não só à população em geral, mas também aos senhores de engenho, mostrando a eles a inviabilidade da manutenção dos cativeiros - relata o professor, que escreveu o livro “Palavras e brados: José do Patrocínio e a imprensa abolicionista no Rio”.

(Adaptado de: https://extra.globo.com/noticias/saude-eciencia/especialistas-revelam-papel-de-intelectuais-negroscomo-machado-de-assis-na-abolicao-1810S16S.html)

O papel de intelectuais negros, como Machado de Assis, na Abolição

A historiadora Ana Flávia Magalhães Pinto fez deste tema sua tese de doutorado na Unicamp. Ela investigou a atuação de homens negros, livres, letrados e atuantes na imprensa e no cenário politico-cultural no eixo Rio-São Paulo, como Ferreira de Menezes, Luiz Gama, Machado de Assis, José do Patrocínio e Theophilo Dias de Castro. Segundo Ana Flávia, eles não só colaboraram para que o assunto ganhasse as páginas de jornais, como protagonizaram a criação de mecanismos e instrumentos de resistência, confronto e diálogo. Ela percebeu que não eram raros os momentos em que desenvolveram ações conjuntas.

- O acesso ao mundo das letras e da palavra impressa foi bastante aproveitado por esses “homens de cor”, que não apenas se valeram desses trânsitos em benefício próprio, mas também aproveitavam para levar adiante projetos coletivos voltados para a melhoria da qualidade de vida no país. Desse modo, aquilo que era construído no cotidiano, em conversas e reuniões, ganhava mais legitimidade ao chegar às páginas dos jornais - conta Ana Flávia.

A utilização da imprensa por eles foi de suma importância, na visão da pesquisadora. A “Gazeta da Tarde”, por exemplo, sob direção tanto de Ferreira de Menezes quanto de José Patrocínio, dedicou considerável espaço para tratar de casos de reescravização de libertos e escravização de gente livre, crime previsto no artigo 179 do Código Criminal do Império, como pontua a historiadora.

- Ao mesmo tempo, o jornal também se preocupou em dar visibilidade a trajetórias de sucesso de gente negra na liberdade, como aconteceu em 1883, quando a “Gazeta” publicou em folhetim uma versão da autobiografia do destacado abolicionista afro-americano Frederick Douglass - ilustra Ana Flávia.

Como observa o professor da UFF Humberto Machado, eles conheciam de perto as mazelas do cativeiro e levaram essa realidade às páginas dos jornais. José do Patrocínio, por exemplo, publicou livros que mostravam detalhes da escravidão como pano de fundo em formato de folhetim, que fizeram muito sucesso. Esses trabalhos penetravam em setores que desconheciam tal realidade.

- Até os analfabetos tomavam conhecimento, porque as pessoas se reuniam em quiosques no Centro do Rio de Janeiro e escutavam as notícias. A oralidade estava muito presente nesse processo. Fora isso, havia eventos, como conferências e apresentações teatrais, e as pessoas iam tomando conhecimento e se mobilizando contra a escravidão. O resultado foi um discurso voltado não só à população em geral, mas também aos senhores de engenho, mostrando a eles a inviabilidade da manutenção dos cativeiros - relata o professor, que escreveu o livro “Palavras e brados: José do Patrocínio e a imprensa abolicionista no Rio”.

(Adaptado de: https://extra.globo.com/noticias/saude-eciencia/especialistas-revelam-papel-de-intelectuais-negroscomo-machado-de-assis-na-abolicao-1810S16S.html)

