Questões de Concurso

Para engenheiro florestal

Foram encontradas 3.298 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Se o olho não vê o bolso não sente

O ser humano é um animal cooperativo por natureza. Mas em todas as sociedades a desigualdade corre solta. Alguns acabam mais ricos que outros. Faz séculos que os cientistas tentam descobrir os comportamentos que provocam a desigualdade. Uma nova rota de investigação consiste em usar jogos cuidadosamente desenhados para observar o comportamento do ser humano durante sua interação social. Em um novo experimento, os cientistas demonstraram que o simples fato de um indivíduo observar a desigualdade existente no grupo induz comportamentos que aumentam a desigualdade. [...]

A conclusão é que nosso comportamento provoca a desigualdade mesmo quando as pessoas partem de uma situação de total igualdade. Mas, quando a desigualdade já existe, ela tende a aumentar rapidamente quando podemos nos comparar com os demais. Em suma, inveja e exibicionismo provocam comportamentos que aumentam a desigualdade entre os homens. Como diria minha avó: grande novidade.

(Fernando Reinach. O Estado de S. Paulo. Metrópole, 24.10.2015. Adaptado)

A conspiração dos imbecis

O Castelo Sforzesco, em Milão, preserva tesouros da arte italiana, como a Pietà Rondanini, de Michelangelo. Um dos sóbrios edifícios residenciais em frente ao castelo abriga outro tesouro italiano: Umberto Eco, filósofo, crítico literário e romancista traduzido em mais de quarenta idiomas. O autor de O Nome da Rosa, romance ambientado na Idade Média que vendeu mais de 30 milhões de exemplares, lançou neste ano Número Zero – que chega ao Brasil nesta semana, pela Record –, um retrato crítico do jornalismo subordinado a interesses políticos. Na casa milanesa, onde conserva uma biblioteca de 30000 livros (há outros 20000 em sua residência em Urbino), Eco, 83 anos, recebeu VEJA para falar de jornalismo, internet, conspirações e, claro, literatura.

VEJA: Foi um estrondo a sua declaração, em uma cerimônia na Universidade de Torino, de que a internet dá voz a uma multidão de imbecis. O que o senhor achou da dimensão que o assunto tomou?

ECO: As pessoas fizeram um grande estardalhaço por eu ter dito que multidões de imbecis têm agora como divulgar suas opiniões. Ora, veja bem, num mundo com mais de 7 bilhões de pessoas, você não concordaria que há muitos imbecis? Não estou falando ofensivamente quanto ao caráter das pessoas. O sujeito pode ser um excelente funcionário ou pai de família, mas ser um completo imbecil em diversos assuntos. Com a internet e as redes sociais, o imbecil passa a opinar a respeito de temas que não entende.

VEJA: Mas a internet tem seu valor, não?

ECO: A internet é como Funes, o memorioso, o personagem de Jorge Luis Borges: lembra tudo, não esquece nada. É preciso filtrar, distinguir. Sempre digo que a primeira disciplina a ser ministrada nas escolas deveria ser sobre como usar a internet: como analisar informações. O problema é que nem mesmo os professores estão preparados para isso. Foi nesse sentido que defendi recentemente que os jornais, em vez de se tornar vítimas da internet, repetindo o que circula na rede, deveriam dedicar espaço para a análise das informações que circulam nos sites, mostrando aos leitores o que é sério, o que é fraude.

(Eduardo Wolf. Disponível em http://veja.abril.com.br. Acesso em 07.07.2015. Adaptado)

A conspiração dos imbecis

O Castelo Sforzesco, em Milão, preserva tesouros da arte italiana, como a Pietà Rondanini, de Michelangelo. Um dos sóbrios edifícios residenciais em frente ao castelo abriga outro tesouro italiano: Umberto Eco, filósofo, crítico literário e romancista traduzido em mais de quarenta idiomas. O autor de O Nome da Rosa, romance ambientado na Idade Média que vendeu mais de 30 milhões de exemplares, lançou neste ano Número Zero – que chega ao Brasil nesta semana, pela Record –, um retrato crítico do jornalismo subordinado a interesses políticos. Na casa milanesa, onde conserva uma biblioteca de 30000 livros (há outros 20000 em sua residência em Urbino), Eco, 83 anos, recebeu VEJA para falar de jornalismo, internet, conspirações e, claro, literatura.

VEJA: Foi um estrondo a sua declaração, em uma cerimônia na Universidade de Torino, de que a internet dá voz a uma multidão de imbecis. O que o senhor achou da dimensão que o assunto tomou?

ECO: As pessoas fizeram um grande estardalhaço por eu ter dito que multidões de imbecis têm agora como divulgar suas opiniões. Ora, veja bem, num mundo com mais de 7 bilhões de pessoas, você não concordaria que há muitos imbecis? Não estou falando ofensivamente quanto ao caráter das pessoas. O sujeito pode ser um excelente funcionário ou pai de família, mas ser um completo imbecil em diversos assuntos. Com a internet e as redes sociais, o imbecil passa a opinar a respeito de temas que não entende.

