Questões de Vestibular

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 4.863 questões

TEXTO 3:

THIS SIMPLE MIND TRICK CAN INSTANTLY BOOST

YOUR WILLPOWER BY

ELISA ROLAND

A good dose of willpower is often necessary to see any task through, whether it’s sticking to a spending plan or finishing that great American novel.

And if you want to increase that willpower, you just simply have to believe you have it, suggests a new study supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

“What matters most is what we think about our willpower,” leader study author Christopher Napolitano, educational psychology professor at the University of Illinois told the University of Illinois News Bureau. “When we view our willpower as limited, it’s similar to a muscle that gets tired and needs rest. If we believe it is a finite resource, we act that way, feeling exhausted and needing breaks between demanding mental tasks, while people who view their willpower as a limitless resource get energized instead.”

Napolitano and study co-author Veronika Job of the University of Zurich tested the validity of the Implicit Theory of Willpower for Strenuous Mental Activities Scale, a psychological assessment tool. They asked 1,100 Americans and 1,600 Europeans to weigh in on statements such as “After a strenuous mental activity, your energy is depleted, and you must rest to get it refueled again.”

Although there was little difference between men and women overall, Americans were more likely to admit to needing breaks after completing mentally challenging tasks, while European participants became more invigorated to keep going.

Based on the findings, Napolitano suggests that the key to amp up your willpower is to believe that you have an abundant supply of it.

“Your feelings about your willpower affect the way you behave—but these feelings are changeable,” he said. “Changing your beliefs about the nature of your self-control can have positive effects on development, leading to healthier behaviors and perceptions of others.”

Now that you have the drive, make sure you have the other winning attributes all successful people have in common.

Available at: <https://www.rd.com/advice/work-career/trick-boost-willpower/>.

Verifique se as sentenças abaixo são verdadeiras ou falsas de acordo com o texto:

( ) Um novo estudo sugere que a chave para aumentar sua força de vontade é acreditar que você tem uma oferta abundante dela.

( ) Pessoas que acreditam que sua força de vontade é finita não conseguem realizar tarefas mentais mais exigentes.

( ) O estudo revelou que os Americanos eram propensos a admitir a necessidade de pausas após a conclusão de tarefas mentalmente desafiadoras.

( ) Segundo Napolitano, os sentimentos sobre a força de vontade afetam a maneira como um indivíduo se comporta, porém esses sentimentos não são mutáveis.

Assinale a sequência correta:

TEXTO 2:

24 March 2018

Drivers are being temporarily blinded by modern vehicle

headlights, according to an RAC survey.

Two-thirds of drivers say they are "regularly dazzled" by oncoming headlights even though they are dipped, the survey of 2,061 motorists suggests.

And 67% of those said it can take up to fi ve seconds for their sight to clear with a further 10% claiming the eff ect on their eyes lasts up to 10 seconds.

The RAC said advances in headlight technology were causing the problem.

About 15% of those drivers polled said they had nearly suff ered a collision as a result of being dazzled by other drivers using full-beam headlights.

'Unwanted risk'

RAC road safety spokesman Pete Williams said: "The intensity and brightness of some new car headlights is clearly causing diffi culty for other road users.

"Headlight technology has advanced considerably in recent years, but while that may be better for the drivers of those particular vehicles, it is presenting an unwanted, new road safety risk for anyone driving towards them or even trying to pull out at a junction.”

All cars sold for road use in the UK have to be fi tted with headlamps that conform to standards set by the EU in line with the UN's World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations.

A UN working party is currently looking at the issue of headlight glare with its next meeting due to be held at the end of next month.

Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43525525>

TEXTO 2:

24 March 2018

Drivers are being temporarily blinded by modern vehicle

headlights, according to an RAC survey.

Two-thirds of drivers say they are "regularly dazzled" by oncoming headlights even though they are dipped, the survey of 2,061 motorists suggests.

And 67% of those said it can take up to fi ve seconds for their sight to clear with a further 10% claiming the eff ect on their eyes lasts up to 10 seconds.

The RAC said advances in headlight technology were causing the problem.

About 15% of those drivers polled said they had nearly suff ered a collision as a result of being dazzled by other drivers using full-beam headlights.

'Unwanted risk'

RAC road safety spokesman Pete Williams said: "The intensity and brightness of some new car headlights is clearly causing diffi culty for other road users.

