Questões Militares Comentadas sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 2.962 questões

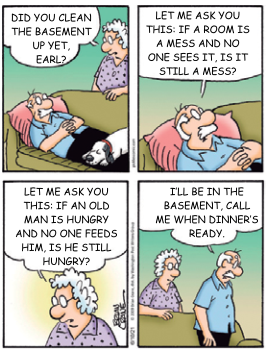

Leia a tirinha Pickles de Brian Crane.

(www.gocomics.com)

A leitura dos dois últimos quadrinhos da tirinha permite inferir que a mulher é uma pessoa

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

While plastic refuse littering beaches and oceans draws high-profile attention, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: a call for action suggests that the land we use to grow our food is contaminated with even larger quantities of plastic pollutants. “Soils are one of the main receptors of agricultural plastics and are known to contain larger quantities of microplastics than oceans”, FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo said in the report’s foreword.

According to data collated by FAO experts, agricultural value chains each year use 12.5 million tonnes of plastic products while another 37.3 million are used in food packaging. Crop production and livestock accounted for 10.2 million tonnes per year collectively, followed by fisheries and aquaculture with 2.1 million, and forestry with 0.2 million tonnes. Asia was estimated to be the largest user of plastics in agricultural production, accounting for almost half of global usage. Moreover, without viable alternatives, plastic demand in agriculture is only set to increase. As the demand for agricultural plastic continues surge, Ms. Semedo underscored the need to better monitor the quantities that “leak into the environment from agriculture”.

Since their widespread introduction in the 1950s, plastics have become ubiquitous. In agriculture, plastic products greatly help productivity, such as in covering soil to reduce weeds; nets to protect and boost plant growth, extend cropping seasons and increase yields; and tree guards, which protect young plants and trees from animals and help provide a growth-enhancing microclimate. However, of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastics produced before 2015, almost 80 per cent had never been properly disposed of. While the effects of large plastic items on marine fauna have been well documented, the impacts unleashed during their disintegration potentially affect entire ecosystems.

(https://news.un.org, 07.12.2021. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

While plastic refuse littering beaches and oceans draws high-profile attention, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: a call for action suggests that the land we use to grow our food is contaminated with even larger quantities of plastic pollutants. “Soils are one of the main receptors of agricultural plastics and are known to contain larger quantities of microplastics than oceans”, FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo said in the report’s foreword.

According to data collated by FAO experts, agricultural value chains each year use 12.5 million tonnes of plastic products while another 37.3 million are used in food packaging. Crop production and livestock accounted for 10.2 million tonnes per year collectively, followed by fisheries and aquaculture with 2.1 million, and forestry with 0.2 million tonnes. Asia was estimated to be the largest user of plastics in agricultural production, accounting for almost half of global usage. Moreover, without viable alternatives, plastic demand in agriculture is only set to increase. As the demand for agricultural plastic continues surge, Ms. Semedo underscored the need to better monitor the quantities that “leak into the environment from agriculture”.

Since their widespread introduction in the 1950s, plastics have become ubiquitous. In agriculture, plastic products greatly help productivity, such as in covering soil to reduce weeds; nets to protect and boost plant growth, extend cropping seasons and increase yields; and tree guards, which protect young plants and trees from animals and help provide a growth-enhancing microclimate. However, of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastics produced before 2015, almost 80 per cent had never been properly disposed of. While the effects of large plastic items on marine fauna have been well documented, the impacts unleashed during their disintegration potentially affect entire ecosystems.

(https://news.un.org, 07.12.2021. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

While plastic refuse littering beaches and oceans draws high-profile attention, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: a call for action suggests that the land we use to grow our food is contaminated with even larger quantities of plastic pollutants. “Soils are one of the main receptors of agricultural plastics and are known to contain larger quantities of microplastics than oceans”, FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo said in the report’s foreword.

