Questões de Concurso

Para prefeitura de leopoldina - mg

Foram encontradas 381 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Refugee judokas searching for peace while fighting for their Olympic dream in Rio

More than two and a half years after they came to Rio de Janeiro to compete in the World Judo Championships, two refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo are still here, in pursuit of an extraordinary Olympic dream. When teams from more than 200 countries march into the Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony of the Rio 2016 Games on 5 August, Popole Misenga and Yolanda Mabika intend to be among them, walking behind the Olympic flag. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) will mount a unique team of refugee athletes which will compete in Rio. It has been a long journey from central Africa and from a war that has claimed an estimated 5.4 million lives. Mabika, now 28, cannot hold back the tears when she remembers the brothers and sisters she has not seen since 1998, when she was evacuated from her home town to the country’s capital, Kinshasa. It was there, as a child, that she first took up judo. Misenga’s mother was murdered when he was just six years old. The young child wandered for days in the Congolese rainforest before he too was rescued and taken to Kinshasa. Like his compatriot, he soon took to judo, a sport which the Congolese government saw as an ideal way of giving some structure to the lives of the country’s countless orphans. In 2010, Misenga won a bronze medal at the under-20 African Judo Championship. But Misenga and Mabika said training conditions were excessively rigorous, with losing judokas beaten and locked in cells. At the 2013 World Judo Championship, Misenga took the opportunity to begin a better life. After escaping from the team hotel, a couple of days later Misenga found himself in the favela community of Cinco Bocas in northern Rio, home to most of the city’s Congolese community of some 900 people. He sent Mabika a message and she also decided to stay. Life in northern Rio has not always been easy for the judokas. It has been a story of odd jobs and informal employment.The two athletes are now training three times a week at the Instituto Reação. The learning curve has been steep. Geraldo Bernardes, the veteran coach of the Brazilian team in four Olympic Games, says that Misenga and Mabika were initially far too aggressive in training. “They were used to being punished and mistreated when they lost,” Geraldo explains. “I had to tell them that training and fighting are different things.”

Misenga told rio2016.com that he had adjusted to his new surrounds: “I have learnt a lot on the technical side. I can feel in my body that I have learnt what was missing before in my judo.” Their coach says the two judokas are rough diamonds and are still making up for the lost time in their training. Brazil has a strong tradition in the sport and both athletes are hoping that by refining their skills in the country they will make the cut when the IOC decides which athletes (from a shortlist of 43) will form part of Team Refugee in June. In the meantime, both Misenga and Mabika are enjoying their new lives in Rio. The Instituto Reação and the local Estácio de Sá university have given them the opportunity to learn Portuguese, maths and other subjects. Neither of the two judokas has any plan to leave the new home town that has given them so much.

(Available in: http://www.rio2016.com. Adapted.)

Refugee judokas searching for peace while fighting for their Olympic dream in Rio

More than two and a half years after they came to Rio de Janeiro to compete in the World Judo Championships, two refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo are still here, in pursuit of an extraordinary Olympic dream. When teams from more than 200 countries march into the Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony of the Rio 2016 Games on 5 August, Popole Misenga and Yolanda Mabika intend to be among them, walking behind the Olympic flag. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) will mount a unique team of refugee athletes which will compete in Rio. It has been a long journey from central Africa and from a war that has claimed an estimated 5.4 million lives. Mabika, now 28, cannot hold back the tears when she remembers the brothers and sisters she has not seen since 1998, when she was evacuated from her home town to the country’s capital, Kinshasa. It was there, as a child, that she first took up judo. Misenga’s mother was murdered when he was just six years old. The young child wandered for days in the Congolese rainforest before he too was rescued and taken to Kinshasa. Like his compatriot, he soon took to judo, a sport which the Congolese government saw as an ideal way of giving some structure to the lives of the country’s countless orphans. In 2010, Misenga won a bronze medal at the under-20 African Judo Championship. But Misenga and Mabika said training conditions were excessively rigorous, with losing judokas beaten and locked in cells. At the 2013 World Judo Championship, Misenga took the opportunity to begin a better life. After escaping from the team hotel, a couple of days later Misenga found himself in the favela community of Cinco Bocas in northern Rio, home to most of the city’s Congolese community of some 900 people. He sent Mabika a message and she also decided to stay. Life in northern Rio has not always been easy for the judokas. It has been a story of odd jobs and informal employment.The two athletes are now training three times a week at the Instituto Reação. The learning curve has been steep. Geraldo Bernardes, the veteran coach of the Brazilian team in four Olympic Games, says that Misenga and Mabika were initially far too aggressive in training. “They were used to being punished and mistreated when they lost,” Geraldo explains. “I had to tell them that training and fighting are different things.”