"Headlight technology has advanced considerably in recent years, but while that may be better for the drivers of those particular vehicles, it is presenting an unwanted, new road safety risk for anyone driving towards them or even trying to pull out at a junction.”

All cars sold for road use in the UK have to be fi tted with headlamps that conform to standards set by the EU in line with the UN's World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations.

A UN working party is currently looking at the issue of headlight glare with its next meeting due to be held at the end of next month.

Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43525525>

TEXTO 1:

YOUTUBE TO BAN VIDEOS PROMOTING GUN SALES

By NIRAJ CHOKSHI MARCH 22, 2018

YouTube said this week that it would tighten restrictions on some firearm videos, its latest policy announcement since coming under scrutiny after last month’s mass shooting at a high school in Parkland, Fla.

The video-streaming service, which is owned by Google, said it would ban videos that promote either the construction or sale of firearms and their accessories. The new policy, developed with expert advice over the last four months, will go into effect next month, it said.

“While we’ve long prohibited the sale of firearms, we recently notified creators of updates we will be making

around content promoting the sale or manufacture of firearms and their accessories, specifically, items like

ammunition, gatling triggers, and drop-in auto sears,” YouTube said in a statement.

YouTube, which described the move as part of “regular changes” to policy, notified users in a Monday forum post. The company had previously banned videos showing how to make firearms discharge faster, a technique used by the gunman who killed 58 people in Las Vegas last fall.

The announcement comes days before planned student-led protests against gun violence on Saturday. It was met with frustration from gun rights advocates.

“Much like Facebook, YouTube now acts as a virtual public square,” the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a private group representing gun makers, said in a statement. “The exercise of what amounts to censorship, then, can legitimately be viewed as the stifling of commercial free speech, which has constitutional protection. Such actions also impinge on the Second Amendment.”

The policy shift comes as YouTube and other technology platforms face increased scrutiny after the Parkland shooting, in which 17 people were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

Days after that massacre, a video promoting a baseless conspiracy about a shooting survivor became the top-trending video on YouTube, prompting a crackdown on such videos. YouTube’s chief executive also said that the platform planned to fight misinformation by working in partnership with Wikipedia, the nonprofit userrun online encyclopedia. But Wikipedia said it knew nothing about that plan.

Other businesses have also made changes amid growing pressure following the Parkland attack.

Dick’s Sporting Goods, Walmart and Kroger all raised the age limit for firearm purchases to 21. The retail chains REI and Mountain Equipment Co-op suspended orders of some popular products because the company that owns those brands, Vista Outdoor, also manufactures assault-style rifles.

In 2016, Facebook announced a ban on private gun sales on its flagship website as well as on Instagram, the photo-sharing social network it owns. Anti-gun activists have complained that sellers still found ways around Facebook’s ban.

Available at:<https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/22/business/youtube-gun-ban.h...m_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=5&pgtype=sectionfront>

Stephen Hawking

Dies at 76; His Mind

Roamed the Cosmos

A physicist and best-selling author, Dr. Hawking did not allow his physical limitations to hinder his quest to answer “the big question: Where did the universe come from?”

Stephen W. Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist

and best-selling author who roamed the cosmos from a

wheelchair, pondering the nature of gravity and the origin

of the universe and becoming an emblem of human

determination and curiosity, died early Wednesday at his

home in Cambridge, England. He was 76.

His death was confirmed by a spokesman for Cambridge

University.

“Not since Albert Einstein has a scientist so captured the public imagination and endeared himself to tens of millions of people around the world” Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Hawking did that largely through his book “A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes,” published in 1988. It has sold more than 10 million copies and inspired a documentary film by Errol Morris. The 2014 film about his life, “The Theory of Everything” was nominated for several Academy Awards and Eddie Redmayne, who played Dr. Hawking, won the Oscar for best actor.

Scientifically, Dr. Hawking will be best remembered for a discovery so strange that it might be expressed in the form of a Zen koan: When is a black hole not black? When it explodes.

What is equally amazing is that he had a career at all. As a graduate student in 1963, he learned he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a neuromuscular wasting disease also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was given only a few years to live.

The disease reduced his bodily control to the flexing of a finger and voluntary eye movements but left his mental faculties untouched.

He went on to become his generation’s leader in exploring gravity and the properties of black holes, the bottomless gravitational pits so deep and dense that not even light can escape them.

That work led to a turning point in modern physics, playing itself out in the closing months of 1973 on the walls of his brain when Dr. Hawking set out to apply quantum theory, the weird laws that govern subatomic reality, to black holes. In a long and daunting calculation, Dr. Hawking discovered to his befuddlement that black holes — those mythological avatars of cosmic doom — were not really black at all. In fact, he found, they would eventually fizzle, leaking radiation and particles, and finally explode and disappear over the eons. (Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/obituaries/stephenhawking-dead.html. Adapted)

Stephen Hawking

Dies at 76; His Mind

Roamed the Cosmos

A physicist and best-selling author, Dr. Hawking did not allow his physical limitations to hinder his quest to answer “the big question: Where did the universe come from?”

Stephen W. Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist

and best-selling author who roamed the cosmos from a

wheelchair, pondering the nature of gravity and the origin

of the universe and becoming an emblem of human

determination and curiosity, died early Wednesday at his

home in Cambridge, England. He was 76.

His death was confirmed by a spokesman for Cambridge

University.

“Not since Albert Einstein has a scientist so captured the public imagination and endeared himself to tens of millions of people around the world” Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Hawking did that largely through his book “A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes,” published in 1988. It has sold more than 10 million copies and inspired a documentary film by Errol Morris. The 2014 film about his life, “The Theory of Everything” was nominated for several Academy Awards and Eddie Redmayne, who played Dr. Hawking, won the Oscar for best actor.

Scientifically, Dr. Hawking will be best remembered for a discovery so strange that it might be expressed in the form of a Zen koan: When is a black hole not black? When it explodes.

What is equally amazing is that he had a career at all. As a graduate student in 1963, he learned he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a neuromuscular wasting disease also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was given only a few years to live.

The disease reduced his bodily control to the flexing of a finger and voluntary eye movements but left his mental faculties untouched.

He went on to become his generation’s leader in exploring gravity and the properties of black holes, the bottomless gravitational pits so deep and dense that not even light can escape them.

That work led to a turning point in modern physics, playing itself out in the closing months of 1973 on the walls of his brain when Dr. Hawking set out to apply quantum theory, the weird laws that govern subatomic reality, to black holes. In a long and daunting calculation, Dr. Hawking discovered to his befuddlement that black holes — those mythological avatars of cosmic doom — were not really black at all. In fact, he found, they would eventually fizzle, leaking radiation and particles, and finally explode and disappear over the eons. (Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/obituaries/stephenhawking-dead.html. Adapted)

Leia as proposições abaixo. Marque a opção que corresponda à sequência de alternativas CORRETAS.

I. Stephen Hawking nasceu por volta de 1942.

II. “Spokesman” pode ser traduzido como “porta-voz”.

III. Hawking foi o único teórico da sua geração a falar da gravidade e das propriedades do buraco negro.

IV. Os buracos negros podem eventualmente vazar radiação, partículas, explodir e por fim desaparecerem.

Stephen Hawking

Dies at 76; His Mind

Roamed the Cosmos

A physicist and best-selling author, Dr. Hawking did not allow his physical limitations to hinder his quest to answer “the big question: Where did the universe come from?”

Stephen W. Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist

and best-selling author who roamed the cosmos from a

wheelchair, pondering the nature of gravity and the origin

of the universe and becoming an emblem of human

determination and curiosity, died early Wednesday at his

home in Cambridge, England. He was 76.

His death was confirmed by a spokesman for Cambridge

University.

“Not since Albert Einstein has a scientist so captured the public imagination and endeared himself to tens of millions of people around the world” Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at the City University of New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Hawking did that largely through his book “A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes,” published in 1988. It has sold more than 10 million copies and inspired a documentary film by Errol Morris. The 2014 film about his life, “The Theory of Everything” was nominated for several Academy Awards and Eddie Redmayne, who played Dr. Hawking, won the Oscar for best actor.

Scientifically, Dr. Hawking will be best remembered for a discovery so strange that it might be expressed in the form of a Zen koan: When is a black hole not black? When it explodes.

What is equally amazing is that he had a career at all. As a graduate student in 1963, he learned he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a neuromuscular wasting disease also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was given only a few years to live.

The disease reduced his bodily control to the flexing of a finger and voluntary eye movements but left his mental faculties untouched.

He went on to become his generation’s leader in exploring gravity and the properties of black holes, the bottomless gravitational pits so deep and dense that not even light can escape them.