According to data collated by FAO experts, agricultural value chains each year use 12.5 million tonnes of plastic products while another 37.3 million are used in food packaging. Crop production and livestock accounted for 10.2 million tonnes per year collectively, followed by fisheries and aquaculture with 2.1 million, and forestry with 0.2 million tonnes. Asia was estimated to be the largest user of plastics in agricultural production, accounting for almost half of global usage. Moreover, without viable alternatives, plastic demand in agriculture is only set to increase. As the demand for agricultural plastic continues surge, Ms. Semedo underscored the need to better monitor the quantities that “leak into the environment from agriculture”.

Since their widespread introduction in the 1950s, plastics have become ubiquitous. In agriculture, plastic products greatly help productivity, such as in covering soil to reduce weeds; nets to protect and boost plant growth, extend cropping seasons and increase yields; and tree guards, which protect young plants and trees from animals and help provide a growth-enhancing microclimate. However, of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastics produced before 2015, almost 80 per cent had never been properly disposed of. While the effects of large plastic items on marine fauna have been well documented, the impacts unleashed during their disintegration potentially affect entire ecosystems.

(https://news.un.org, 07.12.2021. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

While plastic refuse littering beaches and oceans draws high-profile attention, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: a call for action suggests that the land we use to grow our food is contaminated with even larger quantities of plastic pollutants. “Soils are one of the main receptors of agricultural plastics and are known to contain larger quantities of microplastics than oceans”, FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo said in the report’s foreword.

According to data collated by FAO experts, agricultural value chains each year use 12.5 million tonnes of plastic products while another 37.3 million are used in food packaging. Crop production and livestock accounted for 10.2 million tonnes per year collectively, followed by fisheries and aquaculture with 2.1 million, and forestry with 0.2 million tonnes. Asia was estimated to be the largest user of plastics in agricultural production, accounting for almost half of global usage. Moreover, without viable alternatives, plastic demand in agriculture is only set to increase. As the demand for agricultural plastic continues surge, Ms. Semedo underscored the need to better monitor the quantities that “leak into the environment from agriculture”.

Since their widespread introduction in the 1950s, plastics have become ubiquitous. In agriculture, plastic products greatly help productivity, such as in covering soil to reduce weeds; nets to protect and boost plant growth, extend cropping seasons and increase yields; and tree guards, which protect young plants and trees from animals and help provide a growth-enhancing microclimate. However, of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastics produced before 2015, almost 80 per cent had never been properly disposed of. While the effects of large plastic items on marine fauna have been well documented, the impacts unleashed during their disintegration potentially affect entire ecosystems.

(https://news.un.org, 07.12.2021. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

While plastic refuse littering beaches and oceans draws high-profile attention, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Assessment of agricultural plastics and their sustainability: a call for action suggests that the land we use to grow our food is contaminated with even larger quantities of plastic pollutants. “Soils are one of the main receptors of agricultural plastics and are known to contain larger quantities of microplastics than oceans”, FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo said in the report’s foreword.

According to data collated by FAO experts, agricultural value chains each year use 12.5 million tonnes of plastic products while another 37.3 million are used in food packaging. Crop production and livestock accounted for 10.2 million tonnes per year collectively, followed by fisheries and aquaculture with 2.1 million, and forestry with 0.2 million tonnes. Asia was estimated to be the largest user of plastics in agricultural production, accounting for almost half of global usage. Moreover, without viable alternatives, plastic demand in agriculture is only set to increase. As the demand for agricultural plastic continues surge, Ms. Semedo underscored the need to better monitor the quantities that “leak into the environment from agriculture”.

Since their widespread introduction in the 1950s, plastics have become ubiquitous. In agriculture, plastic products greatly help productivity, such as in covering soil to reduce weeds; nets to protect and boost plant growth, extend cropping seasons and increase yields; and tree guards, which protect young plants and trees from animals and help provide a growth-enhancing microclimate. However, of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastics produced before 2015, almost 80 per cent had never been properly disposed of. While the effects of large plastic items on marine fauna have been well documented, the impacts unleashed during their disintegration potentially affect entire ecosystems.