TEXTO II

It has become more or less a cliché these days to refer to English as a world language. At the 1984 conference to celebrate the SOth anniversary of the British Council there was a debate between Sir Randolph Quirk and Professor Braj Kachru on the (literally) million dollar question of 'who owns English’, and hence whose English must be adopted as the model for teaching the language worldwide (Quirk and Widdowson 198S). Since then, much has been written on the role of English as a language of international communication, and the desirability or otherwise of adopting one of the Inner Circle varieties of English (to all intents and purposes, either British or American) as the canonical model for teaching it as a second or foreign language. The position vigorously defended by Quirk in that debate— succinctly captured in the phrase 'a single monochrome standard’ (Quirk 198S: 6)— no longer appeals to the majority of those who are involved in the ELT enterprise in one way or another. Instead, Kachru’s equally spirited insistence that 'the native speakers [of English] seem to have lost the exclusive prerogative to control its standardisation’ (Kachru 198S: 3O), and his plea for a paradigm shift in linguistic and pedagogical research so as to bring it more in tune with the changing landscape, have continued to strike a favourable chord with most ELT professionals. And the idea that English belongs to everyone who speaks it has been steadily gaining ground.

Though still resisted in some quarters, the very idea of World English (henceforward, W E) makes the whole question of the 'ownership’ of English problematic, not to say completely anachronistic. Widdowson expressed the idea in a very telling manner when he wrote 'It is a matter of considerable pride and satisfaction for native speakers of English that their language is an international means of communication. But the point is that it is only international to the extent that it is not their language.’ (italics mine) (Widdowson 1994: 38S).

(...)

Lest I should be misunderstood here, please note what it is that I am not claiming. I am not saying that there are no native speakers of English any more— if by native speakers we mean persons who were born and brought up in monolingual households with no contact with other languages. Indeed, that would be an absurd thing to say. As with every other language, there will— for the immediately foreseeable future at least— continue to be children born into monolingual English-speaking households who will, under the familiar criteria established for the purpose (Davies 1991), qualify as native speakers of English. But what we are interested in at the moment is W E, not the English language as it is spoken in Englishspeaking households, or the Houses of Parliament in Britain. W E is a language (for want of a better term, that is) spoken across the world— routinely at the check-in desks and in the corridors and departure lounges of some of the world’s busiest airports, typically during multinational business encounters, periodically during the Olympics or World Cup Football seasons, international trade fairs, academic conferences, and so on [...].

RAJAGOPALAN, K. The concept of ‘World English’ and its

implications for ELT. ELT Journal Volume S8I2 April 2004.

TEXTO II

It has become more or less a cliché these days to refer to English as a world language. At the 1984 conference to celebrate the SOth anniversary of the British Council there was a debate between Sir Randolph Quirk and Professor Braj Kachru on the (literally) million dollar question of 'who owns English’, and hence whose English must be adopted as the model for teaching the language worldwide (Quirk and Widdowson 198S). Since then, much has been written on the role of English as a language of international communication, and the desirability or otherwise of adopting one of the Inner Circle varieties of English (to all intents and purposes, either British or American) as the canonical model for teaching it as a second or foreign language. The position vigorously defended by Quirk in that debate— succinctly captured in the phrase 'a single monochrome standard’ (Quirk 198S: 6)— no longer appeals to the majority of those who are involved in the ELT enterprise in one way or another. Instead, Kachru’s equally spirited insistence that 'the native speakers [of English] seem to have lost the exclusive prerogative to control its standardisation’ (Kachru 198S: 3O), and his plea for a paradigm shift in linguistic and pedagogical research so as to bring it more in tune with the changing landscape, have continued to strike a favourable chord with most ELT professionals. And the idea that English belongs to everyone who speaks it has been steadily gaining ground.

Though still resisted in some quarters, the very idea of World English (henceforward, W E) makes the whole question of the 'ownership’ of English problematic, not to say completely anachronistic. Widdowson expressed the idea in a very telling manner when he wrote 'It is a matter of considerable pride and satisfaction for native speakers of English that their language is an international means of communication. But the point is that it is only international to the extent that it is not their language.’ (italics mine) (Widdowson 1994: 38S).

(...)

