Questões de Vestibular UNESP 2021 para Vestibular - Conhecimentos Gerais - Área de Exatas e Humanas

Foram encontradas 90 questões

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

When will the Amazon hit a tipping point?

Scientists say climate change, deforestation and fires could cause the world’s largest rainforest to dry out. The big question is how soon that might happen. Seen from a monitoring tower above the treetops near Manaus, in the Brazilian Amazon, the rainforest canopy stretches to the horizon as an endless sea of green. It looks like a rich and healthy ecosystem, but appearances are deceiving. This rainforest — which holds 16,000 separate tree species — is slowly drying out.

Over the past century, the average temperature in the forest has risen by 1-1.5 ºC. In some parts, the dry season has expanded during the past 50 years, from four months to almost five. Severe droughts have hit three times since 2005. That’s all driving a shift in vegetation. In 2018, a study reported that trees that do best in moist conditions, such as tropical legumes from the genus Inga, are dying. Those adapted to drier climes, such as the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), are thriving.

At the same time, large parts of the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, are being cut down and burnt. Tree clearing has already shrunk the forest by around 15% from its 1970s extent of more than 6 million square kilometres; in Brazil, which contains more than half the forest, more than 19% has disappeared. Last year, deforestation in Brazil spiked by around 30% to almost 10,000 km2 , the largest loss in a decade. And in August 2019, videos of wildfires in the Amazon made international headlines. The number of fires that month was the highest for any August since an extreme drought in 2010.

(www.nature.com, 25.02.2020. Adaptado.)

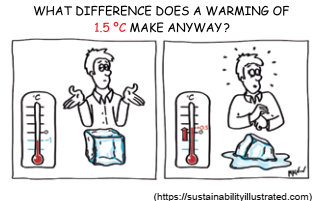

O cartum ilustra que o aumento de temperatura, também

citado no texto,

De acordo com o cartum,

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

Analise o mapa para responder à questão.

The business of climate change

A UN assessment published this week on the progress made in stemming the global loss of species made depressing reading. Not one of the 20 targets adopted by 196 countries in a convention on biodiversity in 2010 has been met. And the latest biennial Living Planet Report from the WWF, an environmental group, found that animal populations worldwide shrank by an average of two-thirds between 1970 and 2016. The falls were greatest in the tropics. In Latin America and the Caribbean animal populations fell by 94%, on average, during the period. It is some comfort that around the world biodiversity and climate change have become big political issues. In Australia koala bears have almost brought down a state government.

(www.economist.com, 18.09.2020.)

The business of climate change

A UN assessment published this week on the progress made in stemming the global loss of species made depressing reading. Not one of the 20 targets adopted by 196 countries in a convention on biodiversity in 2010 has been met. And the latest biennial Living Planet Report from the WWF, an environmental group, found that animal populations worldwide shrank by an average of two-thirds between 1970 and 2016. The falls were greatest in the tropics. In Latin America and the Caribbean animal populations fell by 94%, on average, during the period. It is some comfort that around the world biodiversity and climate change have become big political issues. In Australia koala bears have almost brought down a state government.

(www.economist.com, 18.09.2020.)

Entende-se hoje que a civilização medieval, apesar de limitada segundo os padrões atuais, dava ao homem um sentido de vida. Ele se via desempenhando um papel, por menor que fosse, de alcance amplo, importante para o equilíbrio do Universo. Não sofria, portanto, com o sentimento de substituibilidade que atormenta o homem contemporâneo. O medievo se sentia impotente diante da natureza, mas convivia bem com ela. O ocidental de hoje se sente a ponto de dominar a natureza, por isso se exclui dela.

(Hilário Franco Júnior. A Idade Média: nascimento do Ocidente, 1988.)

O “papel de alcance amplo”, “importante para o equilíbrio”,

representado pelas pessoas que viviam na Idade Média,

pode ser associado, entre outros fatores,

Entende-se hoje que a civilização medieval, apesar de limitada segundo os padrões atuais, dava ao homem um sentido de vida. Ele se via desempenhando um papel, por menor que fosse, de alcance amplo, importante para o equilíbrio do Universo. Não sofria, portanto, com o sentimento de substituibilidade que atormenta o homem contemporâneo. O medievo se sentia impotente diante da natureza, mas convivia bem com ela. O ocidental de hoje se sente a ponto de dominar a natureza, por isso se exclui dela.

(Hilário Franco Júnior. A Idade Média: nascimento do Ocidente, 1988.)

De maneira que, assim como a natureza faz de feras homens, matando e comendo, assim também a graça faz de feras homens, doutrinando e ensinando. Ensinastes o gentio bárbaro e rude, e que cuidais que faz aquela doutrina? Mata nele a fereza, e introduz a humanidade; mata a ignorância, e introduz o conhecimento; mata a bruteza, e introduz a razão; mata a infidelidade, e introduz a fé; e deste modo, por uma conversão admirável, o que era fera fica homem, o que era gentio fica cristão, o que era despojo do pecado fica membro de Cristo e de S. Pedro. […] Tende-os [os escravos], cristãos, e tende muitos, mas tende-os de modo que eles ajudem a levar a vossa alma ao céu, e vós as suas. Isto é o que vos desejo, isto é o que vos aconselho, isto é o que vos procuro, isto é o que vos peço por amor de Deus e por amor de vós, e o que quisera que leváreis deste sermão metido na alma.

(Antônio Vieira. “Sermão do Espírito Santo” (1657). http://tupi.fflch.usp.br.)

O Sermão do Espírito Santo foi pregado pelo Padre Antônio

Vieira em São Luís do Maranhão, em 1657, e recorre

Observe a gravura de Isidore-Stanislas Helman (1743-1806).

O evento representado na imagem mostra

No que dizia respeito ao Estado a ser construído, genericamente o modelo disponível era aquele que prevalecia no mundo ocidental. Tratava-se de organizar um aparato político-administrativo com jurisdição sobre um território definido, que exercia as competências de ditar as normas que deveriam regrar todos os aspectos da vida na sociedade, cobrar compulsoriamente tributos para financiá-lo e às suas políticas, exercer o poder punitivo para aqueles que não respeitassem as normas por ele ditadas.

(Miriam Dolhnikoff. História do Brasil império, 2019.)

O texto refere-se à organização política do Brasil após a independência, em 1822. O novo Estado brasileiro foi baseado em padrões

A classificação das raças em “superiores” e “inferiores”, recorrente desde o século XVII, ganha uma falsa legitimidade baseada no mito iluminista do saber científico, coincidindo com a necessária justificativa de que a dominação e a exploração da África, mais do que “naturais” e inevitáveis, eram “necessárias” para desenvolver os “selvagens” africanos, de acordo com as normas e os valores da civilização ocidental.

(Leila Leite Hernandez. A África na sala de aula: visita à história contemporânea, 2005.)

As teorias raciais utilizadas durante o processo de colonização da África no século XIX eram

Para Oswald, o primitivo estará associado ao pensamento selvagem como questionamento do pensamento iluminista e como proposta de valorização do pensamento selvagem local ao qual viria se acrescentar a incorporação contemporânea da técnica.

(Viviana Gelado. Poéticas da transgressão: vanguarda e cultura popular nos anos 20 na América Latina, 2006.)

O primitivismo expresso no “Manifesto da Poesia Pau-Brasil”,

lançado por Oswald de Andrade em 1924, pode ser associado à