Misenga told rio2016.com that he had adjusted to his new surrounds: “I have learnt a lot on the technical side. I can feel in my body that I have learnt what was missing before in my judo.” Their coach says the two judokas are rough diamonds and are still making up for the lost time in their training. Brazil has a strong tradition in the sport and both athletes are hoping that by refining their skills in the country they will make the cut when the IOC decides which athletes (from a shortlist of 43) will form part of Team Refugee in June. In the meantime, both Misenga and Mabika are enjoying their new lives in Rio. The Instituto Reação and the local Estácio de Sá university have given them the opportunity to learn Portuguese, maths and other subjects. Neither of the two judokas has any plan to leave the new home town that has given them so much.

(Available in: http://www.rio2016.com. Adapted.)

Refugee judokas searching for peace while fighting for their Olympic dream in Rio

More than two and a half years after they came to Rio de Janeiro to compete in the World Judo Championships, two refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo are still here, in pursuit of an extraordinary Olympic dream. When teams from more than 200 countries march into the Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony of the Rio 2016 Games on 5 August, Popole Misenga and Yolanda Mabika intend to be among them, walking behind the Olympic flag. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) will mount a unique team of refugee athletes which will compete in Rio. It has been a long journey from central Africa and from a war that has claimed an estimated 5.4 million lives. Mabika, now 28, cannot hold back the tears when she remembers the brothers and sisters she has not seen since 1998, when she was evacuated from her home town to the country’s capital, Kinshasa. It was there, as a child, that she first took up judo. Misenga’s mother was murdered when he was just six years old. The young child wandered for days in the Congolese rainforest before he too was rescued and taken to Kinshasa. Like his compatriot, he soon took to judo, a sport which the Congolese government saw as an ideal way of giving some structure to the lives of the country’s countless orphans. In 2010, Misenga won a bronze medal at the under-20 African Judo Championship. But Misenga and Mabika said training conditions were excessively rigorous, with losing judokas beaten and locked in cells. At the 2013 World Judo Championship, Misenga took the opportunity to begin a better life. After escaping from the team hotel, a couple of days later Misenga found himself in the favela community of Cinco Bocas in northern Rio, home to most of the city’s Congolese community of some 900 people. He sent Mabika a message and she also decided to stay. Life in northern Rio has not always been easy for the judokas. It has been a story of odd jobs and informal employment.The two athletes are now training three times a week at the Instituto Reação. The learning curve has been steep. Geraldo Bernardes, the veteran coach of the Brazilian team in four Olympic Games, says that Misenga and Mabika were initially far too aggressive in training. “They were used to being punished and mistreated when they lost,” Geraldo explains. “I had to tell them that training and fighting are different things.”

Misenga told rio2016.com that he had adjusted to his new surrounds: “I have learnt a lot on the technical side. I can feel in my body that I have learnt what was missing before in my judo.” Their coach says the two judokas are rough diamonds and are still making up for the lost time in their training. Brazil has a strong tradition in the sport and both athletes are hoping that by refining their skills in the country they will make the cut when the IOC decides which athletes (from a shortlist of 43) will form part of Team Refugee in June. In the meantime, both Misenga and Mabika are enjoying their new lives in Rio. The Instituto Reação and the local Estácio de Sá university have given them the opportunity to learn Portuguese, maths and other subjects. Neither of the two judokas has any plan to leave the new home town that has given them so much.

