Questões de Concurso Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 17.034 questões

The ___ is the last paragraph of this test's text.

In the utterance " …) and regulate the reading as it occurs", taken from the 2nd paragraph of the text, the underlined clause can be replaced by ____

We must use reading strategies ____ text we face.

Bottom-up and top-down are ____ cognitive strategies.

In the utterance "

…) and self-evaluation of learning after the language activity is completed", takenfrom the 2nd paragraph of the text, the underlined word functions as a ____.

In the utterance " (...readers check to see how this information fits ...)", taken from the 5th paragraph of the text, the underlined word can be replaced by ____.

In the utterance " …) which means that they focus on identification …)", taken from the 5th paragraph of the text, the underlined word refers to ____.

[…]

Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org.br/sites/default/files/leitura_critica_bncc_-_en_-_v4_final.pdf. [Fragment]. Accessed on May 6, 2024.

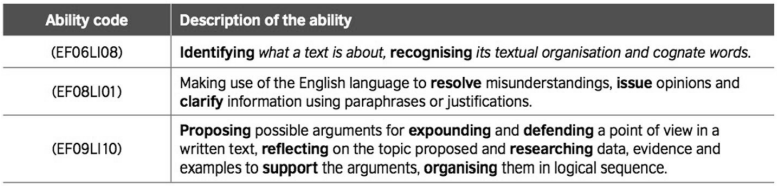

To develop the BNCC ability of identifying what a text is about and recognising its textual organization and cognate words, English teachers are recommended to exploit different textual genres in the language classroom. Examples of such texts range from a menu, a text message or a poem to a book review.

To develop the BNCC ability EF06LI08, which includes identifying what a text is about, an English teacher should make use of

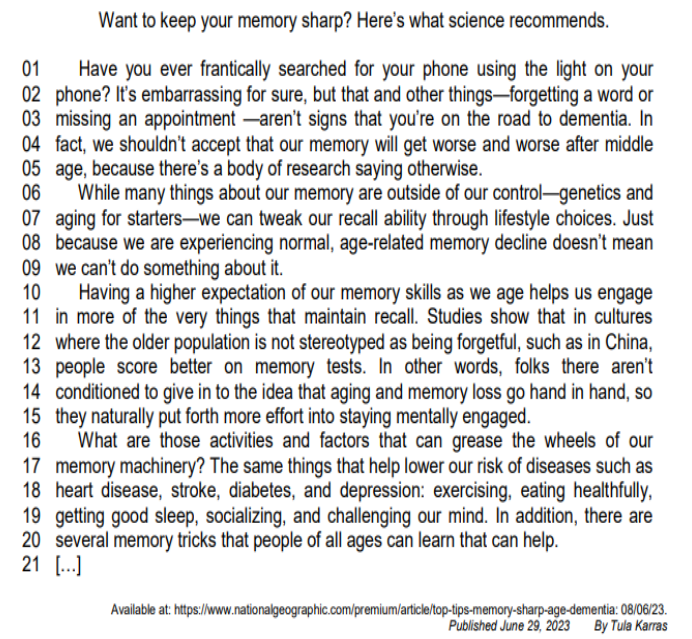

Read the following text to answer the question.

By Leo Selivan

In this article, informed by the Lexical Approach, I reflect on grammar instruction in the classroom […]. I consider the problems with ‘traditional’ grammar teaching before arguing that what we actually need is more grammar input as well as showing how lexis can provide necessary ‘crutches’ for the learner.

Lexis = vocabulary + grammar

The shift in ELT from grammar to lexis mirrors a similar change in the attitude of linguists. In the past linguists were preoccupied with the grammar of language; however the advances in corpus linguistics have pushed lexis to the forefront. The term ‘lexis’, which was traditionally used by linguists, is a common word these days and frequently used even in textbooks.

Why use a technical term borrowed from the realm of linguistics instead of the word ‘vocabulary’? Quite simply because vocabulary is typically seen as individual words (often presented in lists) whereas lexis is a somewhat wider concept and consists of collocations, chunks and formulaic expressions. It also includes certain patterns that were traditionally associated with the grammar of a language, e.g. If I were you…, I haven’t seen you for ages etc.