That work led to a turning point in modern physics, playing itself out in the closing months of 1973 on the walls of his brain when Dr. Hawking set out to apply quantum theory, the weird laws that govern subatomic reality, to black holes. In a long and daunting calculation, Dr. Hawking discovered to his befuddlement that black holes — those mythological avatars of cosmic doom — were not really black at all. In fact, he found, they would eventually fizzle, leaking radiation and particles, and finally explode and disappear over the eons. (Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/obituaries/stephenhawking-dead.html. Adapted)

TEXT 2

The first step in establishing a cyber ethical culture is to ask the really tough questions, the answer to which may be politically incorrect. HR (Human resources), legal, security and top management need to work together to set the tone they wish to flow through gaming; other times off-site meetings will work.

The second step is to include cyber ethical components in corporate security awareness campaigns to keep employees clued in.

The last but most important step is to be ready to make changes rapidly when cyber ethics becomes a component of information security efforts. We cannot predict how they will change tomorrow or next year – but we need to be prepared.

(MARINOTTO, Demóstene. Reading on Info Tech (Inglês para Informática). São Paulo, Novatec, 2007.)

TEXT 1

These days, when our slow recovery from recession seems like a full-employment program for pessimistic pundits, it’s great to have a new book from Chris Anderson, an indefatigable cheerleader for the unlimited potential of the digital economy. Anderson, the departing editor in chief of Wired magazine, has already written two important books exploring the impact of the Web on commerce. In “The Long Tail,” he argued that companies like Amazon that faced distribution challenges arising from having large quantities of the same kind of product would thrive by “selling less of more.” Corporations didn’t have to chase blockbusters if they had a mass of small sales. In “Free: The Future of a Radical Price,” he argued that giving stuff away to attract a multitude of users might be the best way eventually to make money from loyal customers. Anderson has also helped found a Web site, Geekdad, and an aerial robotics company. From his vantage point, in the future more and more people can get involved in making things they really enjoy and can connect with others who share their passions and their products. These connections, he claims, are creating a new Industrial Revolution.

In a 2010 Wired article entitled “In the Next Industrial Revolution, Atoms Are the New Bits,” Anderson described how the massive changes in our relations with information have altered how we relate to things. Now that the power of information-sharing has been unleashed through technology and social networks, makers are able to collaborate on design and production in ways that facilitate the connection of producers to markets. By sharing information “bits” in a creative commons, entrepreneurs are making new things (reshaping “atoms”) more cheaply and quickly. The new manufacturing is a powerful economic force not because any one business becomes gigantic, but because technology makes it possible for tens of thousands of businesses to find their customers, to form their communities.

Anderson begins his new book, “Makers,” with the story of his grandfather Fred Hauser, who invented a sprinkler system. He licensed his invention to a company that turned ideas into things that could be built and sold. Although Hauser loved translating ideas into things, he needed a company with resources to make enough of his sprinklers to turn a profit. Inventing and making were separate. With the advent of the personal computer and of sophisticated but user-friendly design tools, that separation has become increasingly irrelevant. As a child, Anderson loved making things with his grandfather, and he still loves creating new stuff and getting it into the marketplace. “Makers” describes how today technology has liberated the inventor from a dependence on the big manufacturer. “The beauty of the Web is that it democratized the tools both of invention and production,” Anderson writes. “We are all designers now. It’s time to get good at it.”

(Fragment from “Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by

Chris Anderson”, by Michael S. Roth. Online since 24

November 2012.

URL:https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/makers-thenew-industrial-revolution)

TEXT 1

These days, when our slow recovery from recession seems like a full-employment program for pessimistic pundits, it’s great to have a new book from Chris Anderson, an indefatigable cheerleader for the unlimited potential of the digital economy. Anderson, the departing editor in chief of Wired magazine, has already written two important books exploring the impact of the Web on commerce. In “The Long Tail,” he argued that companies like Amazon that faced distribution challenges arising from having large quantities of the same kind of product would thrive by “selling less of more.” Corporations didn’t have to chase blockbusters if they had a mass of small sales. In “Free: The Future of a Radical Price,” he argued that giving stuff away to attract a multitude of users might be the best way eventually to make money from loyal customers. Anderson has also helped found a Web site, Geekdad, and an aerial robotics company. From his vantage point, in the future more and more people can get involved in making things they really enjoy and can connect with others who share their passions and their products. These connections, he claims, are creating a new Industrial Revolution.

In a 2010 Wired article entitled “In the Next Industrial Revolution, Atoms Are the New Bits,” Anderson described how the massive changes in our relations with information have altered how we relate to things. Now that the power of information-sharing has been unleashed through technology and social networks, makers are able to collaborate on design and production in ways that facilitate the connection of producers to markets. By sharing information “bits” in a creative commons, entrepreneurs are making new things (reshaping “atoms”) more cheaply and quickly. The new manufacturing is a powerful economic force not because any one business becomes gigantic, but because technology makes it possible for tens of thousands of businesses to find their customers, to form their communities.

Anderson begins his new book, “Makers,” with the story of his grandfather Fred Hauser, who invented a sprinkler system. He licensed his invention to a company that turned ideas into things that could be built and sold. Although Hauser loved translating ideas into things, he needed a company with resources to make enough of his sprinklers to turn a profit. Inventing and making were separate. With the advent of the personal computer and of sophisticated but user-friendly design tools, that separation has become increasingly irrelevant. As a child, Anderson loved making things with his grandfather, and he still loves creating new stuff and getting it into the marketplace. “Makers” describes how today technology has liberated the inventor from a dependence on the big manufacturer. “The beauty of the Web is that it democratized the tools both of invention and production,” Anderson writes. “We are all designers now. It’s time to get good at it.”

(Fragment from “Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by

Chris Anderson”, by Michael S. Roth. Online since 24

November 2012.

URL:https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/makers-thenew-industrial-revolution)

TEXT 1

These days, when our slow recovery from recession seems like a full-employment program for pessimistic pundits, it’s great to have a new book from Chris Anderson, an indefatigable cheerleader for the unlimited potential of the digital economy. Anderson, the departing editor in chief of Wired magazine, has already written two important books exploring the impact of the Web on commerce. In “The Long Tail,” he argued that companies like Amazon that faced distribution challenges arising from having large quantities of the same kind of product would thrive by “selling less of more.” Corporations didn’t have to chase blockbusters if they had a mass of small sales. In “Free: The Future of a Radical Price,” he argued that giving stuff away to attract a multitude of users might be the best way eventually to make money from loyal customers. Anderson has also helped found a Web site, Geekdad, and an aerial robotics company. From his vantage point, in the future more and more people can get involved in making things they really enjoy and can connect with others who share their passions and their products. These connections, he claims, are creating a new Industrial Revolution.

In a 2010 Wired article entitled “In the Next Industrial Revolution, Atoms Are the New Bits,” Anderson described how the massive changes in our relations with information have altered how we relate to things. Now that the power of information-sharing has been unleashed through technology and social networks, makers are able to collaborate on design and production in ways that facilitate the connection of producers to markets. By sharing information “bits” in a creative commons, entrepreneurs are making new things (reshaping “atoms”) more cheaply and quickly. The new manufacturing is a powerful economic force not because any one business becomes gigantic, but because technology makes it possible for tens of thousands of businesses to find their customers, to form their communities.

Anderson begins his new book, “Makers,” with the story of his grandfather Fred Hauser, who invented a sprinkler system. He licensed his invention to a company that turned ideas into things that could be built and sold. Although Hauser loved translating ideas into things, he needed a company with resources to make enough of his sprinklers to turn a profit. Inventing and making were separate. With the advent of the personal computer and of sophisticated but user-friendly design tools, that separation has become increasingly irrelevant. As a child, Anderson loved making things with his grandfather, and he still loves creating new stuff and getting it into the marketplace. “Makers” describes how today technology has liberated the inventor from a dependence on the big manufacturer. “The beauty of the Web is that it democratized the tools both of invention and production,” Anderson writes. “We are all designers now. It’s time to get good at it.”

(Fragment from “Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by

Chris Anderson”, by Michael S. Roth. Online since 24

November 2012.

URL:https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/makers-thenew-industrial-revolution)

TEXT 1

These days, when our slow recovery from recession seems like a full-employment program for pessimistic pundits, it’s great to have a new book from Chris Anderson, an indefatigable cheerleader for the unlimited potential of the digital economy. Anderson, the departing editor in chief of Wired magazine, has already written two important books exploring the impact of the Web on commerce. In “The Long Tail,” he argued that companies like Amazon that faced distribution challenges arising from having large quantities of the same kind of product would thrive by “selling less of more.” Corporations didn’t have to chase blockbusters if they had a mass of small sales. In “Free: The Future of a Radical Price,” he argued that giving stuff away to attract a multitude of users might be the best way eventually to make money from loyal customers. Anderson has also helped found a Web site, Geekdad, and an aerial robotics company. From his vantage point, in the future more and more people can get involved in making things they really enjoy and can connect with others who share their passions and their products. These connections, he claims, are creating a new Industrial Revolution.