Lest I should be misunderstood here, please note what it is that I am not claiming. I am not saying that there are no native speakers of English any more— if by native speakers we mean persons who were born and brought up in monolingual households with no contact with other languages. Indeed, that would be an absurd thing to say. As with every other language, there will— for the immediately foreseeable future at least— continue to be children born into monolingual English-speaking households who will, under the familiar criteria established for the purpose (Davies 1991), qualify as native speakers of English. But what we are interested in at the moment is W E, not the English language as it is spoken in Englishspeaking households, or the Houses of Parliament in Britain. W E is a language (for want of a better term, that is) spoken across the world— routinely at the check-in desks and in the corridors and departure lounges of some of the world’s busiest airports, typically during multinational business encounters, periodically during the Olympics or World Cup Football seasons, international trade fairs, academic conferences, and so on [...].

RAJAGOPALAN, K. The concept of ‘World English’ and its

implications for ELT. ELT Journal Volume S8I2 April 2004.

TEXTO II

It has become more or less a cliché these days to refer to English as a world language. At the 1984 conference to celebrate the SOth anniversary of the British Council there was a debate between Sir Randolph Quirk and Professor Braj Kachru on the (literally) million dollar question of 'who owns English’, and hence whose English must be adopted as the model for teaching the language worldwide (Quirk and Widdowson 198S). Since then, much has been written on the role of English as a language of international communication, and the desirability or otherwise of adopting one of the Inner Circle varieties of English (to all intents and purposes, either British or American) as the canonical model for teaching it as a second or foreign language. The position vigorously defended by Quirk in that debate— succinctly captured in the phrase 'a single monochrome standard’ (Quirk 198S: 6)— no longer appeals to the majority of those who are involved in the ELT enterprise in one way or another. Instead, Kachru’s equally spirited insistence that 'the native speakers [of English] seem to have lost the exclusive prerogative to control its standardisation’ (Kachru 198S: 3O), and his plea for a paradigm shift in linguistic and pedagogical research so as to bring it more in tune with the changing landscape, have continued to strike a favourable chord with most ELT professionals. And the idea that English belongs to everyone who speaks it has been steadily gaining ground.

Though still resisted in some quarters, the very idea of World English (henceforward, W E) makes the whole question of the 'ownership’ of English problematic, not to say completely anachronistic. Widdowson expressed the idea in a very telling manner when he wrote 'It is a matter of considerable pride and satisfaction for native speakers of English that their language is an international means of communication. But the point is that it is only international to the extent that it is not their language.’ (italics mine) (Widdowson 1994: 38S).

(...)

Lest I should be misunderstood here, please note what it is that I am not claiming. I am not saying that there are no native speakers of English any more— if by native speakers we mean persons who were born and brought up in monolingual households with no contact with other languages. Indeed, that would be an absurd thing to say. As with every other language, there will— for the immediately foreseeable future at least— continue to be children born into monolingual English-speaking households who will, under the familiar criteria established for the purpose (Davies 1991), qualify as native speakers of English. But what we are interested in at the moment is W E, not the English language as it is spoken in Englishspeaking households, or the Houses of Parliament in Britain. W E is a language (for want of a better term, that is) spoken across the world— routinely at the check-in desks and in the corridors and departure lounges of some of the world’s busiest airports, typically during multinational business encounters, periodically during the Olympics or World Cup Football seasons, international trade fairs, academic conferences, and so on [...].

RAJAGOPALAN, K. The concept of ‘World English’ and its

implications for ELT. ELT Journal Volume S8I2 April 2004.

TEXTO II

It has become more or less a cliché these days to refer to English as a world language. At the 1984 conference to celebrate the SOth anniversary of the British Council there was a debate between Sir Randolph Quirk and Professor Braj Kachru on the (literally) million dollar question of 'who owns English’, and hence whose English must be adopted as the model for teaching the language worldwide (Quirk and Widdowson 198S). Since then, much has been written on the role of English as a language of international communication, and the desirability or otherwise of adopting one of the Inner Circle varieties of English (to all intents and purposes, either British or American) as the canonical model for teaching it as a second or foreign language. The position vigorously defended by Quirk in that debate— succinctly captured in the phrase 'a single monochrome standard’ (Quirk 198S: 6)— no longer appeals to the majority of those who are involved in the ELT enterprise in one way or another. Instead, Kachru’s equally spirited insistence that 'the native speakers [of English] seem to have lost the exclusive prerogative to control its standardisation’ (Kachru 198S: 3O), and his plea for a paradigm shift in linguistic and pedagogical research so as to bring it more in tune with the changing landscape, have continued to strike a favourable chord with most ELT professionals. And the idea that English belongs to everyone who speaks it has been steadily gaining ground.