Recognising certain grammar structures as lexical

items means that they can be introduced much earlier,

without structural analysis or elaboration. Indeed, since the

concept of notions and functions made its way into language

teaching, particularly as Communicative Language Teaching

(CLT) gained prominence, some structures associated with

grammar started to be taught lexically (or functionally). I’d like

to is not taught as ‹the conditional› but as a chunk expressing

desire. Similarly many other ‹traditional› grammar items can

be introduced lexically relatively early on.

Less grammar or more grammar?

You are, no doubt, all familiar with students who on one hand seem to know the ‘rules’ of grammar but still fail to produce grammatically correct sentences when speaking or, on the other, sound unnatural and foreign-like even when their sentences are grammatically correct. Michael Lewis, who might be considered the founder of the Lexical Approach, once claimed that there was no direct relationship between the knowledge of grammar and speaking. In contrast, the knowledge of formulaic language has been shown by research to have a significant bearing on the natural language production.

Furthermore, certain grammar rules are practically impossible to learn. Dave Willis cites the grammar of orientation (which includes the notoriously difficult present perfect and the uses of certain modal verbs) as particularly resistant to teaching. The only way to grasp their meaning is through continuous exposure and use.

Finally, even the most authoritative English grammars never claim to provide a comprehensive description of all the grammar, hence the word ‘introduction’ often used in their titles (for instance, Huddleston & Pullum’s A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar or Halliday’s An Introduction to Functional Grammar).

If grammarians do not even attempt to address all areas of grammar, how can we, practitioners, cover all the aspects of grammar in our teaching, especially if all we seem to focus on is a limited selection of discrete items, comprised mostly of tenses and a handful of modal verbs? It would seem that we need to expose our students to a lot of naturally occurring language and frequently draw their attention to various grammar points as they arise.

For example, while teaching the expression fall asleep / be asleep you can ask your students:

• Don’t make any noise – she’s fallen asleep.

• Don’t make any noise – she’s asleep.

What does’s stand for in each of these cases (is or has)?

One of the fathers of the Communicative Language Teaching Henry Widdowson advocated using lexical items as a starting point and then ‘showing how they need to be grammatically modified to be communicatively effective’ (1990:95). For example, when exploring a text with your students, you may come across a sentence like this:

• They’ve been married for seven years.

You can ask your students: When did they get married? How should you change the sentence if the couple you are talking about is no longer married?

The above demonstrates how the teacher should be constantly on the ball and take every opportunity to draw students’ attention to grammar. Such short but frequent ‘grammar spots’ will help to slowly raise students’ awareness and build their understanding of the English grammar system.

[…]

Conclusion

So is there room for grammar instruction in the classroom? Certainly yes. But the grammar practice should always start with the exploitation of lexical items. Exposing students to a lot of natural and contextualised examples will offer a lexical way into the grammar of the language.

To sum up, grammar should play some role in language teaching but should not occupy a big part of class time. Instead grammar should be delivered in small but frequent portions. Students should be encouraged to collect a lot of examples of a particular structure before being invited to analyse it. Hence, analysis should be preceded by synthesis.

Lastly, language practitioners should bear in mind that grammar acquisition is an incremental process which requires frequent focus and refocus on the items already studied.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professionaldevelopment/teachers/knowing-subject/articles/grammar-vs-lexisor-grammar-through. Accessed on: April 29, 2024.

Read the following text to answer the question.

By Leo Selivan

In this article, informed by the Lexical Approach, I reflect on grammar instruction in the classroom […]. I consider the problems with ‘traditional’ grammar teaching before arguing that what we actually need is more grammar input as well as showing how lexis can provide necessary ‘crutches’ for the learner.

Lexis = vocabulary + grammar

The shift in ELT from grammar to lexis mirrors a similar change in the attitude of linguists. In the past linguists were preoccupied with the grammar of language; however the advances in corpus linguistics have pushed lexis to the forefront. The term ‘lexis’, which was traditionally used by linguists, is a common word these days and frequently used even in textbooks.

Why use a technical term borrowed from the realm of linguistics instead of the word ‘vocabulary’? Quite simply because vocabulary is typically seen as individual words (often presented in lists) whereas lexis is a somewhat wider concept and consists of collocations, chunks and formulaic expressions. It also includes certain patterns that were traditionally associated with the grammar of a language, e.g. If I were you…, I haven’t seen you for ages etc.