In a 2010 Wired article entitled “In the Next Industrial Revolution, Atoms Are the New Bits,” Anderson described how the massive changes in our relations with information have altered how we relate to things. Now that the power of information-sharing has been unleashed through technology and social networks, makers are able to collaborate on design and production in ways that facilitate the connection of producers to markets. By sharing information “bits” in a creative commons, entrepreneurs are making new things (reshaping “atoms”) more cheaply and quickly. The new manufacturing is a powerful economic force not because any one business becomes gigantic, but because technology makes it possible for tens of thousands of businesses to find their customers, to form their communities.

Anderson begins his new book, “Makers,” with the story of his grandfather Fred Hauser, who invented a sprinkler system. He licensed his invention to a company that turned ideas into things that could be built and sold. Although Hauser loved translating ideas into things, he needed a company with resources to make enough of his sprinklers to turn a profit. Inventing and making were separate. With the advent of the personal computer and of sophisticated but user-friendly design tools, that separation has become increasingly irrelevant. As a child, Anderson loved making things with his grandfather, and he still loves creating new stuff and getting it into the marketplace. “Makers” describes how today technology has liberated the inventor from a dependence on the big manufacturer. “The beauty of the Web is that it democratized the tools both of invention and production,” Anderson writes. “We are all designers now. It’s time to get good at it.”

(Fragment from “Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by

Chris Anderson”, by Michael S. Roth. Online since 24

November 2012.

URL:https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/makers-thenew-industrial-revolution)

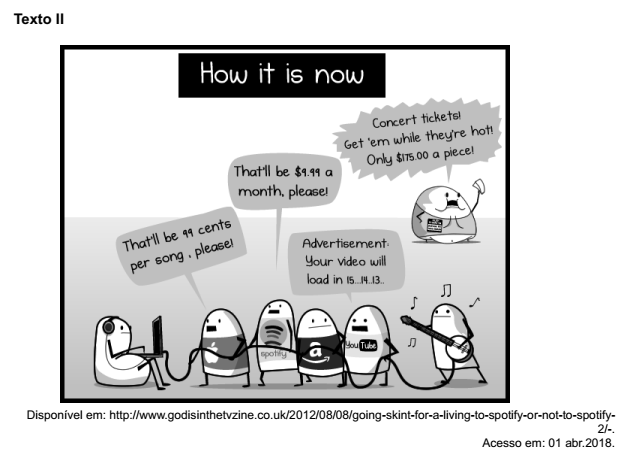

Shares in the music streaming firm Spotify will be publicly traded for the first time when the firm debuts on the New York market.

The flotation marks a turning point for the firm that after 12 years has not yet made a profit. Spotify's listing, which could value it at $20billion (£14 billion), is unconventional: it is not issuing any new shares. Instead, shares held by the firm's private investors will be made available.

What was once an small upstart Swedish music platform, has grown rapidly in recent years, adding millions of users to its free-to-use ad-funded service, and converting many of them to its more lucrative subscription service. It's used in 61 countries, has 159 million active users and a library of 35 million songs. They developed the platform in 2006 as a response to the growing piracy problem the music industry was facing. It is now the global leader among music streaming companies, boasting 71 million paying customers, twice as many as runner-up Apple.

What Spotify must do to survive? So far costs and fees to recording companies for the rights to play their music, have exceeded Spotify's revenues. And some analysts predict the listing will speed-up Spotify's race towards profitability. "When that's done we'll see a bit of a shift in strategy and direction." says Mark Mulligan at MIDia Research. The firm made a commitment to investors who backed it as the company was growing, that they would be given the chance to cash in their investment. The streaming giant has filed for paperwork to start trading its shares publicly on the New York Stock Exchange.

What will Spotify look like in the future? So what will change? "So far they've been treading a very fine line between being the dramatic new future of the music business but simultaneously being the biggest friend of the old music industry by giving record labels a platform to build out of decline," says Mr Mulligan.

"To go to the next phase [Spotify] will have to stop being so friendly to the record companies." More than half of Spotify's revenue goes directly to the record companies. Chris Hayes expects Spotify to evolve. "I think over time they're going to have to diversify their offering." he says, helping to set them apart from a sea of rival streaming services. They have already moved into podcasts and producing original music. They may well start to offer more original content like Taylor Swift's recent video which was only made available on the platform, says Chris Hayes.

So can Spotify make money? The firm's first operating profit (not including debt financing) is on the horizon for 2019 based on current trends, according to Mr Hayes. "The strategy has always been the free tier, but it is a funnel through which to persuade free users to upgrade to the subscription tier which is lucrative.

"As long as subscriptions continue to grow it should eventually become profitable. "Spotify's rivals are the biggest companies in the world with bottomless pockets," he says, and they are using music as a way to sell their core products, not as a business proposition in itself.

Apple, Amazon and Google are also in the streaming game and - unlike Spotify - all sell devices on which consumers can listen to music. And while Spotify has signed deals with all the "big three" record labels - Warner, Universal and Sony - it is the music executives that still hold the bargaining chips.

Adapted from: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-43613398. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2018.

Após a leitura do texto I, “Spotify braces for $20billion US share market listing”, e da charge

acima, marque a alternativa INCORRETA:

Shares in the music streaming firm Spotify will be publicly traded for the first time when the firm debuts on the New York market.

The flotation marks a turning point for the firm that after 12 years has not yet made a profit. Spotify's listing, which could value it at $20billion (£14 billion), is unconventional: it is not issuing any new shares. Instead, shares held by the firm's private investors will be made available.

What was once an small upstart Swedish music platform, has grown rapidly in recent years, adding millions of users to its free-to-use ad-funded service, and converting many of them to its more lucrative subscription service. It's used in 61 countries, has 159 million active users and a library of 35 million songs. They developed the platform in 2006 as a response to the growing piracy problem the music industry was facing. It is now the global leader among music streaming companies, boasting 71 million paying customers, twice as many as runner-up Apple.

What Spotify must do to survive? So far costs and fees to recording companies for the rights to play their music, have exceeded Spotify's revenues. And some analysts predict the listing will speed-up Spotify's race towards profitability. "When that's done we'll see a bit of a shift in strategy and direction." says Mark Mulligan at MIDia Research. The firm made a commitment to investors who backed it as the company was growing, that they would be given the chance to cash in their investment. The streaming giant has filed for paperwork to start trading its shares publicly on the New York Stock Exchange.

What will Spotify look like in the future? So what will change? "So far they've been treading a very fine line between being the dramatic new future of the music business but simultaneously being the biggest friend of the old music industry by giving record labels a platform to build out of decline," says Mr Mulligan.

"To go to the next phase [Spotify] will have to stop being so friendly to the record companies." More than half of Spotify's revenue goes directly to the record companies. Chris Hayes expects Spotify to evolve. "I think over time they're going to have to diversify their offering." he says, helping to set them apart from a sea of rival streaming services. They have already moved into podcasts and producing original music. They may well start to offer more original content like Taylor Swift's recent video which was only made available on the platform, says Chris Hayes.

So can Spotify make money? The firm's first operating profit (not including debt financing) is on the horizon for 2019 based on current trends, according to Mr Hayes. "The strategy has always been the free tier, but it is a funnel through which to persuade free users to upgrade to the subscription tier which is lucrative.

"As long as subscriptions continue to grow it should eventually become profitable. "Spotify's rivals are the biggest companies in the world with bottomless pockets," he says, and they are using music as a way to sell their core products, not as a business proposition in itself.

Apple, Amazon and Google are also in the streaming game and - unlike Spotify - all sell devices on which consumers can listen to music. And while Spotify has signed deals with all the "big three" record labels - Warner, Universal and Sony - it is the music executives that still hold the bargaining chips.

Adapted from: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-43613398. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2018.

Shares in the music streaming firm Spotify will be publicly traded for the first time when the firm debuts on the New York market.

The flotation marks a turning point for the firm that after 12 years has not yet made a profit. Spotify's listing, which could value it at $20billion (£14 billion), is unconventional: it is not issuing any new shares. Instead, shares held by the firm's private investors will be made available.

What was once an small upstart Swedish music platform, has grown rapidly in recent years, adding millions of users to its free-to-use ad-funded service, and converting many of them to its more lucrative subscription service. It's used in 61 countries, has 159 million active users and a library of 35 million songs. They developed the platform in 2006 as a response to the growing piracy problem the music industry was facing. It is now the global leader among music streaming companies, boasting 71 million paying customers, twice as many as runner-up Apple.

