Questões de Vestibular Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 6.020 questões

Technology isn’t working

The digital revolution has yet to fulfil its promise of higher productivity and better jobs

If there is a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

Technology isn’t working

The digital revolution has yet to fulfil its promise of higher productivity and better jobs

If there is a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

Technology isn’t working

The digital revolution has yet to fulfil its promise of higher productivity and better jobs

If there is a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

Technology isn’t working

The digital revolution has yet to fulfil its promise of higher productivity and better jobs

If there is a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

Technology isn’t working

The digital revolution has yet to fulfil its promise of higher productivity and better jobs

If there is a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

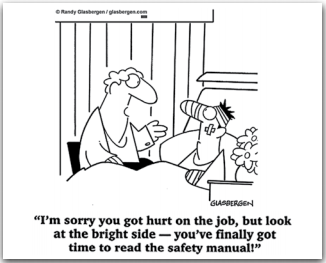

Considere o cartum.

<http://tinyurl.com/kl3oyrm>Acesso em: 16.03.2015.

Learn ‘n’ go

How quickly can people learn new skills?

Jan 25th 2014 – from the print edition

In 2012, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee took a ride in one of Google’s driverless cars. The car’s performance, they report, was flawless, boring and, above all, “weird”. Only a few years earlier, “We were sure that computers would not be able to drive cars.” Only humans, they thought, could make sense of the countless, shifting patterns of driving a car – with oncoming1 traffic, changing lights and wayward2 jaywalkers3 .

Machines have mastered driving. And not just driving. In ways that are only now becoming apparent, the authors argue, machines can forecast home prices, design beer bottles, teach at universities, grade exams and do countless other things better and more cheaply than humans. (…)

This will have one principal good consequence, and one bad. The good is bounty4 . Households will spend less on groceries, utilities and clothing; the deaf will be able to hear, the blind to see. The bad is spread5 . The gap is growing between the lucky few whose abilities and skills are enhanced6 by technology, and the far more numerous middle-skilled people competing for the remaining7 jobs that machines cannot do, such as folding towels and waiting at tables. (…) People should develop skills that complement, rather than compete with computers, such as idea generation and complex communication. (…)