Recognising certain grammar structures as lexical

items means that they can be introduced much earlier,

without structural analysis or elaboration. Indeed, since the

concept of notions and functions made its way into language

teaching, particularly as Communicative Language Teaching

(CLT) gained prominence, some structures associated with

grammar started to be taught lexically (or functionally). I’d like

to is not taught as ‹the conditional› but as a chunk expressing

desire. Similarly many other ‹traditional› grammar items can

be introduced lexically relatively early on.

Less grammar or more grammar?

You are, no doubt, all familiar with students who on one hand seem to know the ‘rules’ of grammar but still fail to produce grammatically correct sentences when speaking or, on the other, sound unnatural and foreign-like even when their sentences are grammatically correct. Michael Lewis, who might be considered the founder of the Lexical Approach, once claimed that there was no direct relationship between the knowledge of grammar and speaking. In contrast, the knowledge of formulaic language has been shown by research to have a significant bearing on the natural language production.

Furthermore, certain grammar rules are practically impossible to learn. Dave Willis cites the grammar of orientation (which includes the notoriously difficult present perfect and the uses of certain modal verbs) as particularly resistant to teaching. The only way to grasp their meaning is through continuous exposure and use.

Finally, even the most authoritative English grammars never claim to provide a comprehensive description of all the grammar, hence the word ‘introduction’ often used in their titles (for instance, Huddleston & Pullum’s A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar or Halliday’s An Introduction to Functional Grammar).

If grammarians do not even attempt to address all areas of grammar, how can we, practitioners, cover all the aspects of grammar in our teaching, especially if all we seem to focus on is a limited selection of discrete items, comprised mostly of tenses and a handful of modal verbs? It would seem that we need to expose our students to a lot of naturally occurring language and frequently draw their attention to various grammar points as they arise.

For example, while teaching the expression fall asleep / be asleep you can ask your students:

• Don’t make any noise – she’s fallen asleep.

• Don’t make any noise – she’s asleep.

What does’s stand for in each of these cases (is or has)?

One of the fathers of the Communicative Language Teaching Henry Widdowson advocated using lexical items as a starting point and then ‘showing how they need to be grammatically modified to be communicatively effective’ (1990:95). For example, when exploring a text with your students, you may come across a sentence like this:

• They’ve been married for seven years.

You can ask your students: When did they get married? How should you change the sentence if the couple you are talking about is no longer married?

The above demonstrates how the teacher should be constantly on the ball and take every opportunity to draw students’ attention to grammar. Such short but frequent ‘grammar spots’ will help to slowly raise students’ awareness and build their understanding of the English grammar system.

[…]

Conclusion

So is there room for grammar instruction in the classroom? Certainly yes. But the grammar practice should always start with the exploitation of lexical items. Exposing students to a lot of natural and contextualised examples will offer a lexical way into the grammar of the language.

To sum up, grammar should play some role in language teaching but should not occupy a big part of class time. Instead grammar should be delivered in small but frequent portions. Students should be encouraged to collect a lot of examples of a particular structure before being invited to analyse it. Hence, analysis should be preceded by synthesis.

Lastly, language practitioners should bear in mind that grammar acquisition is an incremental process which requires frequent focus and refocus on the items already studied.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professionaldevelopment/teachers/knowing-subject/articles/grammar-vs-lexisor-grammar-through. Accessed on: April 29, 2024.

Read the following text to answer the question.

By Leo Selivan

In this article, informed by the Lexical Approach, I reflect on grammar instruction in the classroom […]. I consider the problems with ‘traditional’ grammar teaching before arguing that what we actually need is more grammar input as well as showing how lexis can provide necessary ‘crutches’ for the learner.

Lexis = vocabulary + grammar

The shift in ELT from grammar to lexis mirrors a similar change in the attitude of linguists. In the past linguists were preoccupied with the grammar of language; however the advances in corpus linguistics have pushed lexis to the forefront. The term ‘lexis’, which was traditionally used by linguists, is a common word these days and frequently used even in textbooks.

Why use a technical term borrowed from the realm of linguistics instead of the word ‘vocabulary’? Quite simply because vocabulary is typically seen as individual words (often presented in lists) whereas lexis is a somewhat wider concept and consists of collocations, chunks and formulaic expressions. It also includes certain patterns that were traditionally associated with the grammar of a language, e.g. If I were you…, I haven’t seen you for ages etc.

