Questões de Vestibular

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 4.863 questões

T E X T

Can you learn in your sleep?

Sleep is known to be crucial for learning and memory formation. What's more, scientists have even managed to pick out specific memories and consolidate them during sleep. However, the exact mechanisms behind this were unknown — until now.

Those among us who grew up with the popular cartoon "Dexter's Laboratory" might remember the famous episode wherein Dexter's trying to learn French overnight. He creates a device that helps him to learn in his sleep by playing French phrases to him. Of course, since the show is a comedy, Dexter's record gets stuck on the phrase "Omelette du fromage" and the next day he's incapable of saying anything else. This is, of course, a problem that puts him through a series of hilarious situations.

The idea that we can learn in our sleep has captivated the minds of artists and scientists alike; the possibility that one day we could all drastically improve our productivity by learning in our sleep is very appealing. But could such a scenario ever become a reality?

New research seems to suggest so, and scientists in general are moving closer to understanding precisely what goes on in the brain when we sleep and how the restful state affects learning and memory formation.

For instance, previous studies have shown that non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep — or dreamless sleep — is crucial for consolidating memories. It has also been shown that sleep spindles, or sudden spikes in oscillatory brain activity that can be seen on an electroencephalogram (EEG) during the second stage of non-REM sleep, are key for this memory consolidation. Scientists were also able to specifically target certain memories and reactivate, or strengthen, them by using auditory cues.

However, the mechanism behind such achievements remained mysterious until now. Researchers were also unaware if such mechanisms would help with memorizing new information.

Therefore, a team of researchers set out to investigate. Scott Cairney, from the University of York in the United Kingdom, co-led the research with Bernhard Staresina, who works at the University of Birmingham, also in the U.K. Their findings were published in the journal Current Biology.

Cairney explains the motivation for the research, saying, "We are quite certain that memories are reactivated in the brain during sleep, but we don't know the neural processes that underpin this phenomenon." "Sleep spindles," he continues, "have been linked to the benefits of sleep for memory in previous research, so we wanted to investigate whether these brain waves mediate reactivation. If they support memory reactivation, we further reasoned that it could be possible to decipher memory signals at the time that these spindles took place."

To test their hypotheses, Cairney and his colleagues asked 46 participants "to learn associations between words and pictures of objects or scenes before a nap." Afterward, some of the participants took a 90-minute nap, whereas others stayed awake. To those who napped, "Half of the words were [...] replayed during the nap to trigger the reactivation of the newly learned picture memories," explains Cairney.

"When the participants woke after a good period of sleep," he says, "we presented them again with the words and asked them to recall the object and scene pictures. We found that their memory was better for the pictures that were connected to the words that were presented in sleep, compared to those words that weren't," Cairney reports.

Using an EEG machine, the researchers were also able to see that playing the associated words to reactivate memories triggered sleep spindles in the participants' brains. More specifically, the EEG sleep spindle patterns "told" the researchers whether the participants were processing memories related to objects or memories related to scenes.

"Our data suggest that spindles facilitate processing of relevant memory features during sleep and that this process boosts memory consolidation," says Staresina. "While it has been shown previously," he continues, "that targeted memory reactivation can boost memory consolidation during sleep, we now show that sleep spindles might represent the key underlying mechanism."

Cairney adds, "When you are awake you learn new things, but when you are asleep you refine them, making it easier to retrieve them and apply them correctly when you need them the most. This is important for how we learn but also for how we might help retain healthy brain functions."

Staresina suggests that this newly gained knowledge could lead to effective strategies for boosting memory while sleeping.

So, though learning things from scratch à la "Dexter's Lab" may take a while to become a reality, we can safely say that our brains continue to learn while we sleep, and that researchers just got a lot closer to understanding why this happens.

From:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/Mar/2018

T E X T

Can you learn in your sleep?

Sleep is known to be crucial for learning and memory formation. What's more, scientists have even managed to pick out specific memories and consolidate them during sleep. However, the exact mechanisms behind this were unknown — until now.

Those among us who grew up with the popular cartoon "Dexter's Laboratory" might remember the famous episode wherein Dexter's trying to learn French overnight. He creates a device that helps him to learn in his sleep by playing French phrases to him. Of course, since the show is a comedy, Dexter's record gets stuck on the phrase "Omelette du fromage" and the next day he's incapable of saying anything else. This is, of course, a problem that puts him through a series of hilarious situations.

The idea that we can learn in our sleep has captivated the minds of artists and scientists alike; the possibility that one day we could all drastically improve our productivity by learning in our sleep is very appealing. But could such a scenario ever become a reality?

New research seems to suggest so, and scientists in general are moving closer to understanding precisely what goes on in the brain when we sleep and how the restful state affects learning and memory formation.

For instance, previous studies have shown that non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep — or dreamless sleep — is crucial for consolidating memories. It has also been shown that sleep spindles, or sudden spikes in oscillatory brain activity that can be seen on an electroencephalogram (EEG) during the second stage of non-REM sleep, are key for this memory consolidation. Scientists were also able to specifically target certain memories and reactivate, or strengthen, them by using auditory cues.

However, the mechanism behind such achievements remained mysterious until now. Researchers were also unaware if such mechanisms would help with memorizing new information.

Therefore, a team of researchers set out to investigate. Scott Cairney, from the University of York in the United Kingdom, co-led the research with Bernhard Staresina, who works at the University of Birmingham, also in the U.K. Their findings were published in the journal Current Biology.

Cairney explains the motivation for the research, saying, "We are quite certain that memories are reactivated in the brain during sleep, but we don't know the neural processes that underpin this phenomenon." "Sleep spindles," he continues, "have been linked to the benefits of sleep for memory in previous research, so we wanted to investigate whether these brain waves mediate reactivation. If they support memory reactivation, we further reasoned that it could be possible to decipher memory signals at the time that these spindles took place."

To test their hypotheses, Cairney and his colleagues asked 46 participants "to learn associations between words and pictures of objects or scenes before a nap." Afterward, some of the participants took a 90-minute nap, whereas others stayed awake. To those who napped, "Half of the words were [...] replayed during the nap to trigger the reactivation of the newly learned picture memories," explains Cairney.

"When the participants woke after a good period of sleep," he says, "we presented them again with the words and asked them to recall the object and scene pictures. We found that their memory was better for the pictures that were connected to the words that were presented in sleep, compared to those words that weren't," Cairney reports.

Using an EEG machine, the researchers were also able to see that playing the associated words to reactivate memories triggered sleep spindles in the participants' brains. More specifically, the EEG sleep spindle patterns "told" the researchers whether the participants were processing memories related to objects or memories related to scenes.

"Our data suggest that spindles facilitate processing of relevant memory features during sleep and that this process boosts memory consolidation," says Staresina. "While it has been shown previously," he continues, "that targeted memory reactivation can boost memory consolidation during sleep, we now show that sleep spindles might represent the key underlying mechanism."

Cairney adds, "When you are awake you learn new things, but when you are asleep you refine them, making it easier to retrieve them and apply them correctly when you need them the most. This is important for how we learn but also for how we might help retain healthy brain functions."

Staresina suggests that this newly gained knowledge could lead to effective strategies for boosting memory while sleeping.

So, though learning things from scratch à la "Dexter's Lab" may take a while to become a reality, we can safely say that our brains continue to learn while we sleep, and that researchers just got a lot closer to understanding why this happens.

From:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/Mar/2018

What time isit? Thatsimple question probably is asked more often today than ever. In our clock‐studded, cell‐phone society, the answer is never more than a glance away, and so we can blissfully partition our daysinto eversmaller incrementsfor ever more tightly scheduled tasks, confident that we will always know it is 7:03 P.M.

Modern scientific revelations about time, however, make the question endlessly frustrating. If we seek a precise knowledge of the time, the elusive infinitesimal of “now” dissolves into a scattering flock of nanoseconds. Bound by the speed of light and the velocity of nerve impulses, our perceptions of the present sketch the world as it was an instant ago—for all that our consciousness pretends otherwise, we can never catch up.

Even in principle, perfect synchronicity escapes us. Relativity dictates that, like a strange syrup, time flows slower on moving trains than in the stations and faster in the mountains than in the valleys. The time for our wristwatch or digital screen is not exactly the same as the time for our head.

Our intuitions are deeply paradoxical. Time heals all wounds, but it is also the great destroyer. Time is relative but also relentless. There is time for every purpose under heaven, but there is never enough.

Scientific American, October 24, 2014. Adaptado.

What time isit? Thatsimple question probably is asked more often today than ever. In our clock‐studded, cell‐phone society, the answer is never more than a glance away, and so we can blissfully partition our daysinto eversmaller incrementsfor ever more tightly scheduled tasks, confident that we will always know it is 7:03 P.M.

Modern scientific revelations about time, however, make the question endlessly frustrating. If we seek a precise knowledge of the time, the elusive infinitesimal of “now” dissolves into a scattering flock of nanoseconds. Bound by the speed of light and the velocity of nerve impulses, our perceptions of the present sketch the world as it was an instant ago—for all that our consciousness pretends otherwise, we can never catch up.

Even in principle, perfect synchronicity escapes us. Relativity dictates that, like a strange syrup, time flows slower on moving trains than in the stations and faster in the mountains than in the valleys. The time for our wristwatch or digital screen is not exactly the same as the time for our head.

Our intuitions are deeply paradoxical. Time heals all wounds, but it is also the great destroyer. Time is relative but also relentless. There is time for every purpose under heaven, but there is never enough.

Scientific American, October 24, 2014. Adaptado.

What time isit? Thatsimple question probably is asked more often today than ever. In our clock‐studded, cell‐phone society, the answer is never more than a glance away, and so we can blissfully partition our daysinto eversmaller incrementsfor ever more tightly scheduled tasks, confident that we will always know it is 7:03 P.M.

Modern scientific revelations about time, however, make the question endlessly frustrating. If we seek a precise knowledge of the time, the elusive infinitesimal of “now” dissolves into a scattering flock of nanoseconds. Bound by the speed of light and the velocity of nerve impulses, our perceptions of the present sketch the world as it was an instant ago—for all that our consciousness pretends otherwise, we can never catch up.

Even in principle, perfect synchronicity escapes us. Relativity dictates that, like a strange syrup, time flows slower on moving trains than in the stations and faster in the mountains than in the valleys. The time for our wristwatch or digital screen is not exactly the same as the time for our head.

Our intuitions are deeply paradoxical. Time heals all wounds, but it is also the great destroyer. Time is relative but also relentless. There is time for every purpose under heaven, but there is never enough.

Scientific American, October 24, 2014. Adaptado.

Genetic Fortune-Telling

One day, babies will get DNA report cards at birth. These

reports will offer predictions about their chances of suffering

a heart attack or cancer, of

getting hooked on tobacco,

and of being smarter than

average.

Though the new DNA tests offer probabilities, not diagnoses, they could greatly benefit medicine. For example, if women at high risk for breast cancer got more mammograms and those at low risk got fewer, those exams might catch more real cancers and set off fewer false alarms. The trouble is, the predictions are far from perfect. What if someone with a low risk score for cancer puts off being screened, and then develops cancer anyway? Polygenic scores are also controversial because they can predict any trait, not only diseases. For instance, they can now forecast about 10 percent of a person’s performance on IQ tests. But how will parents and educators use that information?

(Adaptado de Derek Brahney, Genetic Fortune-Telling. MIT Technology Review, Março/Abril 2018)

De acordo com o texto, um dos riscos do prognóstico

genético dos indivíduos desde o nascimento seria o de

By Edna St. Vincent Millay

Love is not all: It is not meat nor drink Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain; Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink And rise and sink and rise and sink again; Love cannot fill the thickened lung with breath, Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone; Yet many a man is making friends with death Even as I speak, for lack of love alone. It well may be that in a difficult hour, Pinned down by need and moaning for release, Or nagged by want past resolution's power, I might be driven to sell your love for peace, Or trade the memory of this night for food. It may well be. I do not think I would.

(Disponível em https://www.poemhunter.com/. Acessado em 28/05/2018.)

De acordo com o poema

Elena Ferrante

I love my country, but I have no patriotic spirit and no national pride. What’s more, I digest pizza poorly, I eat very little spaghetti, I don’t speak in a loud voice, I don’t gesticulate, I hate all mafias, I don’t exclaim “Mamma mia!” National characteristics are simplifications that should be contested. Being Italian, for me, begins and ends with the fact that I speak and write in the Italian language. Put that way it doesn’t seem like much, but really it’s a lot. A language is a compendium of the history, geography, material and spiritual life, the vices and virtues, not only of those who speak it, but also of those who have spoken it through the centuries. When I say that I’m Italian because I write in Italian, I mean that I’m fully Italian in the only way that I’m willing to attribute to myself a nationality. I don’t like the other ways, especially when they become nationalism, chauvinism, and imperialism.

(Adaptado de Elena Ferrante, ‘Yes, I´m Italian – but I´m not loud, I don´t gesticulate and I´m not good with pizza’, The Guardian, 24/02/2018.)

Transcrevem-se, a seguir, versos de canções brasileiras e de um poema de Vinícius de Moraes. Assinale a alternativa que melhor exemplifica as afirmações de Elena Ferrante.

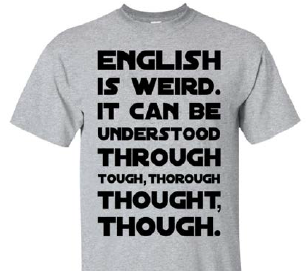

(Adaptado de https://www.teachersloungeshop.com. Acessado em 30/04/2018.)

Os dizeres da camiseta

We raise girls to cater to the fragile

egos of men. We teach girls do shrink

themselves, to make themselves

smaller. We tell girls ‘You can have

ambition, but not too much’. ‘You

should aim to be successful, but not too successful,

otherwise you will threaten the man’. (…) We teach girls

shame – ‘Close your legs, cover yourself!’. We make them

feel as though by being born female, they’re already guilty

of something. And so, girls grow up to be women who

cannot see they have desire. They grow up to be women

who silence themselves. They grow up to be women who

cannot say what they truly think. And they grow up – and

this is the worst thing we do to girls – to be women who

turn pretense into an art form.

We raise girls to cater to the fragile

egos of men. We teach girls do shrink

themselves, to make themselves

smaller. We tell girls ‘You can have

ambition, but not too much’. ‘You

should aim to be successful, but not too successful,

otherwise you will threaten the man’. (…) We teach girls

shame – ‘Close your legs, cover yourself!’. We make them

feel as though by being born female, they’re already guilty

of something. And so, girls grow up to be women who

cannot see they have desire. They grow up to be women

who silence themselves. They grow up to be women who

cannot say what they truly think. And they grow up – and

this is the worst thing we do to girls – to be women who

turn pretense into an art form.

(Adaptado da palestra “We should all be feminists”, 15/07/2009. Disponível em https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hg3umXU_qWc&t=797s. Acessado em 14/05/2018.)

O texto anterior reproduz trechos de uma palestra

proferida pela escritora nigeriana Chimamanda Adichie em

2009. Segundo a autora, o fato de serem criadas para

agradar aos homens faz com que as mulheres

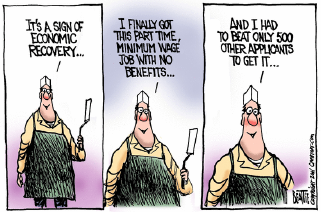

(Disponível em https://www.creators.com/read/bruce-beattie/01/11/70433. Acessado em 18/03/2018.)

Este cartum foi criado pelo norte-americano Bruce Beattie, em 2011. Nele, o cartunista faz uso da ironia para

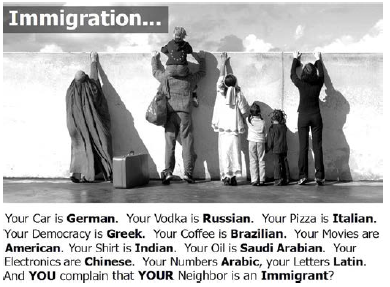

(Adaptado de https://br.pinterest.com. Acessado em 10/06/2018.)

O post anterior aponta

Known simply as M77232917, the figure is arrived at by calculating two to the power of 77,232,917 and subtracting one, leaving a gargantuan string of 23,249,425 digits. The result is nearly one million digits longer than the previous record holder discovered in January 2016. The number belongs to a rare group of so-called Mersenne prime numbers, named after the 17th century French monk Marin Mersenne. Like any prime number, a Mersenne prime is divisible only by itself and one, but is derived by multiplying twos together over and over before taking away one. The previous record-holding number was the 49th Mersenne prime ever found, making the new one the 50th.

(Adaptado de Ian Sample, “Largest prime number discovered: with more than 23m digits”. The Guardian, 04/ 01/2018.)

Considerando as informações contidas no excerto anterior, qual dos números a seguir é um primo de Mersenne?

Touching thermal-paper receipts could extend BPA retention in the body

(Deirdre Lockwood, Touching thermal-paper receipts could extend BPA retention in the body. Chemical & Engineering News, 04/09/2017.)

O texto discorre sobre uma pesquisa cujo objetivo foi

Ancient dreams of intelligent machines: 3,000 years of robots

The French philosopher René Descartes was reputedly fond of automata: they inspired his view that living things were biological machines that function like clockwork. Less known is a strange story that began to circulate after the philosopher’s death in 1650. This centred on Descartes’s daughter Francine, who died of scarlet fever at the age of five.

According to the tale, a distraught Descartes had a clockwork Francine made: a walking, talking simulacrum. When Queen Christina invited the philosopher to Sweden in 1649, he sailed with the automaton concealed in a casket. Suspicious sailors forced the trunk open; when the mechanical child sat up to greet them, the horrified crew threw it overboard.

The story is probably apocryphal. But it sums up the hopes and fears that have been associated with human-like machines for nearly three millennia. Those who build such devices do so in the hope that they will overcome natural limits – in Descartes’s case, death itself. But this very unnaturalness terrifies and repulses others. In our era of advanced robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), those polarized responses persist, with pundits and the public applauding or warning against each advance. Digging into the deep history of intelligent machines, both real and imagined, we see how these attitudes evolved: from fantasies of trusty mechanical helpers to fears that runaway advances in technology might lead to creatures that supersede humanity itself.

(Disponível em: <https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05773-y)

Ancient dreams of intelligent machines: 3,000 years of robots

The French philosopher René Descartes was reputedly fond of automata: they inspired his view that living things were biological machines that function like clockwork. Less known is a strange story that began to circulate after the philosopher’s death in 1650. This centred on Descartes’s daughter Francine, who died of scarlet fever at the age of five.

According to the tale, a distraught Descartes had a clockwork Francine made: a walking, talking simulacrum. When Queen Christina invited the philosopher to Sweden in 1649, he sailed with the automaton concealed in a casket. Suspicious sailors forced the trunk open; when the mechanical child sat up to greet them, the horrified crew threw it overboard.

The story is probably apocryphal. But it sums up the hopes and fears that have been associated with human-like machines for nearly three millennia. Those who build such devices do so in the hope that they will overcome natural limits – in Descartes’s case, death itself. But this very unnaturalness terrifies and repulses others. In our era of advanced robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), those polarized responses persist, with pundits and the public applauding or warning against each advance. Digging into the deep history of intelligent machines, both real and imagined, we see how these attitudes evolved: from fantasies of trusty mechanical helpers to fears that runaway advances in technology might lead to creatures that supersede humanity itself.

(Disponível em: <https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05773-y)