Questões de Concurso Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 17.320 questões

INSTRUÇÃO: Leia o texto a seguir para responder à questão.

Brazil’s Supreme Court to vote on decriminalising abortion

By Katy Watson

Brazil’s Supreme Court has started voting on whether to decriminalise abortion. However, the session was quickly postponed after a minister called for the vote to take place in person instead of via video – and no new date has yet been set.

Currently, abortion is only allowed in three cases: that of rape, risk to the woman's life and anencephaly – when the foetus has an undeveloped brain.

If the Supreme Court votes in favour, abortion will be decriminalised up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. [...]

Disponível em: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-66881900. Acesso em: 25 set. 2023. Adaptado.

Harrisburg: A convicted murderer who escaped from a Pennsylvania jail has been captured with help from a heatsensing aircraft and a police dog, ending an intense, two-week manhunt that unnerved residents in the Philadelphia suburbs, authorities said.

Tactical teams surrounded the fugitive, Danelo Cavalcante, at around 8am in a rural area about 50 kilometres west of Philadelphia. As he tried to crawl away, a police dog subdued him and he was forcibly taken into custody, Pennsylvania State Police Lieutenant Colonel George Bivens said.

Cavalcante, who was armed with a rifle that he had stolen from a garage, was taken into custody without further incident. Bivens said he did not have the opportunity to use the firearm.

Cavalcante broke out of the Chester County Prison two weeks earlier by climbing between two walls that formed a narrow corridor in the jailhouse yard and scrambling onto the roof, according to police.

“It’s never easy to find someone who doesn’t want to be found in a large area,” Bivens said in response to a question about the extended manhunt during a Wednesday news briefing.

Disponível em: https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/fugitive-captured-ending-two-week-manhunt-in-us-20230914-p5e4im.html. Acesso em: 15 set. 2023. Adaptado.

A seleção apropriada dos tempos verbais na redação assume um caráter crucial, visto que visa assegurar a clareza e a coesão do texto, fomentando assim a fluidez da leitura. Esse aspecto é de particular relevância em uma composição jornalística, em que se impõe a necessidade de determinar com exatidão a temporalidade das informações veiculadas, o que, por sua vez, confere credibilidade à reportagem, manifestando um zelo pelo rigor e precisão na exposição dos fatos.

Considerando as duas passagens negritadas no texto, o que indica a escolha das estruturas verbais nesses trechos destacados?

INSTRUÇÃO: Leia o texto a seguir para responder à questão 06.

Convicted Brazilian fugitive captured, ending two-week manhunt in US

Harrisburg: A convicted murderer who escaped from a Pennsylvania jail has been captured with help from a heat-sensing aircraft and a police dog, ending an intense, two-week manhunt that unnerved residents in the Philadelphia suburbs, authorities said.

Tactical teams surrounded the fugitive, Danelo Cavalcante, at around 8am in a rural area about 50 kilometres west of Philadelphia. As he tried to crawl away, a police dog subdued him and he was forcibly taken into custody, Pennsylvania State Police Lieutenant Colonel George Bivens said.

Cavalcante, who was armed with a rifle that he had stolen from a garage, was taken into custody without further incident. Bivens said he did not have the opportunity to use the firearm.

Cavalcante broke out of the Chester County Prison two weeks earlier by climbing between two walls that formed a narrow corridor in the jailhouse yard and scrambling onto the roof, according to police.

“It’s never easy to find someone who doesn’t want to be found in a large area,” Bivens said in response to a question about the extended manhunt during a Wednesday news briefing.

Disponível em: https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/fugitive-captured-ending-two-week-manhunt-in-us-20230914-p5e4im.html.

Acesso em: 15 set. 2023. Adaptado.

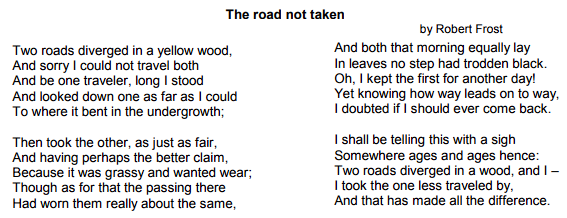

INSTRUÇÃO: Leia o texto a seguir para responder à questão.

Disponível em: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44272/the-road-not-taken. Acesso em: 23 set. 2023.

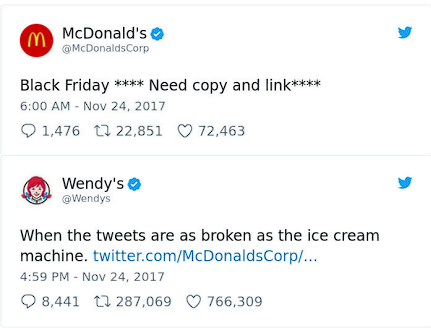

INSTRUÇÃO: O texto a seguir refere-se à questão. Leia-o atentamente.

Disponível em: https://alidropship.com/funny-tweets-for-brand-engagement/. Acesso em: 23 set. 2023.

Tanto o Wendy’s quanto o McDonald’s são redes de restaurantes de “fast food” que oferecem refeições preparadas

rapidamente para consumo no local, para viagem ou por meio de serviços de entrega. Em 24 de novembro de 2017,

a rede McDonald's realizou uma postagem na sua conta, em uma rede social, e foi prontamente respondida pela

franquia concorrente, Wendy’s. Baseando-se na imagem, qual foi a intenção da rede Wendy’s?

INSTRUÇÃO: Leia o texto a seguir para responder à questão.

The counteroffensive may be flagging, but Crimea attack shows Ukraine can still inflict serious damage on the Russian military

On Wednesday, a large plume of smoke rose from a naval base near Sevastopol. Local authorities played down the incident, saying that a number of drones were brought down. But the Ukrainian military says it successfully hit a Russian command post near Verkhniosadove, a few kilometers from Sevastopol.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) noted that satellite imagery confirmed that Ukrainian forces “struck the 744th Communications Center of the Command of the Black Sea FleetD as part of an apparent Ukrainian effort to target Black Sea Fleet facilities.”

Fonte: LISTER, T. Disponível em: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/22/europe/ukraine-crimea-russia-black-sea-intl-cmd/index.html. Acesso em: 23

set. 2023. Adaptado.

( ) Many believe AI will eventually make jobs redundant.

( ) The conclusion of the text is that the current outlook regarding employment is rather bleak.

( ) The authors prefer to probe forthcoming evidence before issuing unequivocal accounts.

The statements are, respectively,

Text I

Text I

Text I

( ) The dawning of generative art has given rise to a quandary.

( ) The winner mentioned was thrilled with the prize he was awarded.

( ) The organization responsible for the award stood by their earlier statement that AI yields finer art than that of humans.

The statements are, respectively,