Recognising certain grammar structures as lexical

items means that they can be introduced much earlier,

without structural analysis or elaboration. Indeed, since the

concept of notions and functions made its way into language

teaching, particularly as Communicative Language Teaching

(CLT) gained prominence, some structures associated with

grammar started to be taught lexically (or functionally). I’d like

to is not taught as ‹the conditional› but as a chunk expressing

desire. Similarly many other ‹traditional› grammar items can

be introduced lexically relatively early on.

Less grammar or more grammar?

You are, no doubt, all familiar with students who on one hand seem to know the ‘rules’ of grammar but still fail to produce grammatically correct sentences when speaking or, on the other, sound unnatural and foreign-like even when their sentences are grammatically correct. Michael Lewis, who might be considered the founder of the Lexical Approach, once claimed that there was no direct relationship between the knowledge of grammar and speaking. In contrast, the knowledge of formulaic language has been shown by research to have a significant bearing on the natural language production.

Furthermore, certain grammar rules are practically impossible to learn. Dave Willis cites the grammar of orientation (which includes the notoriously difficult present perfect and the uses of certain modal verbs) as particularly resistant to teaching. The only way to grasp their meaning is through continuous exposure and use.

Finally, even the most authoritative English grammars never claim to provide a comprehensive description of all the grammar, hence the word ‘introduction’ often used in their titles (for instance, Huddleston & Pullum’s A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar or Halliday’s An Introduction to Functional Grammar).

If grammarians do not even attempt to address all areas of grammar, how can we, practitioners, cover all the aspects of grammar in our teaching, especially if all we seem to focus on is a limited selection of discrete items, comprised mostly of tenses and a handful of modal verbs? It would seem that we need to expose our students to a lot of naturally occurring language and frequently draw their attention to various grammar points as they arise.

For example, while teaching the expression fall asleep / be asleep you can ask your students:

• Don’t make any noise – she’s fallen asleep.

• Don’t make any noise – she’s asleep.

What does’s stand for in each of these cases (is or has)?

One of the fathers of the Communicative Language Teaching Henry Widdowson advocated using lexical items as a starting point and then ‘showing how they need to be grammatically modified to be communicatively effective’ (1990:95). For example, when exploring a text with your students, you may come across a sentence like this:

• They’ve been married for seven years.

You can ask your students: When did they get married? How should you change the sentence if the couple you are talking about is no longer married?

The above demonstrates how the teacher should be constantly on the ball and take every opportunity to draw students’ attention to grammar. Such short but frequent ‘grammar spots’ will help to slowly raise students’ awareness and build their understanding of the English grammar system.

[…]

Conclusion

So is there room for grammar instruction in the classroom? Certainly yes. But the grammar practice should always start with the exploitation of lexical items. Exposing students to a lot of natural and contextualised examples will offer a lexical way into the grammar of the language.

To sum up, grammar should play some role in language teaching but should not occupy a big part of class time. Instead grammar should be delivered in small but frequent portions. Students should be encouraged to collect a lot of examples of a particular structure before being invited to analyse it. Hence, analysis should be preceded by synthesis.

Lastly, language practitioners should bear in mind that grammar acquisition is an incremental process which requires frequent focus and refocus on the items already studied.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professionaldevelopment/teachers/knowing-subject/articles/grammar-vs-lexisor-grammar-through. Accessed on: April 29, 2024.

Read the following text to answer the question.

By Leo Selivan

In this article, informed by the Lexical Approach, I reflect on grammar instruction in the classroom […]. I consider the problems with ‘traditional’ grammar teaching before arguing that what we actually need is more grammar input as well as showing how lexis can provide necessary ‘crutches’ for the learner.

Lexis = vocabulary + grammar

The shift in ELT from grammar to lexis mirrors a similar change in the attitude of linguists. In the past linguists were preoccupied with the grammar of language; however the advances in corpus linguistics have pushed lexis to the forefront. The term ‘lexis’, which was traditionally used by linguists, is a common word these days and frequently used even in textbooks.

Why use a technical term borrowed from the realm of linguistics instead of the word ‘vocabulary’? Quite simply because vocabulary is typically seen as individual words (often presented in lists) whereas lexis is a somewhat wider concept and consists of collocations, chunks and formulaic expressions. It also includes certain patterns that were traditionally associated with the grammar of a language, e.g. If I were you…, I haven’t seen you for ages etc.