VEJA: Mas a internet tem seu valor, não?

ECO: A internet é como Funes, o memorioso, o personagem de Jorge Luis Borges: lembra tudo, não esquece nada. É preciso filtrar, distinguir. Sempre digo que a primeira disciplina a ser ministrada nas escolas deveria ser sobre como usar a internet: como analisar informações. O problema é que nem mesmo os professores estão preparados para isso. Foi nesse sentido que defendi recentemente que os jornais, em vez de se tornar vítimas da internet, repetindo o que circula na rede, deveriam dedicar espaço para a análise das informações que circulam nos sites, mostrando aos leitores o que é sério, o que é fraude.

(Eduardo Wolf. Disponível em http://veja.abril.com.br. Acesso em 07.07.2015. Adaptado)

A conspiração dos imbecis

O Castelo Sforzesco, em Milão, preserva tesouros da arte italiana, como a Pietà Rondanini, de Michelangelo. Um dos sóbrios edifícios residenciais em frente ao castelo abriga outro tesouro italiano: Umberto Eco, filósofo, crítico literário e romancista traduzido em mais de quarenta idiomas. O autor de O Nome da Rosa, romance ambientado na Idade Média que vendeu mais de 30 milhões de exemplares, lançou neste ano Número Zero – que chega ao Brasil nesta semana, pela Record –, um retrato crítico do jornalismo subordinado a interesses políticos. Na casa milanesa, onde conserva uma biblioteca de 30000 livros (há outros 20000 em sua residência em Urbino), Eco, 83 anos, recebeu VEJA para falar de jornalismo, internet, conspirações e, claro, literatura.

VEJA: Foi um estrondo a sua declaração, em uma cerimônia na Universidade de Torino, de que a internet dá voz a uma multidão de imbecis. O que o senhor achou da dimensão que o assunto tomou?

ECO: As pessoas fizeram um grande estardalhaço por eu ter dito que multidões de imbecis têm agora como divulgar suas opiniões. Ora, veja bem, num mundo com mais de 7 bilhões de pessoas, você não concordaria que há muitos imbecis? Não estou falando ofensivamente quanto ao caráter das pessoas. O sujeito pode ser um excelente funcionário ou pai de família, mas ser um completo imbecil em diversos assuntos. Com a internet e as redes sociais, o imbecil passa a opinar a respeito de temas que não entende.

VEJA: Mas a internet tem seu valor, não?

ECO: A internet é como Funes, o memorioso, o personagem de Jorge Luis Borges: lembra tudo, não esquece nada. É preciso filtrar, distinguir. Sempre digo que a primeira disciplina a ser ministrada nas escolas deveria ser sobre como usar a internet: como analisar informações. O problema é que nem mesmo os professores estão preparados para isso. Foi nesse sentido que defendi recentemente que os jornais, em vez de se tornar vítimas da internet, repetindo o que circula na rede, deveriam dedicar espaço para a análise das informações que circulam nos sites, mostrando aos leitores o que é sério, o que é fraude.

(Eduardo Wolf. Disponível em http://veja.abril.com.br. Acesso em 07.07.2015. Adaptado)

Sabe-se que as notas de uma prova têm distribuição Normal com média μ = 6,5 e variância σ2 = 4 . Adicionalmente, são conhecidos alguns valores tabulados da normal-padrão.

Φ(1,3 ) ≅ 0,90 Φ(1,65) ≅ 0,95 Φ(1,95 ) ≅ 0,975

Onde,

Φ(z) é a função distribuição acumulada da Normal Padrão.

Considerando-se que apenas os 10% que atinjam as maiores notas serão aprovados, a nota mínima para aprovação é:

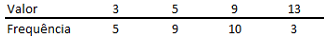

Após a extração de uma amostra, as observações obtidas são tabuladas, gerando a seguinte distribuição de frequências:

Considerando que E(X) = Média de X, Mo(X) = Moda de X e Me(X)

= Mediana de X, é correto afirmar que:

Sobre os amigos Marcos, Renato e Waldo, sabe-se que:

I - Se Waldo é flamenguista, então Marcos não é tricolor;

II - Se Renato não é vascaíno, então Marcos é tricolor;

III - Se Renato é vascaíno, então Waldo não é flamenguista.

Logo, deduz-se que:

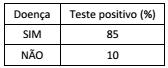

De um grupo de controle para o acompanhamento de uma determinada doença, 4% realmente têm a doença. A tabela a seguir mostra as porcentagens das pessoas que têm e das que não têm a doença e que apresentaram resultado positivo em um determinado teste.

