Questões de Vestibular

Foram encontradas 196 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

In today’s political climate, it sometimes feels like we can’t even agree on basic facts. We bombard each other with statistics and figures, hoping that more data will make a difference. A progressive person might show you the same climate change graphs over and over while a conservative person might point to the trillions of dollars of growing national debt. We’re left wondering, “Why can’t they just see? It’s so obvious!”

Certain myths are so pervasive that no matter how many experts disprove them, they only seem to grow in popularity. There’s no shortage of serious studies showing no link between autism and vaccines, for example, but these are no match for an emotional appeal to parents worried for their young children.

Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, studies how our minds work and how we process new information. In her upcoming book, The Influential Mind, she explores why we ignore facts and how we can get people to actually listen to the truth. Tali shows that we’re open to new information – but only if it confirms our existing beliefs. We find ways to ignore facts that challenge our ideals. And as neuroscientist Bahador Bahrami and colleagues have found, we weigh all opinions as equally valid, regardless of expertise.

So, having the data on your side is not always enough. For better or for worse, Sharot says, emotions may be the key to changing minds.

(Shankar Vedantam. www.npr.org. Adaptado.)

In today’s political climate, it sometimes feels like we can’t even agree on basic facts. We bombard each other with statistics and figures, hoping that more data will make a difference. A progressive person might show you the same climate change graphs over and over while a conservative person might point to the trillions of dollars of growing national debt. We’re left wondering, “Why can’t they just see? It’s so obvious!”

Certain myths are so pervasive that no matter how many experts disprove them, they only seem to grow in popularity. There’s no shortage of serious studies showing no link between autism and vaccines, for example, but these are no match for an emotional appeal to parents worried for their young children.

Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, studies how our minds work and how we process new information. In her upcoming book, The Influential Mind, she explores why we ignore facts and how we can get people to actually listen to the truth. Tali shows that we’re open to new information – but only if it confirms our existing beliefs. We find ways to ignore facts that challenge our ideals. And as neuroscientist Bahador Bahrami and colleagues have found, we weigh all opinions as equally valid, regardless of expertise.

So, having the data on your side is not always enough. For better or for worse, Sharot says, emotions may be the key to changing minds.

(Shankar Vedantam. www.npr.org. Adaptado.)

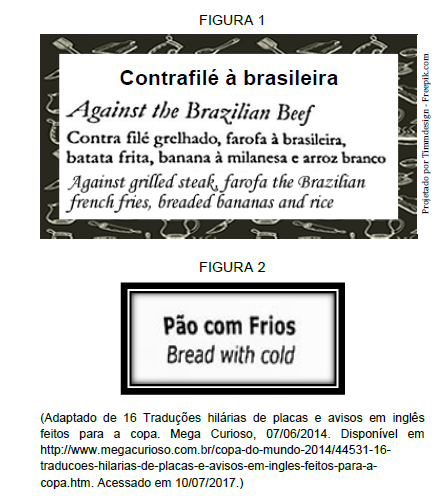

Entre as inadequações no uso do inglês observadas nas

figuras 1 e 2, podemos citar:

When does the brain work best?

The peak times and ages for learning

What’s your ideal time of the day for brain performance? Surprisingly, the answer to this isn’t as simple as being a morning or a night person. New research has shown that certain times of the day are best for completing specific tasks, and listening to your body’s natural clock may help you to accomplish more in 24 hours.

Science suggests that the best time for our natural peak productivity is late morning. Our body temperatures start to rise just before we wake up in the morning and continue to increase through midday, Steve Kay, a professor of molecular and computational biology at the University of Southern California told The Wall Street Journal. This gradual increase in body temperature means that our working memory, alertness, and concentration also gradually improve, peaking at about mid morning. Our alertness tends to dip after this point, but one study suggested that midday fatigue may actually boost our creative abilities. For a 2011 study, 428 students were asked to solve a series of two types of problems, requiring either analytical or novel thinking. Results showed that their performance on the second type was best at non-peak times of day when they were tired.

As for the age where our brains are at peak condition, science has long held that fluid intelligence, or the ability to think quickly and recall information, peaks at around age 20. However, a 2015 study revealed that peak brain age is far more complicated than previously believed and concluded that there are about 30 subsets of intelligence, all of which peak at different ages for different people. For example, the study found that raw speed in processing information appears to peak around age 18 or 19, then immediately starts to decline, but short-term memory continues to improve until around age 25, and then begins to drop around age 35, Medical Xpress reported. The ability to evaluate other people’s emotional states peaked much later, in the 40s or 50s. In addition, the study suggested that out our vocabulary may peak as late as our 60s’s or 70’s.

Still, while working according to your body’s natural clock may sound helpful, it’s important to remember that these times may differ from person to person. On average, people can be divided into two distinct groups: morning people tend to wake up and go to sleep earlier and to be most productive early in the day. Evening people tend to wake up later, start more slowly and peak in the evening. If being a morning or evening person has been working for you the majority of your life, it may be best to not fix what’s not broken.

(Dana Dovey. www.medicaldaily.com, 08.08.2016. Adaptado.)

“One never builds something finished”:

the brilliance of architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Oliver Wainwright

February 4, 2017

“All space is public,” says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the 88-year-old Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody,” he says, “not just for the very few.”

(www.theguardian.com. Adaptado.)