Recognising certain grammar structures as lexical

items means that they can be introduced much earlier,

without structural analysis or elaboration. Indeed, since the

concept of notions and functions made its way into language

teaching, particularly as Communicative Language Teaching

(CLT) gained prominence, some structures associated with

grammar started to be taught lexically (or functionally). I’d like

to is not taught as ‹the conditional› but as a chunk expressing

desire. Similarly many other ‹traditional› grammar items can

be introduced lexically relatively early on.

Less grammar or more grammar?

You are, no doubt, all familiar with students who on one hand seem to know the ‘rules’ of grammar but still fail to produce grammatically correct sentences when speaking or, on the other, sound unnatural and foreign-like even when their sentences are grammatically correct. Michael Lewis, who might be considered the founder of the Lexical Approach, once claimed that there was no direct relationship between the knowledge of grammar and speaking. In contrast, the knowledge of formulaic language has been shown by research to have a significant bearing on the natural language production.

Furthermore, certain grammar rules are practically impossible to learn. Dave Willis cites the grammar of orientation (which includes the notoriously difficult present perfect and the uses of certain modal verbs) as particularly resistant to teaching. The only way to grasp their meaning is through continuous exposure and use.

Finally, even the most authoritative English grammars never claim to provide a comprehensive description of all the grammar, hence the word ‘introduction’ often used in their titles (for instance, Huddleston & Pullum’s A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar or Halliday’s An Introduction to Functional Grammar).

If grammarians do not even attempt to address all areas of grammar, how can we, practitioners, cover all the aspects of grammar in our teaching, especially if all we seem to focus on is a limited selection of discrete items, comprised mostly of tenses and a handful of modal verbs? It would seem that we need to expose our students to a lot of naturally occurring language and frequently draw their attention to various grammar points as they arise.

For example, while teaching the expression fall asleep / be asleep you can ask your students:

• Don’t make any noise – she’s fallen asleep.

• Don’t make any noise – she’s asleep.

What does’s stand for in each of these cases (is or has)?

One of the fathers of the Communicative Language Teaching Henry Widdowson advocated using lexical items as a starting point and then ‘showing how they need to be grammatically modified to be communicatively effective’ (1990:95). For example, when exploring a text with your students, you may come across a sentence like this:

• They’ve been married for seven years.

You can ask your students: When did they get married? How should you change the sentence if the couple you are talking about is no longer married?

The above demonstrates how the teacher should be constantly on the ball and take every opportunity to draw students’ attention to grammar. Such short but frequent ‘grammar spots’ will help to slowly raise students’ awareness and build their understanding of the English grammar system.

[…]

Conclusion

So is there room for grammar instruction in the classroom? Certainly yes. But the grammar practice should always start with the exploitation of lexical items. Exposing students to a lot of natural and contextualised examples will offer a lexical way into the grammar of the language.

To sum up, grammar should play some role in language teaching but should not occupy a big part of class time. Instead grammar should be delivered in small but frequent portions. Students should be encouraged to collect a lot of examples of a particular structure before being invited to analyse it. Hence, analysis should be preceded by synthesis.

Lastly, language practitioners should bear in mind that grammar acquisition is an incremental process which requires frequent focus and refocus on the items already studied.

Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professionaldevelopment/teachers/knowing-subject/articles/grammar-vs-lexisor-grammar-through. Accessed on: April 29, 2024.

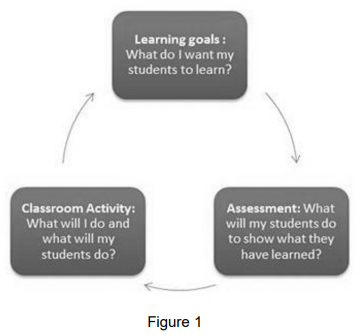

Empowering language learning through assessment

Assessment of, as, and for learning

Empowering language learning through assessment

Assessment of, as, and for learning

The word reliability is closest in meaning to

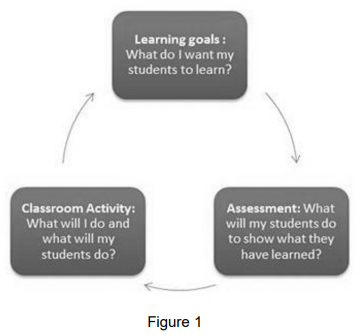

Empowering language learning through assessment

Assessment of, as, and for learning

Empowering language learning through assessment

Assessment of, as, and for learning

Empowering language learning through assessment

Assessment of, as, and for learning