Questões de Vestibular Comentadas sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 799 questões

Texto 1

Part of President Obama’s Speech at Rutgers Commencement 2016

Facts, evidence, reason, logic, an understanding of science — these are good things. These are qualities you want in people making policy. These are qualities you want to continue to cultivate in yourselves as citizens. That might seem obvious. That’s why we honor Bill Moyers or Dr. Burnell. We traditionally have valued those things. But if you were listening to today’s political debate, you might wonder where this strain of anti-intellectualism came from.

So, Class of 2016, let me be as clear as I can be. In politics and in life, ignorance is not a virtue. It’s not cool to not know what you’re talking about. That’s not keeping it real, or telling it like it is. That’s not challenging political correctness. That’s just not knowing what you’re talking about.

You know, it’s interesting that if we get sick, we actually want to make sure the doctors have gone to medical school, they know what they’re talking about. If we get on a plane, we say we really want a pilot to be able to pilot the plane. The rejection of facts, the rejection of reason and science — that is the path to decline.

From: shorturl.at/deAIX. Accessed on 04/01/2020

Texto 1

Part of President Obama’s Speech at Rutgers Commencement 2016

Facts, evidence, reason, logic, an understanding of science — these are good things. These are qualities you want in people making policy. These are qualities you want to continue to cultivate in yourselves as citizens. That might seem obvious. That’s why we honor Bill Moyers or Dr. Burnell. We traditionally have valued those things. But if you were listening to today’s political debate, you might wonder where this strain of anti-intellectualism came from.

So, Class of 2016, let me be as clear as I can be. In politics and in life, ignorance is not a virtue. It’s not cool to not know what you’re talking about. That’s not keeping it real, or telling it like it is. That’s not challenging political correctness. That’s just not knowing what you’re talking about.

You know, it’s interesting that if we get sick, we actually want to make sure the doctors have gone to medical school, they know what they’re talking about. If we get on a plane, we say we really want a pilot to be able to pilot the plane. The rejection of facts, the rejection of reason and science — that is the path to decline.

From: shorturl.at/deAIX. Accessed on 04/01/2020

Text 2

Home

No one leaves

home unless home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well

Your neighbors running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body

you only leave homewhen

home won‘t let you stay.

No one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it‘s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

and even then you carried the anthem under

your breath

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilet

sobbing as each mouthful of paper

made it clear that you wouldn‘t be going back.

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages (…)

I want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans (…)

No one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying –

leave,

run away from me now

I dont know what I‘ve become

but I know that anywhere

is safer than here.

By Warsan Shire. Disponível em: https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/many-faces-global-migration#8 Excertos.

Acesso em: set. 2020.

Text 2

Home

No one leaves

home unless home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well

Your neighbors running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body

you only leave homewhen

home won‘t let you stay.

No one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it‘s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

and even then you carried the anthem under

your breath

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilet

sobbing as each mouthful of paper

made it clear that you wouldn‘t be going back.

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages (…)

I want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans (…)

No one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying –

leave,

run away from me now

I dont know what I‘ve become

but I know that anywhere

is safer than here.

By Warsan Shire. Disponível em: https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/many-faces-global-migration#8 Excertos.

Acesso em: set. 2020.

Text 2

Home

No one leaves

home unless home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well

Your neighbors running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body

you only leave homewhen

home won‘t let you stay.

No one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it‘s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

and even then you carried the anthem under

your breath

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilet

sobbing as each mouthful of paper

made it clear that you wouldn‘t be going back.

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages (…)

I want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans (…)

No one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying –

leave,

run away from me now

I dont know what I‘ve become

but I know that anywhere

is safer than here.

By Warsan Shire. Disponível em: https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/many-faces-global-migration#8 Excertos.

Acesso em: set. 2020.

Text 1

What is Distance Learning and Why Is It So Important?

Text 1

What is Distance Learning and Why Is It So Important?

Text 1

What is Distance Learning and Why Is It So Important?

(“E-democracy and digital gaps”. www.svekom.se)

A ferramenta apresentada no excerto remete a uma característica da política ateniense no período clássico, que diz respeito

(Lucy Colback. www.ft.com, 28.02.2020. Adaptado.)

O excerto descreve mudanças nas relações geopolíticas entre Estados Unidos e China nas últimas décadas. Essas mudanças resultaram em

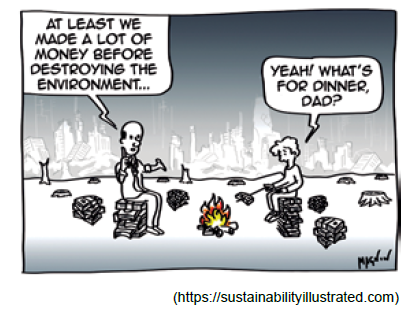

Analise o cartum.

A fala do personagem

O cartum dialoga com o seguinte trecho do texto “Education for Sustainable Development”: