Questões de Vestibular

Comentadas sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 680 questões

Pseudoscientific claims that music helps plants grow have been made for decades, despite evidence that is shaky at best. Yet new research suggests some flora may be capable of sensing sounds, such as the gurgle of water through a pipe or the buzzing of insects.

In a recent study, Monica Gagliano, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia, and her colleagues placed pea seedlings in pots shaped like an upside-down Y. One arm of each pot was placed in either a tray of water or a coiled plastic tube through which water flowed; the other arm had dry soil. The roots grew toward the arm of the pipe with the fluid, regardless of whether it was easily accessible or hidden inside the tubing. “They just knew the water was there, even if the only thing to detect was the sound of it flowing inside the pipe,” Gagliano says. Yet when the seedlings were given a choice between the water tube and some moistened soil, their roots favored the latter. She hypothesizes that these plants use sound waves to detect water at a distance but follow moisture gradients to home in on their target when it is closer.

The research, reported earlier this year in Oecologia, is not the first to suggest flora can detect and interpret sounds. A 2014 study showed the rock cress Arabidopsis can distinguish between caterpillar chewing sounds and wind vibrations – the plant produced more chemical toxins after “hearing” a recording of feeding insects. “We tend to underestimate plants because their responses are usually less visible to us. But leaves turn out to be extremely sensitive vibration detectors,” says lead study author Heidi M. Appel, an environmental scientist now at the University of Toledo.

Pseudoscientific claims that music helps plants grow have been made for decades, despite evidence that is shaky at best. Yet new research suggests some flora may be capable of sensing sounds, such as the gurgle of water through a pipe or the buzzing of insects.

In a recent study, Monica Gagliano, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia, and her colleagues placed pea seedlings in pots shaped like an upside-down Y. One arm of each pot was placed in either a tray of water or a coiled plastic tube through which water flowed; the other arm had dry soil. The roots grew toward the arm of the pipe with the fluid, regardless of whether it was easily accessible or hidden inside the tubing. “They just knew the water was there, even if the only thing to detect was the sound of it flowing inside the pipe,” Gagliano says. Yet when the seedlings were given a choice between the water tube and some moistened soil, their roots favored the latter. She hypothesizes that these plants use sound waves to detect water at a distance but follow moisture gradients to home in on their target when it is closer.

The research, reported earlier this year in Oecologia, is not the first to suggest flora can detect and interpret sounds. A 2014 study showed the rock cress Arabidopsis can distinguish between caterpillar chewing sounds and wind vibrations – the plant produced more chemical toxins after “hearing” a recording of feeding insects. “We tend to underestimate plants because their responses are usually less visible to us. But leaves turn out to be extremely sensitive vibration detectors,” says lead study author Heidi M. Appel, an environmental scientist now at the University of Toledo.

Pseudoscientific claims that music helps plants grow have been made for decades, despite evidence that is shaky at best. Yet new research suggests some flora may be capable of sensing sounds, such as the gurgle of water through a pipe or the buzzing of insects.

In a recent study, Monica Gagliano, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia, and her colleagues placed pea seedlings in pots shaped like an upside-down Y. One arm of each pot was placed in either a tray of water or a coiled plastic tube through which water flowed; the other arm had dry soil. The roots grew toward the arm of the pipe with the fluid, regardless of whether it was easily accessible or hidden inside the tubing. “They just knew the water was there, even if the only thing to detect was the sound of it flowing inside the pipe,” Gagliano says. Yet when the seedlings were given a choice between the water tube and some moistened soil, their roots favored the latter. She hypothesizes that these plants use sound waves to detect water at a distance but follow moisture gradients to home in on their target when it is closer.

The research, reported earlier this year in Oecologia, is not the first to suggest flora can detect and interpret sounds. A 2014 study showed the rock cress Arabidopsis can distinguish between caterpillar chewing sounds and wind vibrations – the plant produced more chemical toxins after “hearing” a recording of feeding insects. “We tend to underestimate plants because their responses are usually less visible to us. But leaves turn out to be extremely sensitive vibration detectors,” says lead study author Heidi M. Appel, an environmental scientist now at the University of Toledo.

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller’s relationship with music. As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction. This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played. He describes his unusual musical talent as “downloading” music into his head. His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would “suddenly pop up and say: ‘I’ve got a symphony’”. Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

“I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube,” he remembers. “It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind. I could then just play it on the piano – all without being taught.”

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels “very much aware” of how different his approach is to music – symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child. This, his mother says, came as a “surprise to the family and myself – I’d never listened to classical music in my life”.

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works. Describing this process as “making music with my mind”, Michael says composing classical symphonies “helps me to express myself through music – it makes me calm”. Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist. He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says “write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians – then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition”. Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

(Alex Taylor. www.bbc.com, 27.03.2018. Adaptado.)

Disponível em: <https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/26963-if-you-can-t-flythen-run-if-you-can-t-run>. Acesso em: set. 2018.

Disponível em: <https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/26963-if-you-can-t-flythen-run-if-you-can-t-run>. Acesso em: set. 2018.According to this quote by Martin Luther King Jr.

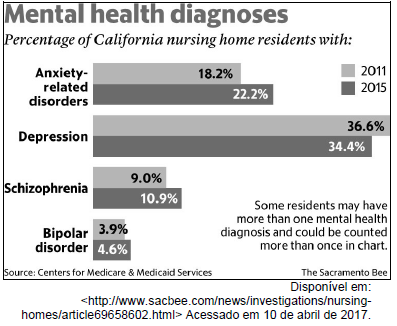

Read the demographics below and answer the following question based on it.

As regards the California nursing home residents

demographics above it is true to state that

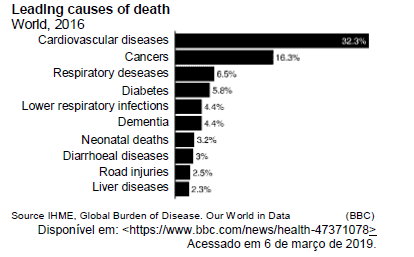

According to the graph above we can assert that

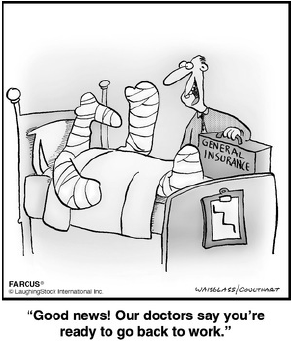

Read the comic strip below and answer the following question based on it.

Disponível em:<http://www.docjokes.com/i/farcus-comic-strip-on-gocomics-com.html> Acessado em 25 de abril de 2016.

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

(Claire Marshall. www.bbc.com, 15.05.2019. Adaptado.)