Questões de Vestibular

Foram encontradas 106 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

In today’s political climate, it sometimes feels like we can’t even agree on basic facts. We bombard each other with statistics and figures, hoping that more data will make a difference. A progressive person might show you the same climate change graphs over and over while a conservative person might point to the trillions of dollars of growing national debt. We’re left wondering, “Why can’t they just see? It’s so obvious!”

Certain myths are so pervasive that no matter how many experts disprove them, they only seem to grow in popularity. There’s no shortage of serious studies showing no link between autism and vaccines, for example, but these are no match for an emotional appeal to parents worried for their young children.

Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, studies how our minds work and how we process new information. In her upcoming book, The Influential Mind, she explores why we ignore facts and how we can get people to actually listen to the truth. Tali shows that we’re open to new information – but only if it confirms our existing beliefs. We find ways to ignore facts that challenge our ideals. And as neuroscientist Bahador Bahrami and colleagues have found, we weigh all opinions as equally valid, regardless of expertise.

So, having the data on your side is not always enough. For better or for worse, Sharot says, emotions may be the key to changing minds.

(Shankar Vedantam. www.npr.org. Adaptado.)

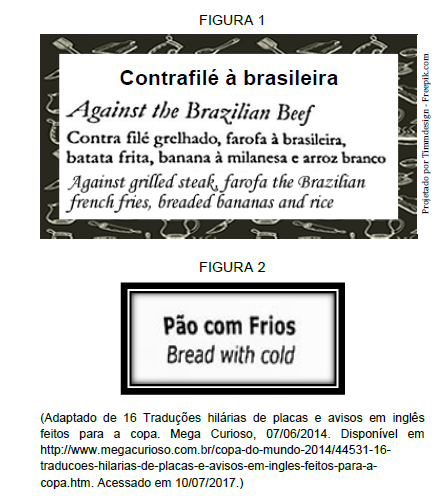

Entre as inadequações no uso do inglês observadas nas

figuras 1 e 2, podemos citar:

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)

TEXT

A library tradition is being refashioned to emphasize early literacy and better prepare young children for school, and drawing many new fans in the process.

Among parents of the under-5 set, spots for story time have become as coveted as seats for a hot Broadway show like “Hamilton.” Lines stretch down the block at some branches, with tickets given out on a first-come-first-served basis because there is not enough room to accommodate all of the children who show up.

Workers at the 67th Street Library on the Upper East Side of Manhattan turn away at least 10 people from every reading. They have been so overwhelmed by the rush at story time — held in the branch’s largest room, on the third floor — that once the space is full, they close the door and shut down the elevator. “It is so crowded and so popular, it’s insane,” Jacqueline Schector, a librarian, said.

Story time is drawing capacity crowds at public libraries across New York and across the country at a time when, more than ever, educators are emphasizing the importance of early literacy in preparing children for school and for developing critical thinking skills. The demand crosses economic lines, with parents at all income levels vying to get in.

Many libraries have refashioned the traditional readings to include enrichment activities such as counting numbers and naming colors, as well as music and dance. And many parents have made story time a fixture in their family routines alongside school pickups and playground outings — and, for those who employ nannies, a nonnegotiable requirement of the job.

In New York, demand for story time has surged across the city’s three library systems — the New York Public Library, the Brooklyn Public Library, and the Queens Library — and has posed logistical challenges for some branches, particularly those in small or cramped buildings. Citywide, story time attendance rose to 510,367 people in fiscal year 2015, up nearly 28 percent from 399,751 in fiscal 2013.

“The secret’s out,” said Lucy Yates, 44, an opera coach with two sons who goes to story time at the Fort Washington Library every week.

Stroller-pushing parents and nannies begin to line up for story time outside some branches an hour before doors open. To prevent overcrowding, tickets are given out at the New Amsterdam and Webster branches, both in Manhattan, the Parkchester branch in the Bronx, and a half-dozen branches in Brooklyn, including in Park Slope, Kensington and Bay Ridge.

The 67th Street branch keeps adding story times — there are now six a week — and holds sessions outdoors in the summer, when crowds can swell to 200 people.

In Queens, 41 library branches are scheduled to add weekend hours this month, and many will undoubtedly include weekend story times. As Joanne King, a spokeswoman for the library explained, parents have been begging for them and “every story time is full, every time we have one.”

Long a library staple, story time has typically been an informal reading to a small group of boys and girls sitting in a circle. Today’s story times involve carefully planned lessons by specially trained librarians that emphasize education as much as entertainment, and often include suggestions for parents and caregivers about how to reinforce what children have learned, library officials said.

Libraries around the country have expanded story time and other children’s programs in recent years, attracting a new generation of patrons in an age when online offerings sometimes make trips to the book stacks unnecessary. Sari Feldman, president of the American Library Association, said such early-literacy efforts are part of a larger transformation libraries are undergoing to become active learning centers for their communities by offering services like classes in English as a second language, computer skills and career counseling.

Ms. Feldman said the increased demand for story time was a product, in part, of more than a decade of work by the library association and others to encourage libraries to play a larger role in preparing young children for school. In 2004, as part of that effort, the association developed a curriculum, “Every Child Ready to Read,” that she said is now used by thousands of libraries.

The New York Public Library is adding 45 children’s librarians to support story time and other programs, some of which are run in partnership with the city government. It has also designated 20 of its 88 neighborhood branches, including the Fort Washington Library, as “enhanced literary sites.” As such, they will double their story time sessions, to an average of four a week, and distribute 15,000 “family literacy kits” that include a book and a schedule of story times.

“It is clear that reading and being exposed to books early in life are critical factors in student success,” Anthony W. Marx, president of the New York Public Library, said. “The library is playing an increasingly important role in strengthening early literacy in this city, expanding efforts to bring reading to children and their families through quality, free story times, curated literacy programs, after-school programs and more.”

For its part, the Queens Library plans to expand a “Kick Off to Kindergarten” program that attracted more than 180 families for a series of workshops last year. Library officials said that more than three-quarters of the children who enrolled, many of whom spoke a language other than English at home, developed measurable classroom skills.

From: www.nytimes.com/2015/11/02