(Available in: http://www.rio2016.com. Adapted.)

Refugee judokas searching for peace while fighting for their Olympic dream in Rio

More than two and a half years after they came to Rio de Janeiro to compete in the World Judo Championships, two refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo are still here, in pursuit of an extraordinary Olympic dream. When teams from more than 200 countries march into the Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony of the Rio 2016 Games on 5 August, Popole Misenga and Yolanda Mabika intend to be among them, walking behind the Olympic flag. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) will mount a unique team of refugee athletes which will compete in Rio. It has been a long journey from central Africa and from a war that has claimed an estimated 5.4 million lives. Mabika, now 28, cannot hold back the tears when she remembers the brothers and sisters she has not seen since 1998, when she was evacuated from her home town to the country’s capital, Kinshasa. It was there, as a child, that she first took up judo. Misenga’s mother was murdered when he was just six years old. The young child wandered for days in the Congolese rainforest before he too was rescued and taken to Kinshasa. Like his compatriot, he soon took to judo, a sport which the Congolese government saw as an ideal way of giving some structure to the lives of the country’s countless orphans. In 2010, Misenga won a bronze medal at the under-20 African Judo Championship. But Misenga and Mabika said training conditions were excessively rigorous, with losing judokas beaten and locked in cells. At the 2013 World Judo Championship, Misenga took the opportunity to begin a better life. After escaping from the team hotel, a couple of days later Misenga found himself in the favela community of Cinco Bocas in northern Rio, home to most of the city’s Congolese community of some 900 people. He sent Mabika a message and she also decided to stay. Life in northern Rio has not always been easy for the judokas. It has been a story of odd jobs and informal employment.The two athletes are now training three times a week at the Instituto Reação. The learning curve has been steep. Geraldo Bernardes, the veteran coach of the Brazilian team in four Olympic Games, says that Misenga and Mabika were initially far too aggressive in training. “They were used to being punished and mistreated when they lost,” Geraldo explains. “I had to tell them that training and fighting are different things.”

Misenga told rio2016.com that he had adjusted to his new surrounds: “I have learnt a lot on the technical side. I can feel in my body that I have learnt what was missing before in my judo.” Their coach says the two judokas are rough diamonds and are still making up for the lost time in their training. Brazil has a strong tradition in the sport and both athletes are hoping that by refining their skills in the country they will make the cut when the IOC decides which athletes (from a shortlist of 43) will form part of Team Refugee in June. In the meantime, both Misenga and Mabika are enjoying their new lives in Rio. The Instituto Reação and the local Estácio de Sá university have given them the opportunity to learn Portuguese, maths and other subjects. Neither of the two judokas has any plan to leave the new home town that has given them so much.

(Available in: http://www.rio2016.com. Adapted.)

Analyse the sentence to answer 6.

Douglas had to apologize _________ little Jim’s mom _________ having played those pranks ______ her.

Choose the sequence to complete the blanks.

Analyse the sentence.

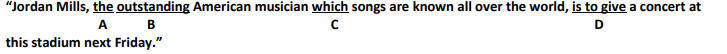

The item that contains an inconsistency and its corresponding correction is:

Analisando a imagem e tendo em vista o contexto da organização de um país e seus setores administrativos e econômicos, é correto afirmar que Dívida Pública é:

Do mercado financeiro a uma revolução no terceiro setor

Uma das brasileiras mais destacadas na Inglaterra, Daniela Barone fala sobre liderança feminina e Terceiro setor e dá dicas para quem está pensando em mudar de carreira.