What Spotify must do to survive? So far costs and fees to recording companies for the rights to play their music, have exceeded Spotify's revenues. And some analysts predict the listing will speed-up Spotify's race towards profitability. "When that's done we'll see a bit of a shift in strategy and direction." says Mark Mulligan at MIDia Research. The firm made a commitment to investors who backed it as the company was growing, that they would be given the chance to cash in their investment. The streaming giant has filed for paperwork to start trading its shares publicly on the New York Stock Exchange.

What will Spotify look like in the future? So what will change? "So far they've been treading a very fine line between being the dramatic new future of the music business but simultaneously being the biggest friend of the old music industry by giving record labels a platform to build out of decline," says Mr Mulligan.

"To go to the next phase [Spotify] will have to stop being so friendly to the record companies." More than half of Spotify's revenue goes directly to the record companies. Chris Hayes expects Spotify to evolve. "I think over time they're going to have to diversify their offering." he says, helping to set them apart from a sea of rival streaming services. They have already moved into podcasts and producing original music. They may well start to offer more original content like Taylor Swift's recent video which was only made available on the platform, says Chris Hayes.

So can Spotify make money? The firm's first operating profit (not including debt financing) is on the horizon for 2019 based on current trends, according to Mr Hayes. "The strategy has always been the free tier, but it is a funnel through which to persuade free users to upgrade to the subscription tier which is lucrative.

"As long as subscriptions continue to grow it should eventually become profitable. "Spotify's rivals are the biggest companies in the world with bottomless pockets," he says, and they are using music as a way to sell their core products, not as a business proposition in itself.

Apple, Amazon and Google are also in the streaming game and - unlike Spotify - all sell devices on which consumers can listen to music. And while Spotify has signed deals with all the "big three" record labels - Warner, Universal and Sony - it is the music executives that still hold the bargaining chips.

Adapted from: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-43613398. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2018.

Shares in the music streaming firm Spotify will be publicly traded for the first time when the firm debuts on the New York market.

The flotation marks a turning point for the firm that after 12 years has not yet made a profit. Spotify's listing, which could value it at $20billion (£14 billion), is unconventional: it is not issuing any new shares. Instead, shares held by the firm's private investors will be made available.

What was once an small upstart Swedish music platform, has grown rapidly in recent years, adding millions of users to its free-to-use ad-funded service, and converting many of them to its more lucrative subscription service. It's used in 61 countries, has 159 million active users and a library of 35 million songs. They developed the platform in 2006 as a response to the growing piracy problem the music industry was facing. It is now the global leader among music streaming companies, boasting 71 million paying customers, twice as many as runner-up Apple.

What Spotify must do to survive? So far costs and fees to recording companies for the rights to play their music, have exceeded Spotify's revenues. And some analysts predict the listing will speed-up Spotify's race towards profitability. "When that's done we'll see a bit of a shift in strategy and direction." says Mark Mulligan at MIDia Research. The firm made a commitment to investors who backed it as the company was growing, that they would be given the chance to cash in their investment. The streaming giant has filed for paperwork to start trading its shares publicly on the New York Stock Exchange.

What will Spotify look like in the future? So what will change? "So far they've been treading a very fine line between being the dramatic new future of the music business but simultaneously being the biggest friend of the old music industry by giving record labels a platform to build out of decline," says Mr Mulligan.

"To go to the next phase [Spotify] will have to stop being so friendly to the record companies." More than half of Spotify's revenue goes directly to the record companies. Chris Hayes expects Spotify to evolve. "I think over time they're going to have to diversify their offering." he says, helping to set them apart from a sea of rival streaming services. They have already moved into podcasts and producing original music. They may well start to offer more original content like Taylor Swift's recent video which was only made available on the platform, says Chris Hayes.

So can Spotify make money? The firm's first operating profit (not including debt financing) is on the horizon for 2019 based on current trends, according to Mr Hayes. "The strategy has always been the free tier, but it is a funnel through which to persuade free users to upgrade to the subscription tier which is lucrative.

"As long as subscriptions continue to grow it should eventually become profitable. "Spotify's rivals are the biggest companies in the world with bottomless pockets," he says, and they are using music as a way to sell their core products, not as a business proposition in itself.

Apple, Amazon and Google are also in the streaming game and - unlike Spotify - all sell devices on which consumers can listen to music. And while Spotify has signed deals with all the "big three" record labels - Warner, Universal and Sony - it is the music executives that still hold the bargaining chips.

Adapted from: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-43613398. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2018.