(https://news.un.org, 07.12.2021. Adaptado.)

Read the text and answer the question.

Camping

On Sunday morning, Tom and his family went camping. They camped near the lake. Their tent was shaped like an igloo. It was made of a thin cloth. Tom helped clean up. They ate a tasty meal of barbecued chicken and corn. When it got dark they made a fire. They told stories and sang songs.

English Created Resources.

Read the text and answer the question.

Camping

On Sunday morning, Tom and his family went camping. They camped near the lake. Their tent was shaped like an igloo. It was made of a thin cloth. Tom helped clean up. They ate a tasty meal of barbecued chicken and corn. When it got dark they made a fire. They told stories and sang songs.

English Created Resources.

Read the text and answer the question.

On top of the World-Imagine Dragons

If you love somebody

Better tell them why they’re here cause

They just may run away from you

You will never know what went well

Then again it just depends on

How long of time is left for you

I’ve had the highest mountains

I’ve had the deepest rivers

You can have it all but not til you move it

Now take it in but don’t look down.

www.vagalume.com.br.

Read the text and answer the question.

On top of the World-Imagine Dragons

If you love somebody

Better tell them why they’re here cause

They just may run away from you

You will never know what went well

Then again it just depends on

How long of time is left for you

I’ve had the highest mountains

I’ve had the deepest rivers

You can have it all but not til you move it

Now take it in but don’t look down.

www.vagalume.com.br.

Match the words according to their synonyms:

1 – strong

2 – hungry

3 – gorgeous

4 – intelligent

( ) clever

( ) powerful

( ) beautiful

( ) starving

Read the text and answer the question.

Tower Bridge

John Hughes and Ceri Jones

Tower Bridge is probably the most famous bridge in London. It is called Tower Bridge because it is located near the Tower of London. The City of London first started to plan a new bridge across the Thames in 1876. More than 50 designs _________ (to receive) and it took eight years for the judges to choose the winning design.

From the book Practical Grammar Level 2

Read the text and answer the question.

Tower Bridge

John Hughes and Ceri Jones

Tower Bridge is probably the most famous bridge in London. It is called Tower Bridge because it is located near the Tower of London. The City of London first started to plan a new bridge across the Thames in 1876. More than 50 designs _________ (to receive) and it took eight years for the judges to choose the winning design.

From the book Practical Grammar Level 2

Read the text and answer the question.

Dear Toti,

I’m writing to you from my hotel room. Everyone else is sleeping, but I’m sitting here and watching the ocean. We’re staying at the Plaza in Atlantic Beach, and the view is beautiful. The tour is goes well. The audience is crazy about the new songs, but the fans are always asking for you. How is the baby? She has a great voice. Are you teaching her to sing yet? Maybe both of you will come along for the next tour!

Sylvia

From the book Grammar Express

Read the text and answer the question.

Dear Toti,

I’m writing to you from my hotel room. Everyone else is sleeping, but I’m sitting here and watching the ocean. We’re staying at the Plaza in Atlantic Beach, and the view is beautiful. The tour is goes well. The audience is crazy about the new songs, but the fans are always asking for you. How is the baby? She has a great voice. Are you teaching her to sing yet? Maybe both of you will come along for the next tour!

Sylvia

From the book Grammar Express

Read the sentences below.

1. Andy reads comic books.

2. Sandy sings in the bathroom.

3. My sister helps in the kitchen.

The verbs in bold are in the:

Read the text and answer the question.

Read the conversation between Carol and Neil.

Neil: What do you do on New Year’s Day?

Carol: Well, we sometimes go downtown. They have fireworks. It’s really pretty. Other people invite friends to their house and they have a party.

Neil: Do you give presents to your friends and family?

Carol: No, we never give presents on New Year’s.

Neil: Do you have a meal with your family?

Carol: No, we do that on Christmas. On New Year’s we just party!

From the Book World English 1A