Though still resisted in some quarters, the very idea of World English (henceforward, W E) makes the whole question of the 'ownership’ of English problematic, not to say completely anachronistic. Widdowson expressed the idea in a very telling manner when he wrote 'It is a matter of considerable pride and satisfaction for native speakers of English that their language is an international means of communication. But the point is that it is only international to the extent that it is not their language.’ (italics mine) (Widdowson 1994: 38S).

(...)

Lest I should be misunderstood here, please note what it is that I am not claiming. I am not saying that there are no native speakers of English any more— if by native speakers we mean persons who were born and brought up in monolingual households with no contact with other languages. Indeed, that would be an absurd thing to say. As with every other language, there will— for the immediately foreseeable future at least— continue to be children born into monolingual English-speaking households who will, under the familiar criteria established for the purpose (Davies 1991), qualify as native speakers of English. But what we are interested in at the moment is W E, not the English language as it is spoken in Englishspeaking households, or the Houses of Parliament in Britain. W E is a language (for want of a better term, that is) spoken across the world— routinely at the check-in desks and in the corridors and departure lounges of some of the world’s busiest airports, typically during multinational business encounters, periodically during the Olympics or World Cup Football seasons, international trade fairs, academic conferences, and so on [...].

RAJAGOPALAN, K. The concept of ‘World English’ and its

implications for ELT. ELT Journal Volume S8I2 April 2004.

TEXTO I

The English for Specific Purpose Myths in Brazil

The most prevailing myth associated to ESP in Brazil, and created because of the Brazilian ESP Project, is that “ESP is reading”. [...] Reading was the only skill that deserved special attention in the Project. Thus, on one hand, ESP is to be understood as synonymous with reading and, on the other hand, any reading course is to be understood as ESP. As a consequence of this current myth another one comes together: “ESP is monoskill” as any teaching action that is related to its design and implementation is devoted exclusively to one ability. However, the point to stress here is that this myth may be deconstructed easily when the reasons why the Brazilian Project concentrated on reading are made apparent: this was the paramount ability identified during the needs analysis conducted in the late I9 70 's as needed by most target groups. [...] These should be recognizable arguments for teaching reading comprehension and, thus, making of this course a truly ESP course. Unfortunately, there are still many professionals in Brazil who still think that if you need to teach any other skill or more than one skill you are not teaching ESP.

Another recurrent myth is: “ESP is technical English”. One of the reasons that may explain such a misconception may have stemmed from the I970's and early 1980's when many materials on the market focusing on the language of sciences, a well-established idea among ESP practitioners in many parts of the world, were produced. [...] In addition to that, many efforts were made to characterize the language of science, and for a long time, this was broken down into domains: the language of chemistry, the language of medicine, etc. [...] Turning back to the argument, such domain-specific breakdown materials may have contributed to an understanding that these specific Englishes were sufficiently different for a course to be based on them, with specific vocabulary being one of the chief features, and consequently creating such a misconception. Another explanation but this time rooted in “local” reasons may be found in the fact that subject matters of students' disciplines were (and still are in some places) brought to compose part of the syllabuses of many ESP courses. Third, the fact that the Technical Schools, now upgraded as Technological Centres for Higher Education (CEFETs), joined the Brazilian ESP Project in the mid-eighties may have strongly contributed to this association.

