Questões Militares

Para segurança pública

Foram encontradas 6.543 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

No que se refere às funções das estruturas celulares que constituem as células procarióticas e eucarióticas, julgue o item seguinte.

A capacidade de locomoção de uma célula procariótica deve-se

à presença de um citoesqueleto composto de filamentos

proteicos.

A respeito das propriedades químicas e físicas de determinados combustíveis, julgue o próximo item.

A gasolina é uma substância orgânica que reage com o

oxigênio do ar.

A respeito das propriedades químicas e físicas de determinados combustíveis, julgue o próximo item.

O etanol é uma substância inorgânica.

Com relação ao funcionamento desses tipos de extintores e aos seus componentes químicos, julgue o item a seguir.

A substância do extintor de pó químico é formada por ligações

covalentes e iônicas.

Com relação ao funcionamento desses tipos de extintores e aos seus componentes químicos, julgue o item a seguir.

No texto, são apresentadas fórmulas que contêm átomos de

elementos químicos de não metal e de um metal de transição.

Com relação ao funcionamento desses tipos de extintores e aos seus componentes químicos, julgue o item a seguir.

Quando em funcionamento, o extintor de espuma facilita o

contato do comburente com o combustível.

Com relação ao funcionamento desses tipos de extintores e aos seus componentes químicos, julgue o item a seguir.

A primeira substância citada no texto — NaHCO3 — pode ser

formada pela adição de CO2 a uma solução de hidróxido de

sódio.

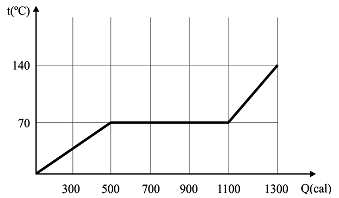

A figura seguinte mostra o gráfico da temperatura em função da quantidade de calor absorvida por 50 gramas de uma substância, inicialmente, no estado líquido.

Com referência ao gráfico precedente, julgue o item a seguir.

Durante toda a mudança de fase a substância absorveu 600 cal

de calor.

O circuito mostrado na figura a seguir é constituído de uma fonte com força eletromotriz ε = 35 V, dos resistores R1 = 1 Ω, R2 = 2 Ω, R3 = 3 Ω e R4 = 4 Ω, e das chaves liga-desliga S1 e S2.

Considerando que todos os elementos desse circuito sejam ideais, julgue o item seguinte.

Na situação de equilíbrio, quando a chave S1 estiver aberta e a

S2 fechada, a corrente que passa por R1 é menor que 3,0 A.

O circuito mostrado na figura a seguir é constituído de uma fonte com força eletromotriz ε = 35 V, dos resistores R1 = 1 Ω, R2 = 2 Ω, R3 = 3 Ω e R4 = 4 Ω, e das chaves liga-desliga S1 e S2.

Considerando que todos os elementos desse circuito sejam ideais, julgue o item seguinte.

Na situação de equilíbrio, se as chaves S1 e S2 estiverem

fechadas, a diferença de potencial entre os pontos B e E será a

mesma que entre os pontos E e D.

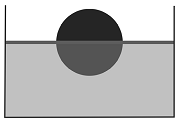

A figura precedente mostra uma esfera homogênea de volume V flutuando em um líquido de densidade constante igual a ρ; metade da esfera está submersa.

Considerando que a densidade da esfera seja constante e igual a ρe, julgue o próximo item.

Na situação de equilíbrio, a densidade ρ do líquido é igual a

duas vezes a densidade ρe, isto é, ρ = 2ρe.

A figura a seguir mostra um sistema de roldanas utilizado

para resgatar um homem de 80 kg.

Considerando a figura, que as roldanas sejam ideais, os fios inextensíveis e que a gravidade local seja igual a 10 m/s2 , julgue o item a seguir.

Para suspender o homem, a força F a ser aplicada pela equipe

de resgate deverá ser igual a 450 N.

A figura a seguir mostra um sistema de roldanas utilizado

para resgatar um homem de 80 kg.

Considerando a figura, que as roldanas sejam ideais, os fios inextensíveis e que a gravidade local seja igual a 10 m/s2 , julgue o item a seguir.

Se a corda presa ao homem a ser resgatado se romper quando

ele estiver a 3,2 m do solo, ele chegará ao solo com uma

velocidade superior a 10 m/s.

Julgue o próximo item, relativo ao disposto no Estatuto dos Policiais Militares do Estado de Alagoas e nas legislações estaduais que tratam dos critérios e das condições de acesso na hierarquia militar.

O ingresso na Polícia Militar do Estado de Alagoas é privativo

a brasileiro nato, sem distinção de raça, sexo, cor ou credo

religioso, e ocorre por meio de matrícula ou nomeação depois

de aprovação em concurso público, desde que observadas as

condições determinadas no regulamento da corporação.

Julgue o próximo item, relativo ao disposto no Estatuto dos Policiais Militares do Estado de Alagoas e nas legislações estaduais que tratam dos critérios e das condições de acesso na hierarquia militar.

Situação hipotética: Durante um incêndio em determinado

edifício, um bombeiro militar constatou que duas crianças

estavam presas no prédio. Audaciosamente e com coragem,

além do cumprimento do dever legal, o bombeiro entrou no

prédio e resgatou as crianças e, em razão do ato, ele inalou

muita fumaça e sofreu graves escoriações. Assertiva: Nessa

situação, o militar poderá ser promovido por ato de bravura,

independentemente da existência de vaga.

Julgue o próximo item, relativo ao disposto no Estatuto dos Policiais Militares do Estado de Alagoas e nas legislações estaduais que tratam dos critérios e das condições de acesso na hierarquia militar.

Considera-se mais antigo, para fins de promoção, o militar que

tenha obtido, ao final do curso de formação complementar de

praça, maior grau de aproveitamento intelectual em relação aos

demais militares da sua turma.

À luz do Regulamento Disciplinar da Polícia Militar do Estado de Alagoas, julgue o item subsequente.

Denomina-se parte disciplinar o documento obrigatório que é

dirigido à autoridade competente e que contém a narração, por

escrito, de fato ou ato de natureza disciplinar praticado por

militar de posto ou de graduação inferior à do signatário.

À luz do Regulamento Disciplinar da Polícia Militar do Estado de Alagoas, julgue o item subsequente.

Configura transgressão disciplinar leve o não encaminhamento,

pelo oficial ao escalão superior, de comunicação de

subordinado a respeito de impetração de recurso sobre ato

administrativo junto ao Poder Judiciário.

À luz do Regulamento Disciplinar da Polícia Militar do Estado de Alagoas, julgue o item subsequente.

As transgressões disciplinares classificam-se, de acordo com

a sua intensidade, em leves, médias, graves ou gravíssimas.

Com base no Estatuto dos Policiais Militares do Estado de Alagoas, julgue o item a seguir.

A graduação é grau hierárquico exclusivo dos oficiais, sendo

conferido pelo chefe do Poder Executivo.