Ela disse um sonoro não ao abonadíssimo mercado financeiro de Londres para começar do zero. Daniela Barone Soares, 40 anos, havia decidido que não correria mais atrás do primeiro milhão, do segundo… A virada aconteceu em 2004, exigiu a troca de apartamento e o corte de alguns mimos e fricotes, mas lhe caiu muito bem. Essa mineira de Belo Horizonte – aluna AAA do curso de economia da Unicamp (Universidade Estadual de Campinas) e pós-graduada na meca dos administradores, a escola de negócios de Harvard com bolsa da Fundação Estudar – é um dos nomes mais respeitados do terceiro setor na Inglaterra.

(Disponível em: https://www.napratica.org.br/do-mercado-financeiro-a-uma-revolucao-no-terceiro-setor.)

O terceiro setor corresponde basicamente:

“No ano passado o arquiteto José Ripper Kos participou de uma competição internacional para construir uma casa que consumisse a menor quantidade de energia. Depois do concurso, decidiu instalar em sua casa, um sistema de energia solar. Kos optou por painéis que gerassem energia a partir da luz solar. [...]”

(Revista Época, fevereiro de 2013.)

Os painéis citados no fragmento de texto anterior, que geram energia através da luz do sol são chamados de:

Os objetivos que a Educação Básica busca alcançar devem convergir para os princípios mais amplos que norteiam a Nação brasileira, expressos nas Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais, que são:

1. Princípios éticos.

2. Princípios políticos.

3. Princípios estéticos.

Relacione adequadamente os princípios aos seus conceitos.

( ) De reconhecimento dos direitos e deveres de cidadania, de respeito ao bem comum e à preservação do regime democrático e dos recursos ambientais.

( ) De justiça, solidariedade, liberdade e autonomia.

( ) De cultivo da sensibilidade juntamente com o da racionalidade; de enriquecimento das formas de expressão e do exercício da criatividade.

( ) De exigência de diversidade de tratamento para assegurar a igualdade de direitos entre os alunos que apresentam diferentes necessidades.

( ) De respeito à dignidade da pessoa humana e de compromisso com a promoção do bem de todos, contribuindo para combater e eliminar quaisquer manifestações de preconceito e discriminação.

( ) De busca da equidade no acesso à educação, à saúde, ao trabalho, aos bens culturais e outros benefícios.

( ) De valorização das diferentes manifestações culturais, especialmente as da cultura brasileira; de construção de identidades plurais e solidárias.

A sequência está correta em

De acordo com as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais, a necessária integração dos conhecimentos escolares no currículo favorece a sua contextualização e aproxima o processo educativo das experiências dos alunos. Neste documento legal, constituem exemplos de possibilidades de integração do currículo:

I. Projetos interdisciplinares com base em temas geradores formulados a partir de questões da comunidade.

II. Currículos em rede, propostas ordenadas em torno de conceitos-chave ou conceitos nucleares que permitam trabalhar as questões cognitivas e as questões culturais numa perspectiva transversal.

III. Projetos de trabalho com diversas acepções e propostas curriculares ordenadas em torno de grandes eixos disciplinares.

Está(ão) correta(s) a(s) afirmativa(s)

I. A escola não pode ser resumida apenas a um lugar de viabilização do poder ideológico dominante, a partir dos conteúdos curriculares que transmite aos alunos. II. Outros elementos característicos do sistema escolar merecem destaque e atenção cuidadosa, tais como: os métodos de avaliação da aprendizagem dos alunos, o exercício da prática pedagógica docente, a construção dos saberes escolares, a utilização dos recursos didático-pedagógicos no processo educativo etc. III.O caráter de autoridade multicultural do livro didático encontra sua legitimidade na crença de que ele é depositário de um saber a ser ‘decifrado’, pois se supõe que o livro-texto contenha uma verdade sacramentada a ser transmitida e compartilhada.

Estão corretas as afirmativas