Entre as pessoas desse grupo que apresentaram resultado

positivo no teste, a porcentagem daquelas que realmente têm a

doença é aproximadamente:

Em uma caixa há doze dúzias de laranjas, sobre as quais sabe-se que:

I - há pelo menos duas laranjas estragadas;

II - dadas seis quaisquer dessas laranjas, há pelo menos duas não estragadas.

Sobre essas doze dúzias de laranjas, deduz-se que:

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT I

Will computers ever truly understand what we’re saying?

Date: January 11, 2016

Source University of California - Berkeley

Summary:

If you think computers are quickly approaching true human communication, think again. Computers like Siri often get confused because they judge meaning by looking at a word’s statistical regularity. This is unlike humans, for whom context is more important than the word or signal, according to a researcher who invented a communication game allowing only nonverbal cues, and used it to pinpoint regions of the brain where mutual understanding takes place.

From Apple’s Siri to Honda’s robot Asimo, machines seem to be getting better and better at communicating with humans. But some neuroscientists caution that today’s computers will never truly understand what we’re saying because they do not take into account the context of a conversation the way people do.

Specifically, say University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral fellow Arjen Stolk and his Dutch colleagues, machines don’t develop a shared understanding of the people, place and situation - often including a long social history - that is key to human communication. Without such common ground, a computer cannot help but be confused.

“People tend to think of communication as an exchange of linguistic signs or gestures, forgetting that much of communication is about the social context, about who you are communicating with,” Stolk said.

The word “bank,” for example, would be interpreted one way if you’re holding a credit card but a different way if you’re holding a fishing pole. Without context, making a “V” with two fingers could mean victory, the number two, or “these are the two fingers I broke.”

“All these subtleties are quite crucial to understanding one another,” Stolk said, perhaps more so than the words and signals that computers and many neuroscientists focus on as the key to communication. “In fact, we can understand one another without language, without words and signs that already have a shared meaning.”

(Adapted from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/1 60111135231.htm)

TEXT I

Will computers ever truly understand what we’re saying?

Date: January 11, 2016

Source University of California - Berkeley

Summary:

If you think computers are quickly approaching true human communication, think again. Computers like Siri often get confused because they judge meaning by looking at a word’s statistical regularity. This is unlike humans, for whom context is more important than the word or signal, according to a researcher who invented a communication game allowing only nonverbal cues, and used it to pinpoint regions of the brain where mutual understanding takes place.

From Apple’s Siri to Honda’s robot Asimo, machines seem to be getting better and better at communicating with humans. But some neuroscientists caution that today’s computers will never truly understand what we’re saying because they do not take into account the context of a conversation the way people do.

Specifically, say University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral fellow Arjen Stolk and his Dutch colleagues, machines don’t develop a shared understanding of the people, place and situation - often including a long social history - that is key to human communication. Without such common ground, a computer cannot help but be confused.

“People tend to think of communication as an exchange of linguistic signs or gestures, forgetting that much of communication is about the social context, about who you are communicating with,” Stolk said.

The word “bank,” for example, would be interpreted one way if you’re holding a credit card but a different way if you’re holding a fishing pole. Without context, making a “V” with two fingers could mean victory, the number two, or “these are the two fingers I broke.”

“All these subtleties are quite crucial to understanding one another,” Stolk said, perhaps more so than the words and signals that computers and many neuroscientists focus on as the key to communication. “In fact, we can understand one another without language, without words and signs that already have a shared meaning.”

(Adapted from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/1 60111135231.htm)

TEXT I

Will computers ever truly understand what we’re saying?

Date: January 11, 2016

Source University of California - Berkeley

Summary:

If you think computers are quickly approaching true human communication, think again. Computers like Siri often get confused because they judge meaning by looking at a word’s statistical regularity. This is unlike humans, for whom context is more important than the word or signal, according to a researcher who invented a communication game allowing only nonverbal cues, and used it to pinpoint regions of the brain where mutual understanding takes place.

From Apple’s Siri to Honda’s robot Asimo, machines seem to be getting better and better at communicating with humans. But some neuroscientists caution that today’s computers will never truly understand what we’re saying because they do not take into account the context of a conversation the way people do.

Specifically, say University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral fellow Arjen Stolk and his Dutch colleagues, machines don’t develop a shared understanding of the people, place and situation - often including a long social history - that is key to human communication. Without such common ground, a computer cannot help but be confused.

“People tend to think of communication as an exchange of linguistic signs or gestures, forgetting that much of communication is about the social context, about who you are communicating with,” Stolk said.

The word “bank,” for example, would be interpreted one way if you’re holding a credit card but a different way if you’re holding a fishing pole. Without context, making a “V” with two fingers could mean victory, the number two, or “these are the two fingers I broke.”

“All these subtleties are quite crucial to understanding one another,” Stolk said, perhaps more so than the words and signals that computers and many neuroscientists focus on as the key to communication. “In fact, we can understand one another without language, without words and signs that already have a shared meaning.”

(Adapted from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/1 60111135231.htm)