Other current myths aligned with ESP Reading Courses due to the adopted methodology and the specific contents that were developed during the implementation of the ESP Project in the country are: “the use of the dictionary is not allowed”, “grammar is not taught”, and “Portuguese has to be used in the classroom”. In order to better understand these misconceptions it is necessary to briefly explain the underlying principles adopted to teach reading. Some of the procedures put into work in the classroom were based on the belief that cognitive and linguistic difficulties should be eased and/or balanced during the learning process by making up the most of students' previous knowledge. So, the use of the dictionary during the initial classes was avoided to make students explore other areas of knowledge and resources rather than those, which were believed to be very familiar (the dictionary, translation of word by word, for example). The same applies to the teaching of grammar: strategies were emphasized over grammar at the beginning of the course and the teaching of grammar, in turn, concentrated on discourse grammar rather than traditional (structural) teaching of grammar. The same underlying principle was attributed to the use of Portuguese by teacher and students in the classroom, as well as in the written instructions of activities [...].

RAMOS, R. C.G ESP in Brazil: history, new trends and challenges. In: KRZANOWSKI, M. (Ed.). English for academic and specific purposes in developing, emerging and least developed countries. IATEFL, 2008. p. 68-83.

TEXTO I

The English for Specific Purpose Myths in Brazil

The most prevailing myth associated to ESP in Brazil, and created because of the Brazilian ESP Project, is that “ESP is reading”. [...] Reading was the only skill that deserved special attention in the Project. Thus, on one hand, ESP is to be understood as synonymous with reading and, on the other hand, any reading course is to be understood as ESP. As a consequence of this current myth another one comes together: “ESP is monoskill” as any teaching action that is related to its design and implementation is devoted exclusively to one ability. However, the point to stress here is that this myth may be deconstructed easily when the reasons why the Brazilian Project concentrated on reading are made apparent: this was the paramount ability identified during the needs analysis conducted in the late I9 70 's as needed by most target groups. [...] These should be recognizable arguments for teaching reading comprehension and, thus, making of this course a truly ESP course. Unfortunately, there are still many professionals in Brazil who still think that if you need to teach any other skill or more than one skill you are not teaching ESP.

Another recurrent myth is: “ESP is technical English”. One of the reasons that may explain such a misconception may have stemmed from the I970's and early 1980's when many materials on the market focusing on the language of sciences, a well-established idea among ESP practitioners in many parts of the world, were produced. [...] In addition to that, many efforts were made to characterize the language of science, and for a long time, this was broken down into domains: the language of chemistry, the language of medicine, etc. [...] Turning back to the argument, such domain-specific breakdown materials may have contributed to an understanding that these specific Englishes were sufficiently different for a course to be based on them, with specific vocabulary being one of the chief features, and consequently creating such a misconception. Another explanation but this time rooted in “local” reasons may be found in the fact that subject matters of students' disciplines were (and still are in some places) brought to compose part of the syllabuses of many ESP courses. Third, the fact that the Technical Schools, now upgraded as Technological Centres for Higher Education (CEFETs), joined the Brazilian ESP Project in the mid-eighties may have strongly contributed to this association.

Other current myths aligned with ESP Reading Courses due to the adopted methodology and the specific contents that were developed during the implementation of the ESP Project in the country are: “the use of the dictionary is not allowed”, “grammar is not taught”, and “Portuguese has to be used in the classroom”. In order to better understand these misconceptions it is necessary to briefly explain the underlying principles adopted to teach reading. Some of the procedures put into work in the classroom were based on the belief that cognitive and linguistic difficulties should be eased and/or balanced during the learning process by making up the most of students' previous knowledge. So, the use of the dictionary during the initial classes was avoided to make students explore other areas of knowledge and resources rather than those, which were believed to be very familiar (the dictionary, translation of word by word, for example). The same applies to the teaching of grammar: strategies were emphasized over grammar at the beginning of the course and the teaching of grammar, in turn, concentrated on discourse grammar rather than traditional (structural) teaching of grammar. The same underlying principle was attributed to the use of Portuguese by teacher and students in the classroom, as well as in the written instructions of activities [...].

RAMOS, R. C.G ESP in Brazil: history, new trends and challenges. In: KRZANOWSKI, M. (Ed.). English for academic and specific purposes in developing, emerging and least developed countries. IATEFL, 2008. p. 68-83.